Lab-Grown Penises Could Help Men with Groin Injuries

Lab-grown penises could one day grace the groins of men who have congenital problems, complications from cancer or traumatic injuries.

Research into growing the organs in a lab is still in the experimental stages at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, the Guardian reported. The researchers said they could test the organs in people by 2019 if they gain Food and Drug Administration approval to do so.

"Our target is to get the organs into patients with injuries or congenital abnormalities," institute director Dr. Anthony Atala told the Guardian. Soldiers injured during combat could be among those who benefit, and the U.S. Armed Forces Institute of Regenerative Medicine is providing money for the study. [8 Wild Facts About the Penis]

This research project is one of many that researchers have tried over the years.

"There have been many attempts to re-create or reproduce a penis, owing to the many men who have lost their penis at some point in time," Dr. Andrew Kramer, a urologist at the University of Maryland Medical Center, told Live Science in an email.

It's difficult to make an organ that can both void urine and experience the male sexual and neurological response, Kramer said. "If [those functions are] not re-created, the engineered organ would not be successful."

"If anyone can engineer an organ, such as a penis, Dr. Atala will," said Kramer, who is not involved in the project.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Atala's research showed some success in 2008 when the institute engineered penises for rabbits. "The rabbit studies were very encouraging," Atala told the Guardian, "but to get approval for humans we need all the safety and quality assurance data, we need to show that the materials aren't toxic, and we have to spell out the manufacturing process, step by step."

To create organs for humans, the researchers plan to create penises with the patient's own cells, which could sidestep immunological rejection, Atala said.

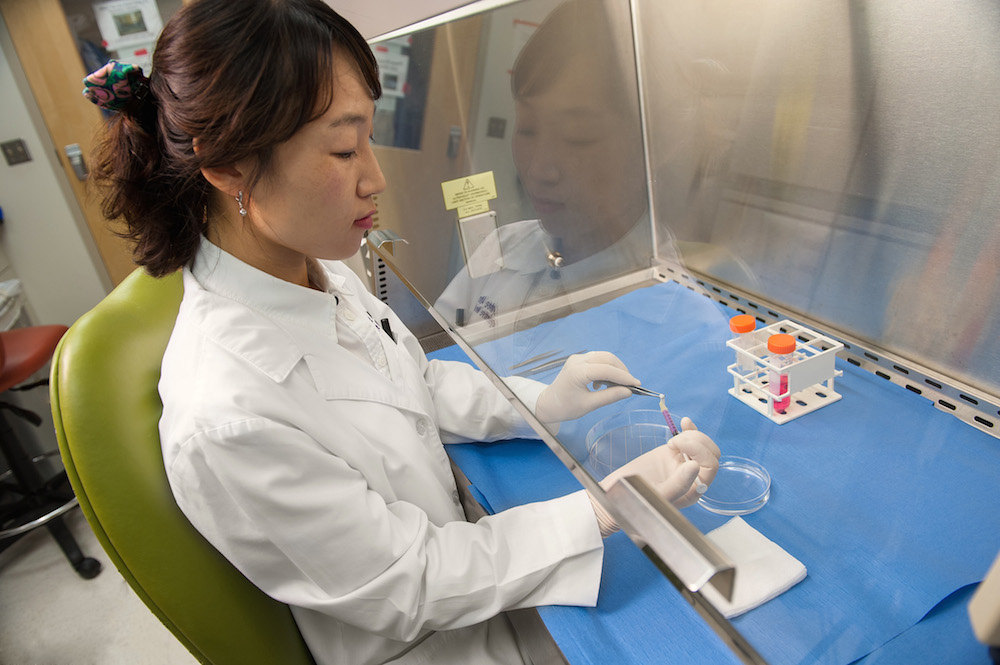

To begin, researchers would grow cells from the patients' existing genitals in the lab for four to six weeks.

Getting the right shape requires a penis donated from a deceased man. The donor organ would be washed of its own cells by soaking in a mild detergent of enzymes, to reduce the chances of rejection by the new host. That would then provide researchers with a scaffold. The researchers then plan to spread the patient's cultured cells on this scaffold, starting with smooth muscle cells and then adding the endothelial cells that line blood vessels, the Guardian reported.

"At Maryland, we are working on transplanting a penis," Kramer said. "Ultimately someone will be able to do this and offer hope to men who have lost their penis, but the technology and science today is simply not there yet, though this is promising."

Chinese doctors successfully transplanted a penis in 2006. However, the man, a 44-year-old who lost his penis in an accident, later asked for the transplanted penis to be removed, partially because his wife found it psychologically difficult.

Another option for men is for doctors to create a new penis with a flap of tissue from their forearm or thigh, Kramer said. These patients need to use a prosthetic for sexual function — either a rigid rod that creates an always-erect penis, or one that has a pump that the individual can inflate at will.

The human penis is the latest, but hardly the first organ Atala and his colleagues have tried to produce. The team created and transplanted the first human bladder in 1999, the first urethra in 2004 and the first vagina in 2005, the Guardian reported.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.