2014 Was Earth's Hottest Year On Record

Global temperatures in 2014 shattered earlier records, making 2014 the hottest year since record-keeping began in 1880, U.S. scientists reported today (Jan. 16).

Every continent set heat records last year, and the Pacific Ocean was unusually warm despite a no-show El Niño. The warmth on land and in the oceans broke previous temperature records set in 2005 and 2010, the scientists with NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) announced.

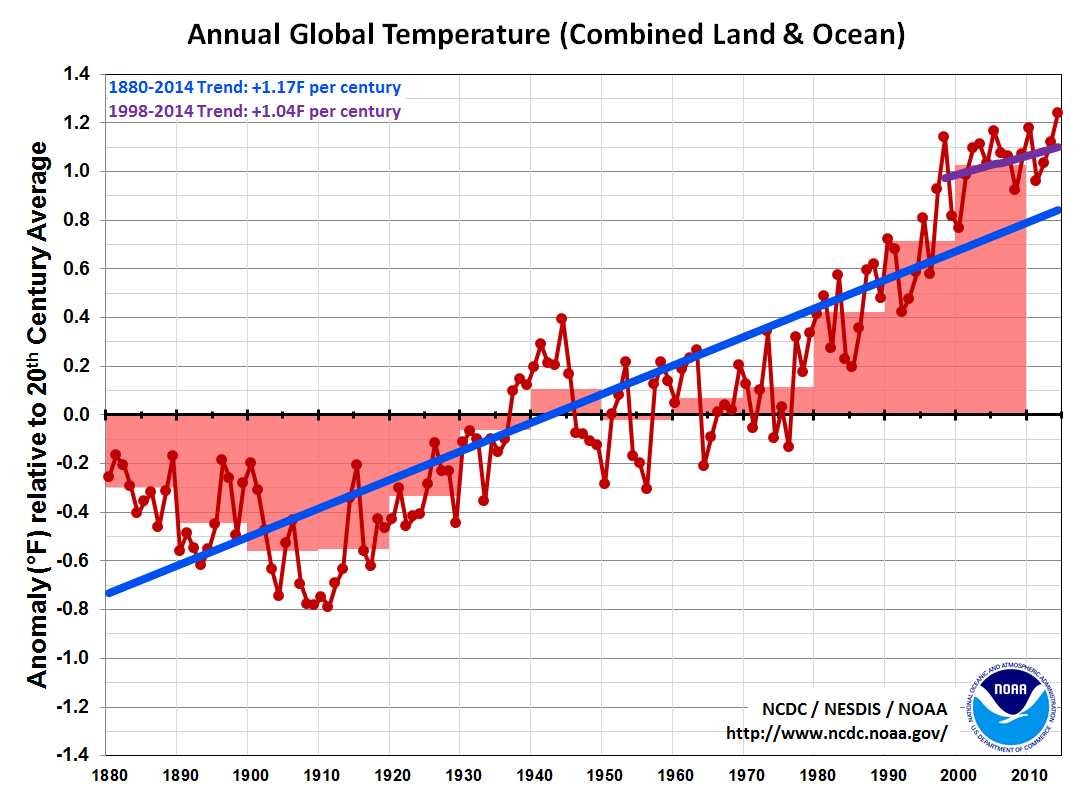

In 2014, the global average temperature was 1.24 degrees Fahrenheit (0.69 degrees Celsius) above the 20th century average of 57.1 F (14.0 C). Five months set new heat records: May, June, August, September and December. The last time the planet set a new monthly cold record was in 1916.

Nine of the 10 hottest years on record have come since 2000, continuing a relentless rise in global temperatures driven by human emissions of greenhouse gases, NASA and NOAA scientists said at the news conference today. [Hottest Year Ever: 5 Places Where 2014 Temps Really Cooked]

"It's greenhouse gases that are responsible for the majority of the long-term trend," said Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York.

Last year, carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere hit 400 parts per million for the first time, the highest in human history.

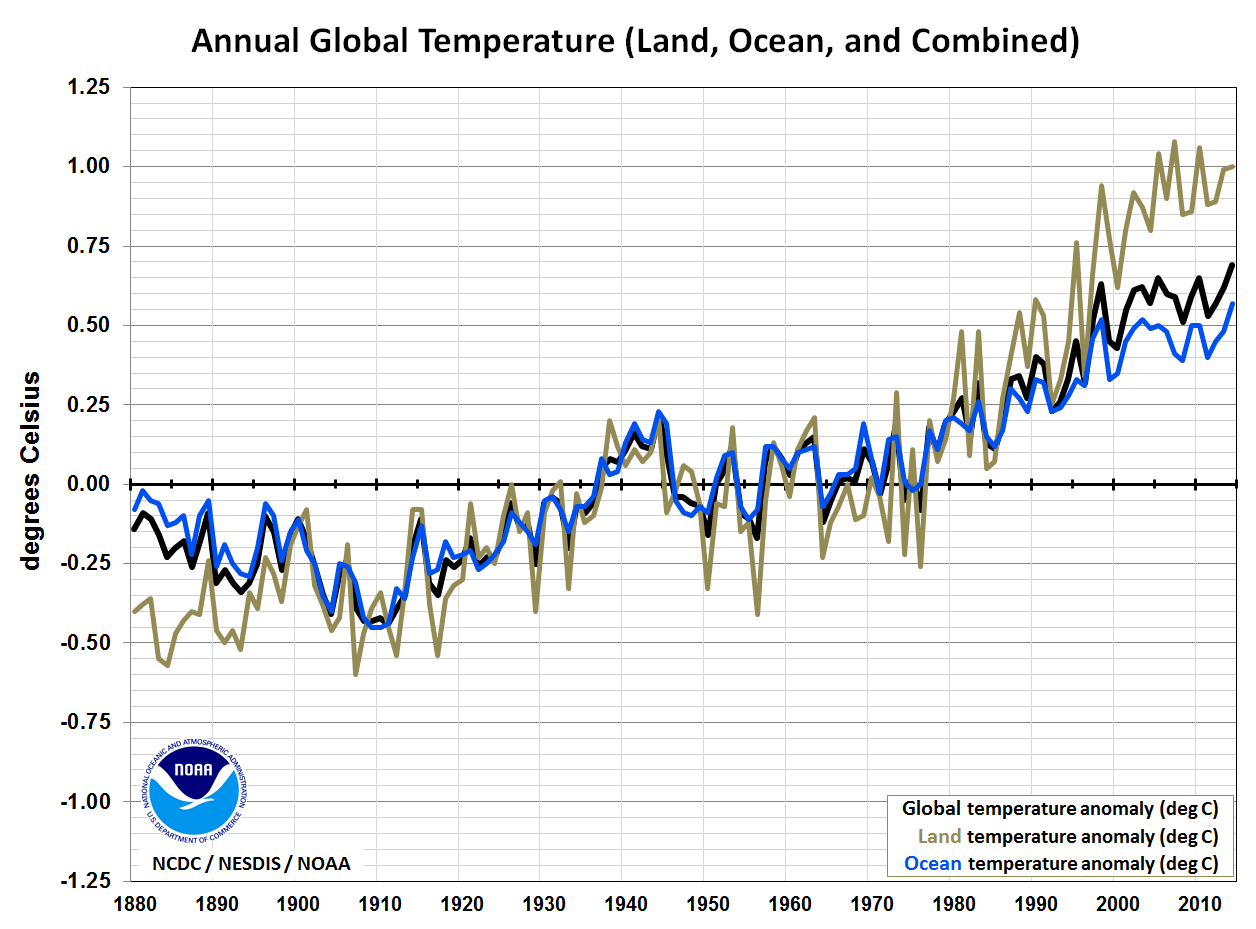

This year's temperature records are on track with warming trends since the 1970s, agency scientists said. While any year may see temperatures swing up and down from the long-term average, the overall trend reveals a steady upward rise.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We should expect these kinds of patterns to occur," said Tom Karl, director of NOAA's National Climatic Data Center in Asheville, North Carolina. "There is considerable annual variability."

Continued greenhouse gas emissions will bring more record-breaking warm years in the near future, Schmidt said. "It would not surprise me at all that the next year that started off with an El Niño would also have a record high," he said.

The Pacific Ocean's El Niño climate cycle radiates an enormous amount of heat and moisture into the atmosphere, similar to a warm humidifier chugging out steam. The 1997-1998 El Niño broke global temperature records in back-to-back years at the time; 1998 is still the fourth-warmest year on record. Yet 2014 toppled temperature records without a boost from El Niño, climate scientists noted. That's because the world is simply warmer than it was a 10 or 100 years ago. "We've got a rising baseline, so we may anticipate further record highs in the years to come," Schmidt said.

2014 has also been declared the warmest year on record by the Japan Meteorological Agency, one of the planet's four leading weather-tracking organizations. The JMA's global average temperature in 2014 was 1.1 F (0.63 C) hotter than its 20th century average, the agency announced on Jan. 6. The United Kingdom's Hadley Center also tracks global temperatures but has not released its final numbers. (NASA and NOAA are the two remaining temperature watchers).

February 1985 was the last time global temperatures fell below the 20th century monthly average, meaning no one younger than 29 has ever lived through a month cooler than the average, noted meteorologist Marshall Shepherd, director of the University of Georgia's Atmospheric Sciences Program.

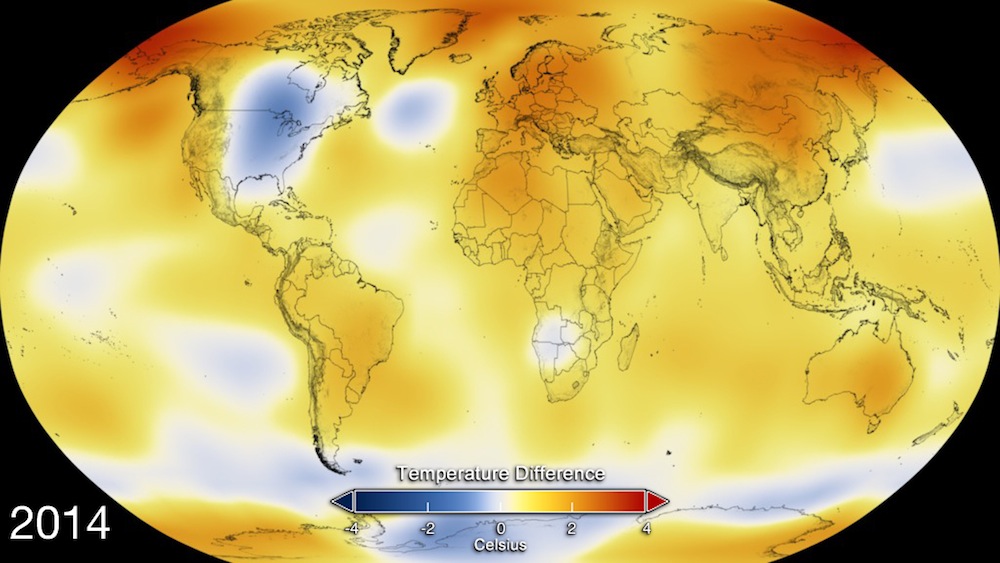

There was one notable cold spot last year: central and eastern North America, driven by the brutally cold winter of 2013-2014. Though the central and eastern United States shivered through one of its coldest winters in a generation, in the West extreme heat drove California, Arizona, Alaska and Nevada to record warm years. Portions of eastern and central Australia, eastern Siberia, Europe and central South America also roasted under record heat in 2014, NOAA reported.

Editor's note: Updated at 3 p.m. EST following a joint NASA/NOAA press conference.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.