Forgotten Amber Yields New Locust Species

One of the world's largest and most pristine amber collections languished under a museum sink for decades, stashed in stainless steel buckets.

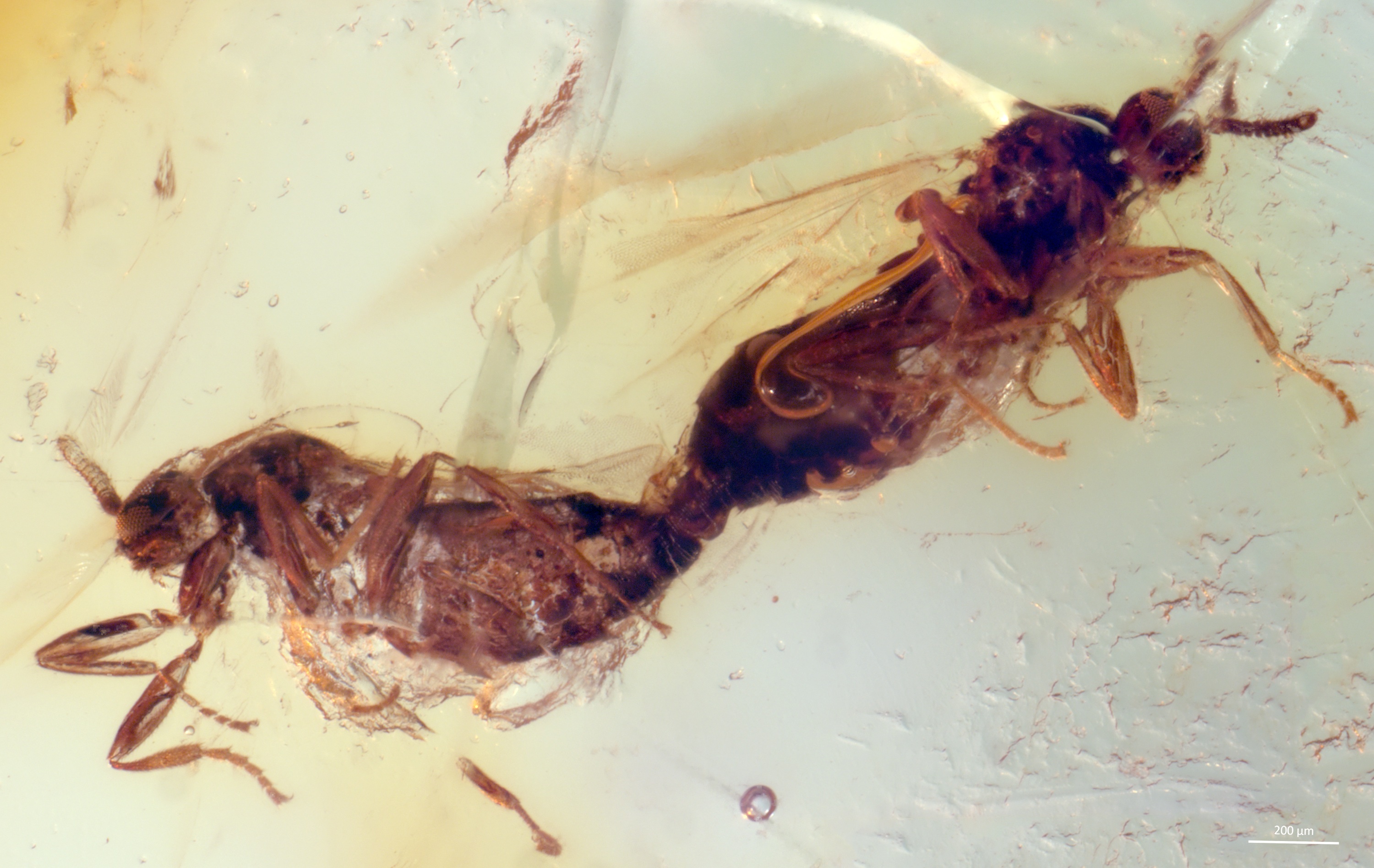

Now, scientists with the Illinois Natural History Survey are poring through the 160 pounds (73 kilograms) of raw amber from the Dominican Republic, which were collected in 1959 and rediscovered in 2011 in a closet. The researchers have already identified a new species of pygmy locust, a tiny grasshopper relative and two flies in flagrante. Other finds include ants, beetles, wasps, midges and mammal hair, all crowded together in the amber fragments, offering a rich view of the 20-million-year-old forest ecosystem. [Images: Amazing Amber Trove Rediscovered in Illinois]

"This is a massively important resource," said Sam Heads, an insect paleontologist at the Illinois Natural History Survey, who searched the museum's nooks and crannies for the amber collection. "It's probably the only unbiased amber collection in the world."

Amber collectors, even those working for museums, prize intact insects and other intriguing specimens over bits and blobs of bugs. But the collection at the Illinois Natural History Survey, a division of the Prairie Research Institute at the University of Illinois, has never been sorted for beauty or for the best specimens. "This collection has never been cherry-picked," Heads said. And that means the buckets may hold a full range of species from the ancient Miocene Epoch forest. "The insect fossil record has great potential to inform people about ancient climate and climate change," Heads said.

Entomologist Milton Sanderson unearthed the treasure trove of amber chunks in May 1959 in the Dominican Republic, armed with a government collecting permit, Heads said. Sanderson published a report of the find in the journal Science in 1960, kicking off a Dominican "amber rush," but the scientist never had time to pore through the collection, Heads said. "He was the state entomologist, and I think that was his priority," Heads said. "I think polishing the amber was a pet project he did in his spare time."

Sanderson retired from the survey in 1975 and died in 2012 at the age of 102.

Fossils in the closet

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Heads was hired as a research scientist at the survey's museum in 2011, and that's when he decided to search through its 7 million specimens for the Sanderson amber. Working with the collections manager, he struck gold in a set of 5-gallon buckets tucked in a cabinet, Heads said. "Now, we spend every day looking through this amber, and we find so many amazing things," he said.

Amber is fossilized tree resin. Before it hardened, the resin oozed and flowed over bugs and debris on branches and tree bark, trapping and preserving them for millions of years.

Dominican amber is especially valuable, because it provides a rare window into life on the forest floor. Trees there appeared either to secrete resin directly from the bases of their trunks or drop resin from their branches, entombing creatures living beneath the forest canopy, Heads said.

That's the case for the new pygmy locust species, which was fossilized in amber after its death. The wee bug is less than an inch long (20 millimeters), and foraged on lichen and algae for food. The locust's abdomen shows hints of decay, and the insect is surrounded by ants inside the amber, suggesting the ants might have been carting off the carcass for a meal.

Heads named the locust Electrotettix attenboroughi, after British naturalist and filmmaker Sir David Attenborough. A description of the new species was published today (July 30) in the journal ZooKeys.

Attenborough is Heads' childhood hero, and the famous filmmaker said he is "tickled pink" at the latest species christened in his honor. (A dinosaur, spider, armored fish and ghost shrimp are some the other creatures named for the naturalist.)

Heads and his museum colleagues said they believe the locust will be the first of many spectacular finds to come from the Sanderson amber. They have funding from the National Science Foundation to cut, polish and photograph the pieces, then post the images online in a publicly shared database.

"I think people will be researching this amber long after I'm gone," said Jared Thomas, the research assistant who creates the stunning close-ups of life forms trapped in amber. "The preservation is exquisite."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.