Southern Lights Shimmer in Antarctica's Night Sky (Photo)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

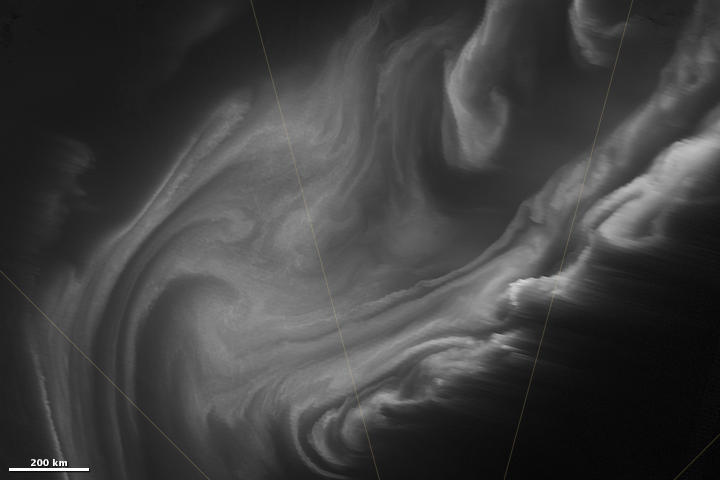

A dark, moonless sky is awash in light radiating from an aurora over Antarctica in a new image released by NASA.

The satellite photo captures the aurora australis, or "southern lights," in the early morning hours of June 24. The cloudlike swirls of light are Earth's electrical connection to the sun.

Solar flares, or intense radiation bursts from the sun, release a torrent of particles and electromagnetic energy toward Earth, flooding the atmosphere with lights that radiate around the North and South Poles. Ensuing light shows in the north are called aurora borealis, or "northern lights," and lights in the south are aurora australis. [Earth from Above: 101 Stunning Images from Orbit]

The auroras at opposite ends of the Earth are not mirror images of each other. Intense sun spots are often seen at dawn in the Northern Hemisphere in summer and at dusk in the Southern Hemisphere in winter, according to research reported in the journal Nature.

We can thank a sunspot for the brilliant aurora australis in the NASA image. Sunspot AR 12371 sizzled with flares, radio bursts and solar storms as it glided across the Earth-facing side of the sun. Between June 20 and 21, the sunspot launched a coronal mass ejection, a giant eruption of solar wind made up of energetic particles and energy from the sun, which resulted in a severe geomagnetic storm from June 22 to 23. Another flare erupted June 23 and most likely caused the light display in the NASA image.

NASA obtained the image using a "Day/Night Band" (DNB) low-light visible sensor on the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership satellite, which captures light that is difficult to discern with the human eye. The DNB can capture cloud and atmosphere features with reflected airflow, starlight and zodiacal light illumination.

Auroras are typically a relatively strong source of light, but are ephemeral and only rarely spotted at lower latitudes. The northern and southern lights can conjure thoughts of dreamlike pillars of dancing light that fill the night sky. The spectacle is called aurora for the Roman goddess of dawn, but unlike its namesake, does not follow a predictable schedule.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Astronaut Scott Kelly, who is currently on a one-year mission aboard the International Space Station, posted an aurora photograph on Twitter on June 23 that shows an upside-down Earth with a halo of luminous soft, blue light that transitions to an outer glow of cherry red.

Auroras illuminate dark skies with color when solar particles and pressure waves collide into the magnetosphere, activating particles suspended in the space around Earth, like in the radiation belt. The activated particles enter Earth's upper atmosphere, between 62 and 249 miles (100 to 400 kilometers) above the surface, excite oxygen and nitrogen molecules, and release photons of light.

Oxygen emits a greenish-yellow light or red light, and nitrogen usually radiates a blue light. The oxygen and nitrogen molecules can also emit ultraviolet light that is invisible to the human eye but can be captured by special satellite cameras. The shape the colors form can vary, from sheets to pillars to butterflylike structures, and depend on where in the magnetosphere the electrons originated and what propelled them into the atmosphere, according to NASA. Aurora shapes can morph dramatically in a single night.

Ideal places to see auroras are in Alaska, Canada and Scandinavia during the late evening hours.

Elizabeth Goldbaum is on Twitter. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus