More Big Earthquakes Coming to California, Forecast Says

A new view of California's earthquake risk slightly raises the likelihood of big earthquakes in the Golden State, but lowers the chance that people in some regions will feel shaking from smaller, magnitude-6.7 quakes.

The new report does not predict when or where earthquakes will strike, nor how big the next quake will be; instead, it provides a better sense of how often earthquakes will occur and how likely faults are to break in the next three decades. This information helps set earthquake insurance rates and building codes in California.

Under the new forecast, the likelihood of a magnitude-8 earthquake in the next 30 years has increased from about 4.7 percent to 7 percent. A magnitude-8 quake would be twice as strong as the devastating 1906 San Francisco earthquake, a magnitude 7.8. [Album: The Great San Francisco Earthquake]

Meanwhile, the analysis said that Californians should expect a magnitude-6.7 quake to occur every 6.3 years somewhere in the state, which is less than the estimate of every 4.8 years from the previous forecast, released in 2007.

According to the new model, magnitude-8 earthquakes are still exceedingly rare in California. An earthquake of that size would require an extraordinarily long break along the San Andreas Fault, something that may happen only every 500 years.

"The model is probably good news for a homeowner, because they are more threatened by a small, local earthquake than a big, rare, distant earthquake," said Ned Field, lead author of the report and a U.S. Geological Survey research scientist in Golden, Colorado.

But earthquake insurance rates and building codes may change to reflect the uptick in great earthquakes, Field said. A magnitude-8 earthquake triggers long and fast shaking that is highly damaging to buildings and structures such as bridges.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One big, faulted family

The state's magnitude-6.7 earthquake cycle slowed because scientists now calculate earthquake risk in a way that reflects how earthquakes actually happen, the report authors said. The new method takes into account that earthquakes sometimes jump across fault lines, Field said. Three of California's recent big earthquakes crossed fault lines: the 1992 Landers quake, the 1999 Hector Mine quake and the 2010 El Mayor-Cucapah quake. The 2007 study had chopped faults into pieces that broke separately during earthquakes.

"We've come to realize that we're not dealing with separate, isolated faults. We're dealing with an interconnected fault system," Field told Live Science.

California straddles the boundary between two tectonic plates — the North America and Pacific plates — that have been sliding past one another for 30 million years. Over the millennia, Earth's crust has been sliced and diced into hundreds of faults, forming an interconnected system that resembles a huge, braided river. The updated model reflects this complexity, adding 150 more faults than were included in the 2007 version. Scientists knew the faults existed in 2007, but didn't have a good idea of their potential to cause damage. GPS monitoring helped reveal how strain builds up along these newly added faults, Field said. [Image Gallery: This Millennium's Destructive Earthquakes]

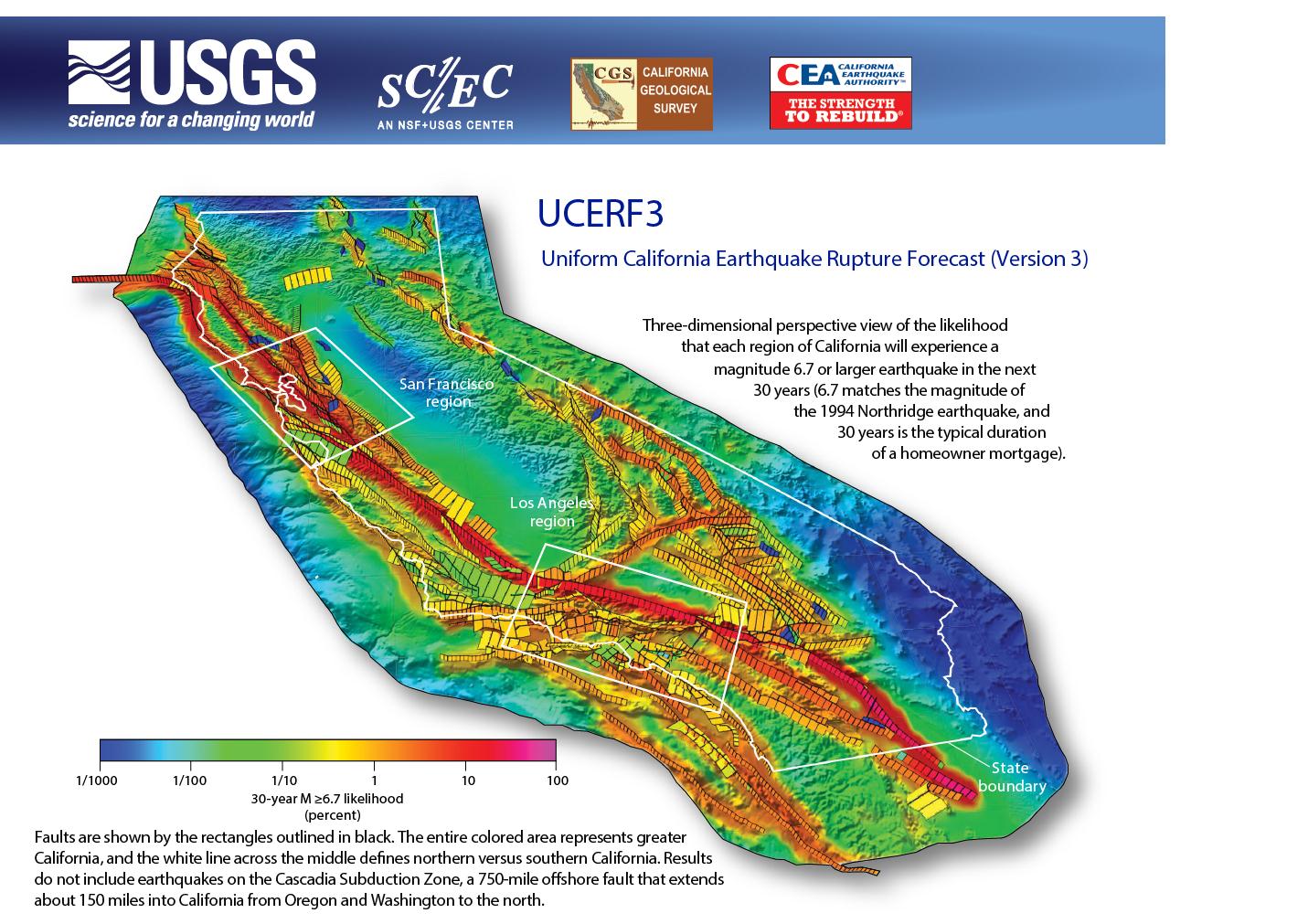

The new earthquake forecast is the culmination of a $10 million, seven-year analysis of California's faults. It brings together everything from historical earthquake reports to precise GPS monitoring of faults into a statistical model called the "Third Uniform California Earthquake Rupture Forecast" or UCERF3. It was compiled by the U.S. Geological Survey, the Southern California Earthquake Center and the state Geological Survey, with reviews by outside experts.

The report's 30-year period was chosen because it's the average length of a single-family mortgage. And a magnitude-6.7 earthquake was picked because it is the size of the 1994 Northridge quake, which wreaked havoc in Los Angeles.

The chance of another Northridge-size quake somewhere in California in the next 30 years is a near certainty, at above 99 percent, according to the report, which was released Tuesday (March 11).

San Andreas is ready to rumble

Looking at individual faults, the southern San Andreas Fault near Los Angeles poses the greatest risk over the next 30 years, the researchers said. This fault, the state's biggest, hasn't unleashed an earthquake in this region since 1857. There is a 19 percent chance that a magnitude-6.7 quake will occur on the southern San Andreas in the next 30 years, compared to 6.4 percent for the fault's northern stretch near San Francisco. Southern California's overall earthquake risk for this size temblor is 93 percent in the next three decades.

"The seismic hazards are higher in Southern California than in Northern California right now," said Tom Jordan, a report co-author and director of the Southern California Earthquake Center. "People in Southern California should realize that the next 50 years are likely to be much more seismically active. The last 50 years are not what we would consider to be normal."

In Northern California, the Bay Area's biggest earthquake risk comes from the Hayward Fault, with a 14.3 percent risk of a magnitude-6.7 quake over the next 30 years. (A short stretch of the Hayward Fault also has a higher, 22.3 percent risk over the next 30 years.)

The new forecast is a reminder that the state's nearly 40 million residents live in earthquake country, Field said. "People should live every day like it could be the day of the big one," he said.

Additional resources:

U.S. Geological Survey: A fact sheet on the new earthquake forecast.

Third Uniform California Earthquake Rupture Forecast: A Google Earth file with fault probabilities and reports describing how the model was developed.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.