Researchers Grow Vocal Cord Tissue That Can 'Talk'

Researchers have grown vocal cord tissue in the lab, and it works — the tissue was able to produce sound when it was transplanted into intact voice boxes from animals, according to a new study.

This tissue engineering technique could one day be used to restore the voices of patients who have certain voice disorders that are otherwise untreatable, the researchers said.

However, more research is needed before the new technique could be brought to an actual clinical trial in humans, the researchers said.

"This is years away from trial just because of reality of the regulatory requirements," said study author Nathan Welham, a speech-language pathologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

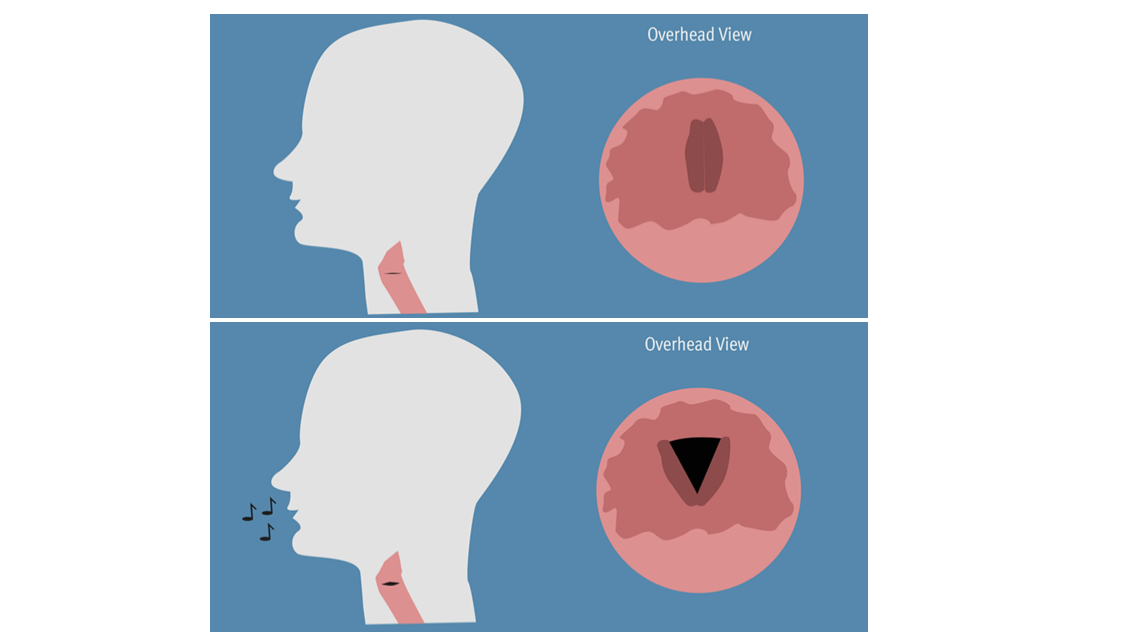

Vocal cords consist of two flexible bands of muscle that are lined with a specialized tissue, called mucosa, which vibrates as air moves over the cords, generating the voice.

When mucosa is injured, it scars and stiffens, which may lead to the loss of a person's voice. Some existing treatments, such as collagen injections, can partially fix the damage, but work only as a short-term measure, the researchers said. Moreover, many of these treatments don't fix the issue of sound output, Welham told Live Science.

"This thing that we have been working on is more a complete replacement of a tissue in those situations where we feel that none of the things on the table are really going to do it here," Welham said. [5 Things a Person's Voice Can Tell You]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For the study, the researchers first collected vocal cord tissue from four people who had their larynges removed for unrelated reasons, and from one human cadaver. The scientists isolated, purified and grew cells from the mucosa in a special 3D culture that closely resembles conditions in the body.

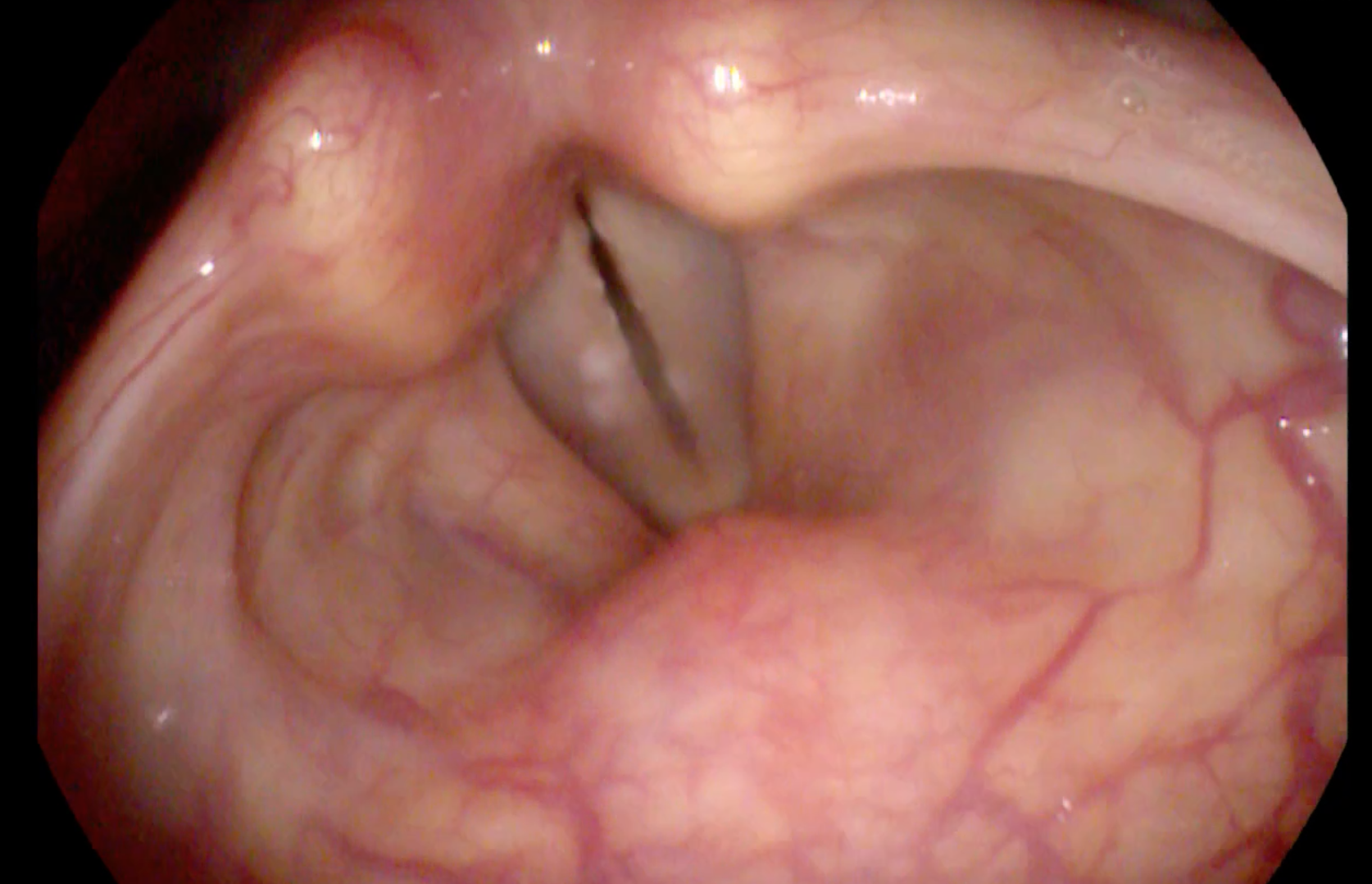

In about two weeks, the cells grew together and formed a tissue that "felt like vocal cord tissue," Welham said in a statement. The viscosity and elasticity of the tissue were similar to the viscosity and elasticity of normal tissue, further tests showed.

To see if the engineered vocal cord tissue could generate sound, the investigators transplanted the tissue into larynges that had been taken from dogs, which are anatomically similar to human larynges. The researchers then attached these larynges to artificial windpipes, and blew humidified air through them.

When the air reached the engineered tissue, the tissue vibrated and generated sound, much like the normal vocal cord tissue normally would.

The sound that the engineered tissue produced was "humanlike," Welham said.

The researchers also looked at whether the engineered vocal cord tissue would be rejected or accepted by mice that had been engineered to have humanlike immune systems. They found that the tissue was well tolerated by the mice and the animals had normal life spans after the transplants.

There was, however, one aspect of the engineered tissue that was inferior to the real tissue: The engineered tissue had a fiber structure that was less complex than the typical fiber structure of normal adult tissue. However, this is not surprising, because vocal cord tissue normally takes time to mature, the researchers said. The development of real human vocal cord tissue is not complete until a person is about 13 years old, they said.

The new study was published today (Nov. 18) in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Follow Agata Blaszczak-Boxe on Twitter. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.