Strange Rock from Russia Contains 30,000 Diamonds

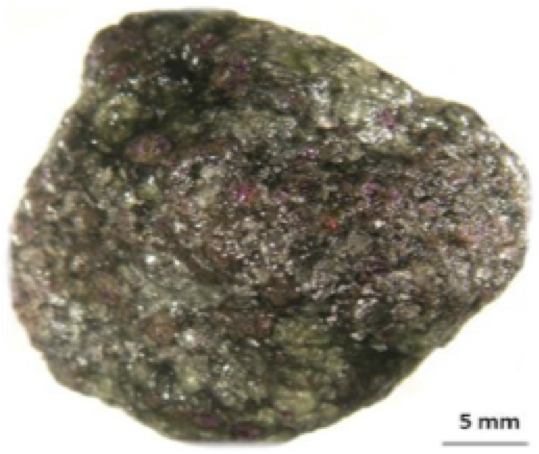

SAN FRANCISCO — Here's the perfect Christmas gift for the person who has everything: A red and green rock, ornament-sized, stuffed with 30,000 teeny-tiny diamonds.

The sparkly chunk was pulled from Russia's huge Udachnaya diamond mine and donated to science (the diamonds' tiny size means they're worthless as gems). It was a lucky break for researchers, because the diamond-rich rock is a rare find in many ways, scientists reported Monday (Dec. 15) at the American Geophysical Union's annual meeting.

"The exciting thing for me is there are 30,000 itty-bitty, perfect octahedrons, and not one big diamond," said Larry Taylor, a geologist at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, who presented the findings. "It's like they formed instantaneously."

The concentration of diamonds in the rock is millions of times greater than that in typical diamond ore, which averages 1 to 6 carats per ton, Taylor said. A carat is a unit of weight (not size), and is roughly equal to one-fifth of a gram, or 0.007 ounces. [Sinister Sparkle Gallery: 13 Mysterious & Cursed Gemstones]

The astonishing amount of diamonds, and the rock's unusual Christmas coloring, will provide important clues to Earth's geologic history as well as the origin of these prized gemstones, Taylor said. "The associations of minerals will tell us something about the genesis of this rock, which is a strange one indeed," he said.

Although diamonds have been desired for centuries, and are now understood well enough to be recreated in a lab, their natural origins are still a mystery.

"The [chemical] reactions in which diamonds occur still remain an enigma," Taylor told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists think diamonds are born deep below Earth's surface, in the layer between the crust and core called the mantle. Explosive volcanic eruptions then carry hunks of diamond-rich mantle to the surface. However, most mantle rocks disintegrate during the trip, leaving only loose crystals at the surface. The Udachnaya rock is one of the rare nuggets that survived the rocketing ride.

Taylor works with researchers at the Russian Academy of Sciences to study Udachnaya diamonds. The scientists first probed the entire rock with an industrial X-ray tomography scanner, which is similar to a medical CT scanner but capable of higher X-ray intensities. Different minerals glow in different colors in the X-ray images, with diamonds appearing black.

The thousands upon thousands of diamonds in the rock cluster together in a tight band. The clear crystals are just 0.04 inches (1 millimeter) tall and are octahedral, meaning they are shaped like two pyramids that are glued together at the base. The rest of the rock is speckled with larger crystals of red garnet, and green olivine and pyroxene. Minerals called sulfides round out the mix. A 3D model built from the X-rays revealed the diamonds formed after the garnet, olivine and pyroxene minerals.

Exotic materials captured inside diamonds, in tiny capsules called inclusions, can also provide hints as to how they were made. The researchers beamed electrons into the inclusions to identify the chemicals trapped inside. The chemicals included carbonate, a common mineral in limestone and seashells, as well as garnet.

Altogether, the findings suggest the diamonds crystallized from fluids that escaped from subducted oceanic crust, likely composed of a dense rock called peridotite, Taylor reported Monday. Subduction is when one of Earth's tectonic plates crumples under another plate. The results will be published in a special issue of Russian Geology and Geophysics next month (January 2015), Taylor said.

The unusual chemistry would represent a rare case among diamonds, said Sami Mikhail, a researcher at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C., who was not involved in the study. However, Mikhail offered another explanation for the unusual chemistry. "[The source] could be just a really, really old formation that's been down in the mantle for a long time," he said.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus