Why 'Measles Parties' Are a Bad Idea

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

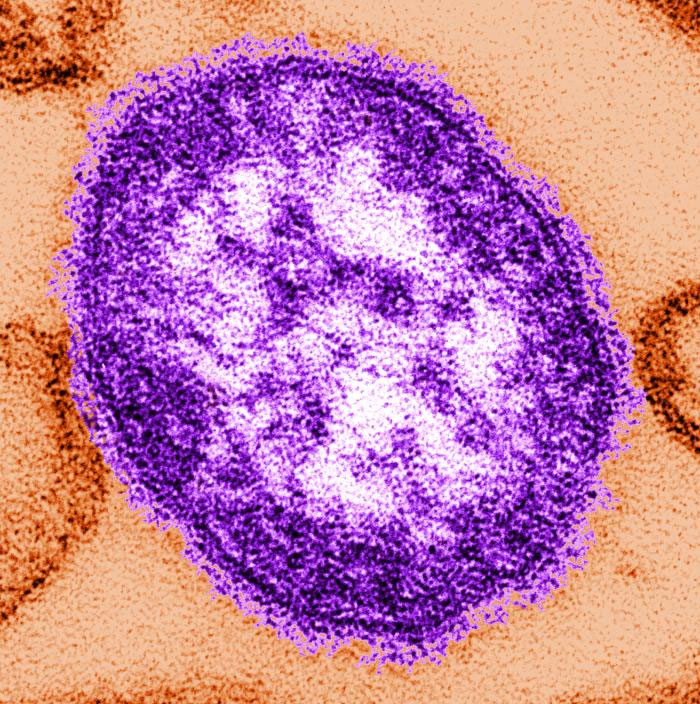

"Measles parties" that intentionally expose unvaccinated children to the illness are not a good idea, health officials said this week.

In a statement, the California Department of Public Health said it "strongly recommends against the intentional exposure of children to measles," according to the radio station KQED. Such action "unnecessarily places the exposed children at potentially grave risk and could contribute to further spread of the [measles] outbreak," officials said.

The warning came after KQED reported that a mother in Northern California had been asked if she wanted her unvaccinated children to play with a child who was sick with measles. However, the mother declined the invitation, and there have been no confirmed reports of recent measles parties in the area, according to the Los Angeles Times.

The idea for "measles parties" and "chickenpox parties" first emerged decades ago, at a time when vaccines against these diseases were not available. The thinking was that it was better to ensure that children got the disease when they were younger, and avoid getting a possibly worse form of the disease as adults, according to KQED.

But today, "it makes no sense to go through the actual illness when you can prevent it," with vaccines, said Dr. Ambreen Khalil, an infectious disease specialist at Staten Island University Hospital in New York. [Measles Outbreak: Top Questions Answered]

That's because people with measles can be very sick for seven to 10 days, with symptoms that include a high fever, cough, sore throat and rash.

What's more, a small number of children who get measles can develop severe complications from the disease, including brain infections that can cause permanent neurological damage, Khalil said. About 1 to 2 children die from the disease for every 1,000 who get it, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The complications are a lot more serious and life-threatening than anything that is seen with a vaccination," Khalil said.

Khalil said that intentionally exposing a child to an illness is never justifiable, even in places where measles or chickenpox vaccinations are not available. She noted that people who get chickenpox in childhood are at risk for the virus reactivating later in life, and developing shingles.

"These viruses are dangerous, Khalil said.

An outbreak of measles in the U.S. this year has so far sickened more than 100 people in 17 states, according to the CDC.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. FollowLive Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus