Bone Density Drop in Modern Humans Linked to Less Physical Activity

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The relatively lightly built skeletons of modern humans developed late in evolutionary history, and may have been the result of a shift away from a nomadic lifestyle to a more settled one, according to a new study.

These findings may shed light on modern bone conditions such as osteoporosis, the scientists said.

Bone is one of the strongest materials found in nature. Ounce for ounce, bone is stronger than steel, since a bar of steel of comparable size would weigh four or five times as much. In another comparison, a cubic inch of bone can in principle bear a load of 19,000 lbs. (8,620 kilograms) or more — roughly the weight of five standard pickup trucks — making it about four times as strong as concrete. [Bone Basics: 11 Surprising Facts About the Skeletal System]

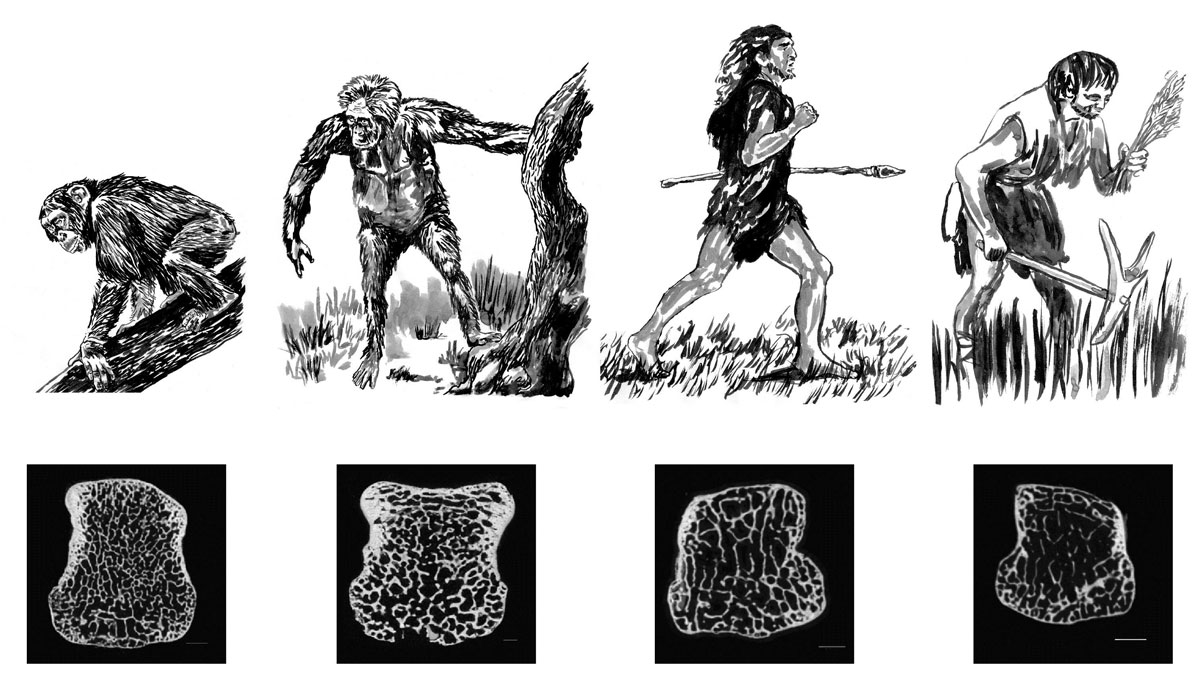

Still, modern humans have a relatively lightly built skeleton compared with those of chimpanzees — the closest living relatives of humans — as well with those of extinct human lineages.

"Throughout our skeleton, our joints are about three-quarters to one-half as dense as those of our early human ancestors and those of other modern primate species," study co-author Brian Richmond, curator of human origins at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, told Live Science. "That raises the question of when this happened in humans."

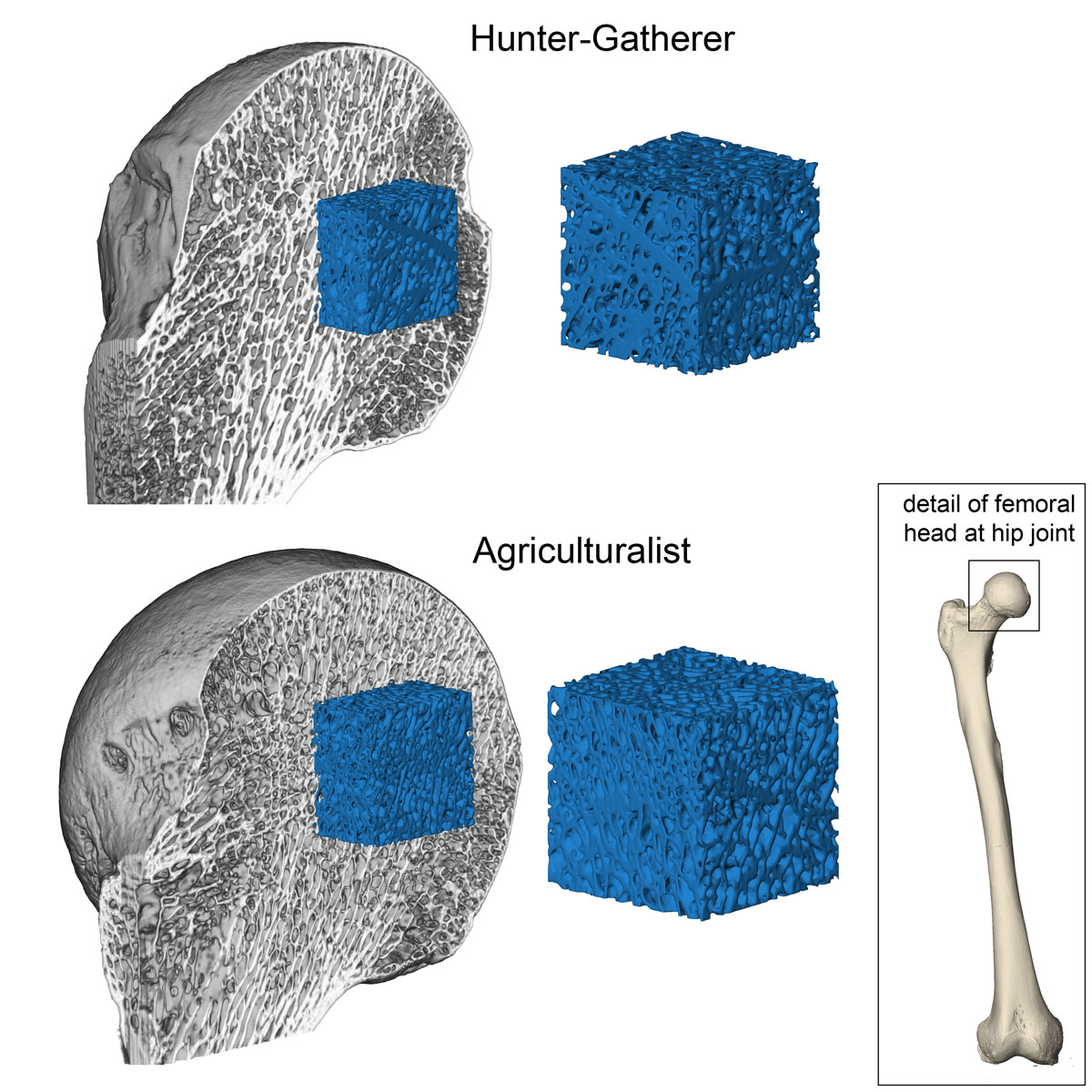

Much remains uncertain about when this unique modern human feature evolved. To shed light on this mystery, scientists examined the density of trabecular, or spongy, bone throughout the skeleton of modern humans and chimpanzees, as well as fossils of extinct human lineages spanning several million years, including Australopithecus africanus, Paranthropus robustus, Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens.

"We initially suspected that a more gracile, lightly built skeleton might be a characteristic of modern humans in general, compared to Neanderthals or our ancestors," Richmond said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Instead, the researchers discovered that the arms and legs of recent modern humans are lightly built compared not only with other living primates and with extinct human species, but also with modern humans from before the present Holocene Epoch, which began about 12,000 years ago. Rather than shifting gradually over time, bone density remained high throughout the history of human evolution, until the appearance of recent modern humans, when it decreased dramatically. [Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans]

Despite centuries of research on the human skeleton, this is the first study that shows that modern human skeletons have a substantially lower density in joints throughout the skeleton than compared to thei predecessors, Richmond said. "We've only discovered this now because our imaging technology is much higher-resolution than before, and is computationally capable of handling such images," he said.

The discovery that lightly built modern human skeletons evolved late in evolutionary history suggests that this change may have been linked to a reduction in activity due to a shift from a foraging lifestyle to a sedentary one. This idea is supported by the fact that the decrease in recent modern human bone density is more conspicuous in the lower joints of the hip, knee and ankle than in the upper joints of the shoulder, elbow and hand.

"Much to our surprise, throughout our deep past, we see that our human ancestors and relatives, who lived in natural settings, had very dense bone. And even early members of our species, going back 20,000 years or so, had bone that was about as dense as seen in other modern species," Richmond said in a statement. "But this density drastically drops off in more recent times, when we started to use agricultural tools to grow food and settle in one place."

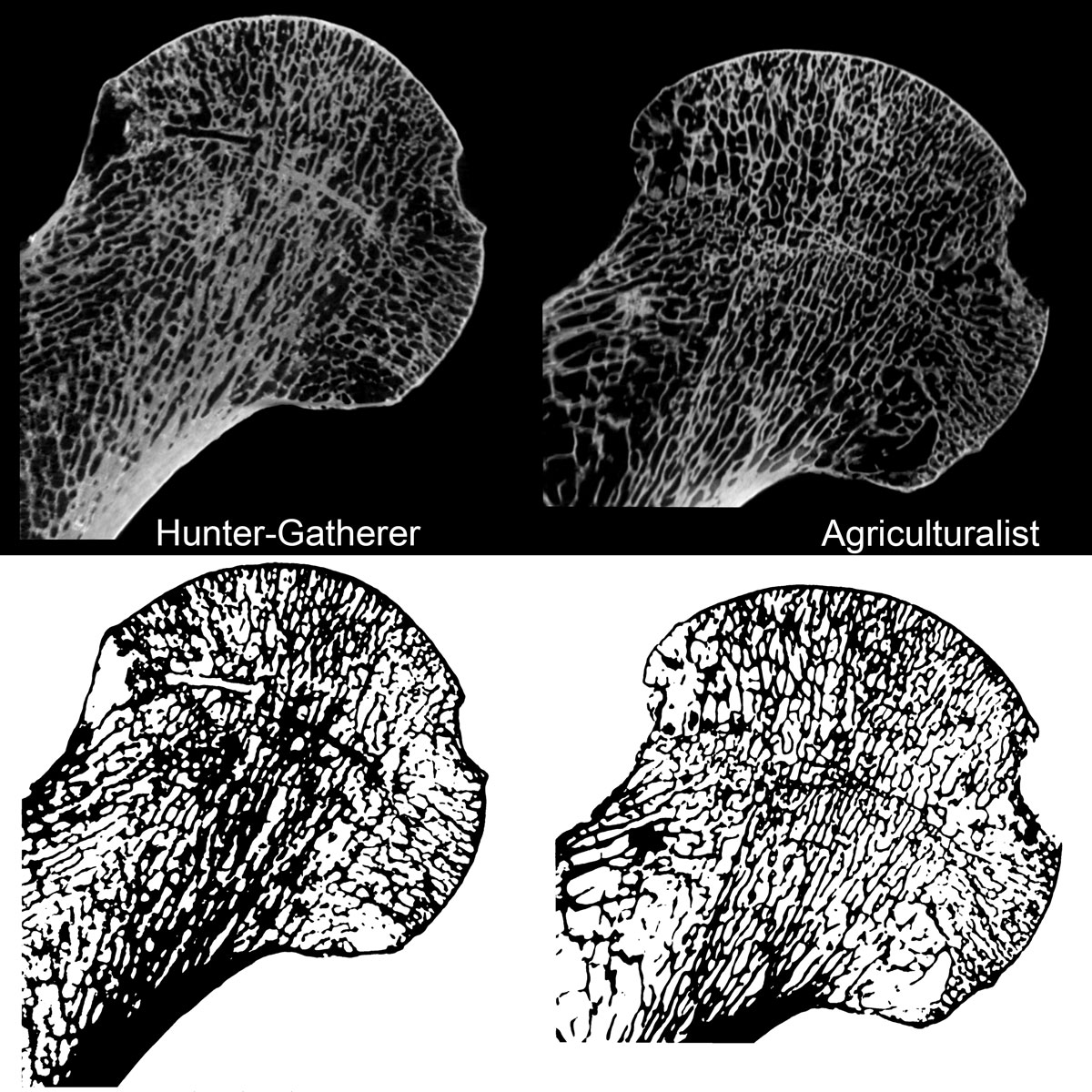

In a related study, paleoanthropologists Timothy Ryan at the University of Pennsylvania and Colin Shaw at the University of Cambridge compared the hip joints of four groups of humans — two agricultural groups and two foraging groups — that once lived in what is now Illinois. They found that the mobile-forager groups possessed significantly thicker and stronger bones in their hip joints compared with the sedentary agriculturalist groups, and the bone strength and structure of the foragers' hip joints were comparable to that of great apes. This supports the idea that changes in physical activity may explain the lightly built modern human skeleton.

"There are other things that could account for some of the differences between early agriculturalists and foragers — the amount of cultivated grains in the diet of the agriculturalists — in this case maize — as well as possible deficiencies in dietary calcium [that] may also contribute to lower bone mass," Ryan said in a statement. "However, I think the key appears to be higher physical activity and mobility from a very young age that makes the bones of nonhuman primates and human foragers stronger."

This research could yield insights into modern conditions such as osteoporosis, a bone-weakening disorder that may be more prevalent in contemporary populations, due partly to low levels of walking activity.

"This is really important for understanding our skeletal health today," Richmond said. "It's clear our skeletons evolved in a context where our species was wide-ranging and experienced lots of activity. Something we have to grapple with today is what are the consequences of our relative lack of activity. It points to the importance of exercise, especially when growing up."

The scientists detailed their findings online today (Dec. 22) in two studies in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus