6 Archaeological Forgeries That Could Have Changed History

When a museum acquires a large collection of donated antiquities it is not unusual for curators to find that at least a few of them are fake. While the forgery of artifacts is commonplace there are some forgeries that have become extremely famous, often because their authenticity would have had history-changing results. From crystal skulls claimed to be from the lost city of Atlantis (or aliens) to a runestone said to have been carved by Vikings and even a "missing link" hoax, here are six artifacts, widely believed to be forgeries, which could have changed history.

Donation of Constantine

A forged document, the Donation of Constantine has been copied and recopied since the eighth century. The original is lost but the documents that survive today claim that Roman emperor Constantine I gave Pope Sylvester I, and all of his successors, ultimate authority over lands controlled by the Roman Empire. "We-giving over to the oft-mentioned most blessed pontiff, our father Sylvester the universal pope, as well our palace, as has been said, as also the city of Rome and all the provinces, districts and cities of Italy or of the western regions; and relinquishing them, by our inviolable gift, to the power and sway of himself or the pontiffs his successors-do decree," the Latin document says (translation by Ernest F. Henderson).

When exactly the forgery was created is a matter of debate. But, during the Middle Ages, it was used as evidence that the pope held authority over the rulers of Europe, aiding the pope in political negotiations. In the 15th century Italian scholar Lorenzo Valla denounced the document, publishing a lengthy discourse on why it is a forgery.

Valla knew that he was running a risk in doing so. "How they will rage against me, and if opportunity is afforded how eagerly and how quickly they will drag me to punishment!" he wrote at the start of his book (translation by Christopher B. Coleman). However he found support from rulers in Europe who were tired of the pope using the document as a reason to interfere in their affairs.

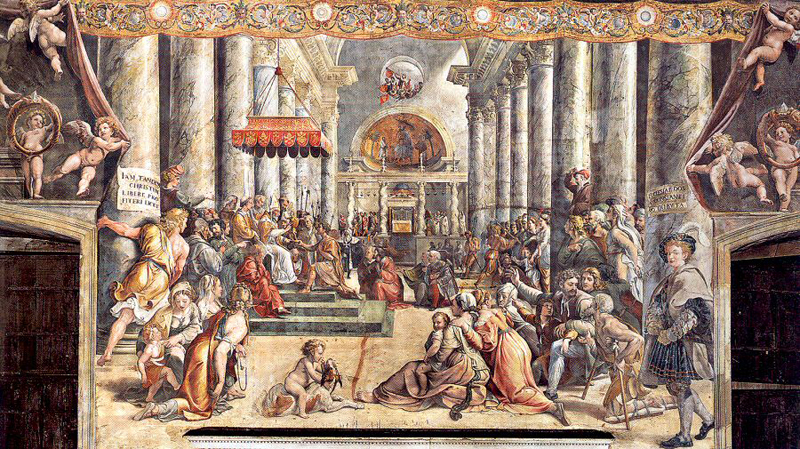

The painting, drawn in the 1520s by an artist working in Raphael's workshop (not necessarily Raphael himself), is based on the forgery and depicts Constantine giving all his lands to Pope Sylvester. The event never took place. The painting is located in Vatican City. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 1912 Arthur Smith Woodward, a paleontologist at the Natural History Museum in London, and Charles Dawson, an amateur antiquarian, reported the discovery of a new species of early human at Piltdown in England. They believed the early human, which was named Eoanthropus dawsoni, could date back 1 million years.

At the time it was uncertain if early humans lived in Britain 1 million years ago and this discovery would have provided proof of it.

The findings drew skepticism, and in time, Eoanthropus dawsoni was revealed to be nothing more than a mix of orangutan and modern human bones. The discovery drew a great amount of publicity. The question of who did it and why is still uncertain; a new investigation by Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum and colleagues is now underway to try to find answers.

Ironically modern-day archaeologists have found evidence of early humans in Britain. When it was that the first humans walked the British Isles is still uncertain, but it could well have been more than 1 million years ago.

This painting depicts a group of scientists peering over the bones. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia.)

Kensington runestone

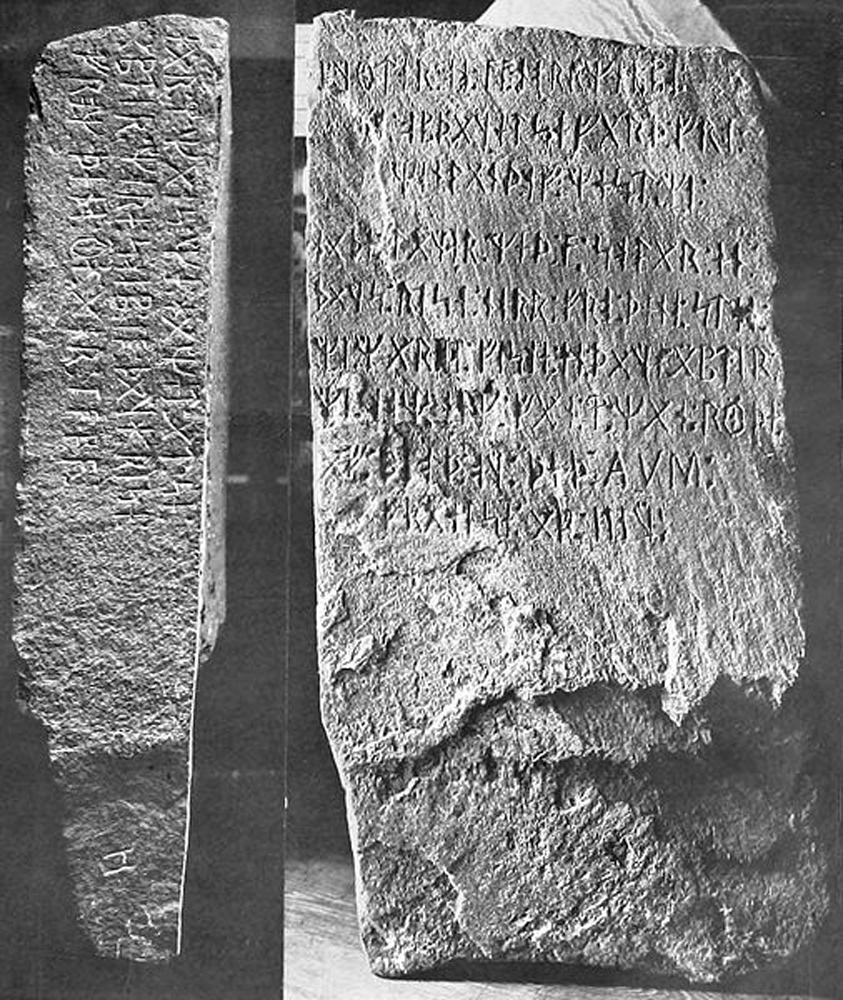

In 1898, a farmer named Olof Ohman uncovered a stone engraved with runes near the town of Kensington in Minnesota. Over the past century a number of scholars and amateurs have analyzed the stone, some believing the Kensington Runestone (shown here) was carved by a band of 14th-century Vikings on a journey into Minnesota. [Fierce Fighters: 7 Secrets of Viking Seamen]

Although the Vikings did establish colonies in Greenland and a short-lived 11th-century settlement at L'Anse Aux Meadows in Newfoundland, this stone would be the only evidence that the Vikings ever traveled to Minnesota.

Today, most scholars believe the stone was created in the 19th century, noting that the runes on the stone do not match runes from the 14th century or other medieval time periods. In fact, they seem to resemble a type of runic code used by travelers in 19th-century Sweden, wrote Henrik Williams, a professor at Uppsala University, in an article published in 2012 in the Swedish-American Historical Quarterly. Williams cautions that care should be taken in determining who wrote it and what their motivations were. The intention of the stone's inscribers may not have been to deceive people into believing that the Vikings reached Minnesota, Williams wrote. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia.)

Crystal Skulls

Crystal Skulls, supposedly from Central America, began appearing on the antiquities market in the 19th century. Claims have been made that these skulls were made by the Olmec, Maya, Toltec and Aztec civilizations. Fringe theorists have contended that the skulls were made by people from the lost city of Atlantis or extraterrestrial aliens who landed on Earth in ancient times.

Not a single one of these crystal skulls has been found in archaeological excavations, and recent research indicates they were created by forgers in the 19th and 20th centuries. Some of the forgers probably just wanted to make a buck, while others may have been interested in promoting various fringe theories, experts speculate. The 2008 movie "Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull" focused on the idea that these skulls were made by aliens.

This photo shows a crystal skull kept in the British Museum. It is not ancient but would have been made in the 19th or 20th century. It was made by humans, not an alien. (Photo by Rafał Chałgasiewicz, CC Attribution 3.0 Unported.)

Early Christian lead codices

In March 2011, a group of individuals (including some scholars) announced they had found several lead codices that could date to the first century A.D., making them the oldest Christian texts known to exist. (The full press release can be seen here.)

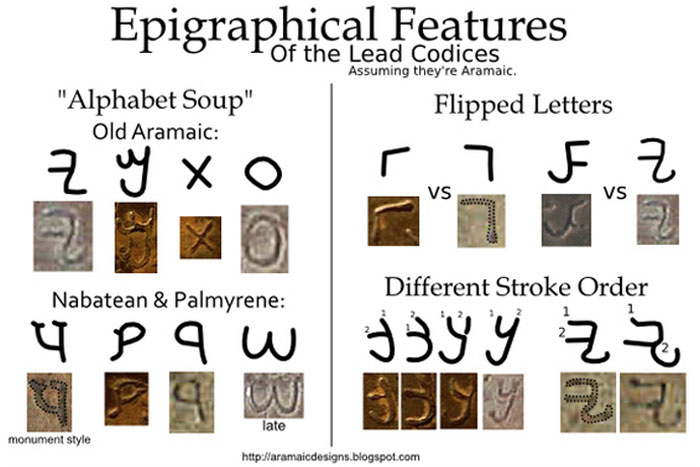

The claim garnered worldwide media headlines; however within weeks scholars had determined the codices were forgeries. "I noticed there were a lot of Old Aramaic forms that were at least 2,500 years old. But they were mixed in with other forms that were younger, so I took a closer look at that and pulled out all the distinct forms that I could find," Aramaic translator Steve Caruso told Live Science. Caruso (shown here) found that the codices contain numerous inconsistencies and anachronisms, as well as signs that it was hastily copied. Scientists don't know who created the codices, or their motives for doing so. (Image courtesy of Steve Caruso.)

Gospel of Jesus's Wife

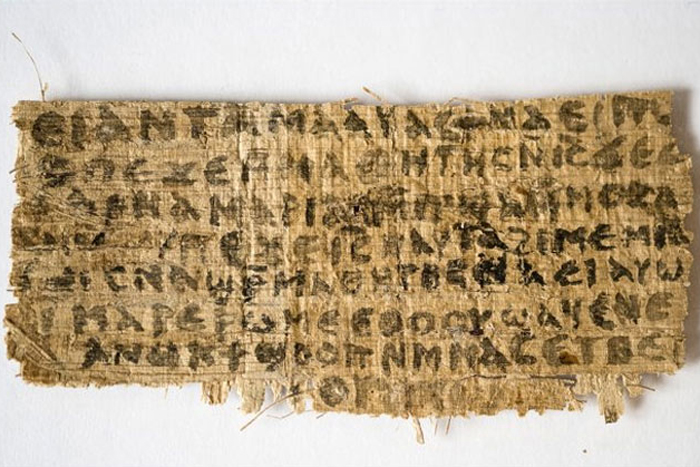

The discovery of the Gospel of Jesus's Wife was first announced by Karen King, a professor at Harvard University, in September 2012.

Written in Coptic (an Egyptian language), the fragment contains the translated line, "Jesus said to them, 'My wife …'" and also refers to a "Mary," possibly Mary Magdalene. If authentic, the papyrus suggests some people in ancient times believed that Jesus and Mary Magdalene were married.

Many scholars now believe that it is a fake.

The owner has insisted on remaining anonymous and claims to have purchased the papyrus from a man named Hans-Ulrich Laukamp in 1999 who, in turn, got it from Potsdam, in East Germany, in 1963. A Live Science investigation revealed that Laukamp was a co-owner of the now-defunct ACMB-American Corporation for Milling and Boreworks in Venice, Florida. Laukamp died in Berlin in 2002 and has no children or living relatives. The man charged with representing his estate, Rene Ernest, says that Laukamp had no interest in antiquities, never collected artifacts and did not own this papyrus. Furthermore, Laukamp was living in West Berlin in 1963 and couldn't have crossed the Berlin Wall into Potsdam.

Tests show that the papyrus itself dates back around 1,200 years and that the ink could have been made in ancient times. Scholars studying the papyrus's background and language have noted a number of unusual features, which have led most of them to conclude that it is a forgery. However King and a few other researchers still believe the papyrus could be authentic, and new scientific tests are being prepared for publication. (Photo courtesy of Harvard Divinity School.)

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.