Out-of-Body Experience Is Traced in the Brain

What happens in the brain when a person has an out-of-body experience? A team of scientists may now have an answer.

In a new study, researchers using a brain scanner and some fancy camera work gave study participants the illusion that their bodies were located in a part of a room other than where they really were. Then, the researchers examined the participants' brain activity, to find out which brain regions were involved in the participants' perceptions about where their body was.

The findings showed that the conscious experience of where one's body is located arises from activity in brain areas involved in feelings of body ownership, as well as regions that contain cells known to be involved in spatial orientation, the researchers said. Earlier work done in animals had showed these cells, dubbed "GPS cells," have a key role in navigation and memory.

The feeling of owning a body "is a very basic experience that most of us take for granted in everyday life," said Dr. Arvid Guterstam, a neuroscientist at the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden, and co-author of the study published today (April 30) in the journal Current Biology. But Guterstam and his colleagues wanted to understand the brain mechanisms that underlie this everyday experience. [Eye Tricks: Gallery of Visual Illusions]

Rubber hands and virtual bodies

In previous experiments, the researchers had explored the feeling of being out of one's body. For example, the researchers developed the so-called "rubber hand illusion," in which a person wearing video goggles sees a rubber hand being stroked, while a researcher strokes the participant's own hand (which is out of sight), producing the feeling that the rubber hand is the participant's own. The researchers have used a similar technique to give people the feeling of having a manikin's body, or even an invisible body, as they described in a report published last week in the journal Scientific Reports.

In the new study, Guterstam and his colleagues wanted to understand the brain mechanisms behind the perception of where one's body is located. Experiments in mice and other animals have shown that neurons called GPS cells are involved in navigating one's body in space (as well as in memory), a finding that was awarded the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 2014.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These studies have typically involved animals running in a virtual maze, while electrodes are hooked up to their brains. "But we don’t know what the animals perceive," Guterstam told Live Science. To better understand how the process works in people, the researchers scanned the brains of people who were experiencing the illusion of being outside their body, Guterstam said.

Out-of-body experience

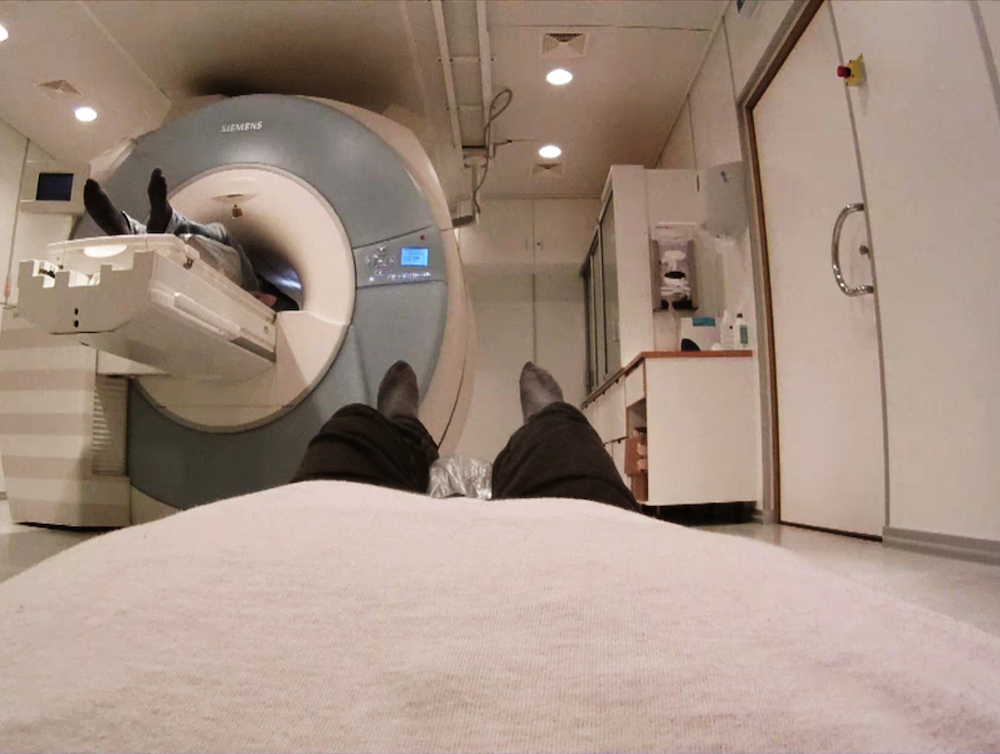

In the latest experiment, the participants lay in an MRI scanner while wearing a head-mounted display that showed video from a set of cameras elsewhere in the room. The cameras were positioned to look down on the body of a stranger, while an image of the participant's own body lying inside the scanner was visible in the background.

To produce the out-of-body illusion, the researchers touched the participants' body with a rod while simultaneously touching the stranger's body in the same place, in view of the cameras. For the participants, this technique produces the illusion that their body is in a different part of the room than where it actually is.

"It's a very fascinating experience," Guterstam said. "It takes a couple of touches, and suddenly you actually feel like you're located in another part of the room. Your body feels completely normal — you don't feel as it's floating around," he added.

Then, the researchers analyzed the brain activity in the participants' temporal and parietal lobes, which are involved in spatial perception and the feeling of owning one's body. From this activity, Guterstam and his colleagues decoded the participants' perceived location.

The researchers found that the hippocampus, a region where GPS cells have been found, is involved in figuring out where one's body is. They also found that a brain region called the posterior cingulate cortex is what binds together the feeling of where the self is located with the feeling of owning a body.

The findings could one day lead to a better understanding of what happens in the brains of people with a condition called focal epilepsy, who have seizures that affect only one half of the brain, as well as people with schizophrenia. Out-of-body experiences are more commonly reported by these groups.

It may also help to better understand the effect of the anesthetic drug Ketamine (which is used illegally for recreational purposes), which can induce similar feelings of being removed from one's own body, Guterstam said.

"We don't know what's going on in the brain [in these conditions]," he said, "but this sense of self-location could possibly involve the same brain areas" as those in his study.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.