The Slenderman Stabbing: Are Urban Legends Really to Blame?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Last weekend, police in Wisconsin arrested two 12-year-old girls on charges of stabbing and attempted murder of a young girl, in what the girls claimed was an offering to an urban-legend character named Slenderman. Was this really a bizarre urban legend-fueled act?

The two girls are accused of luring their friend into a wooded area where one or both of the girls allegedly stabbed the victim 19 times. The motive for the alleged horrific act is even more bizarre: According to news reports, one of the girls said that many people don't believe the entity dubbed Slenderman is real and that she wanted to prove them wrong. Following one of several popular online narratives about Slenderman, the two Wisconsin girls believed they could join the villain by proving their devotion to him in killing the girl.

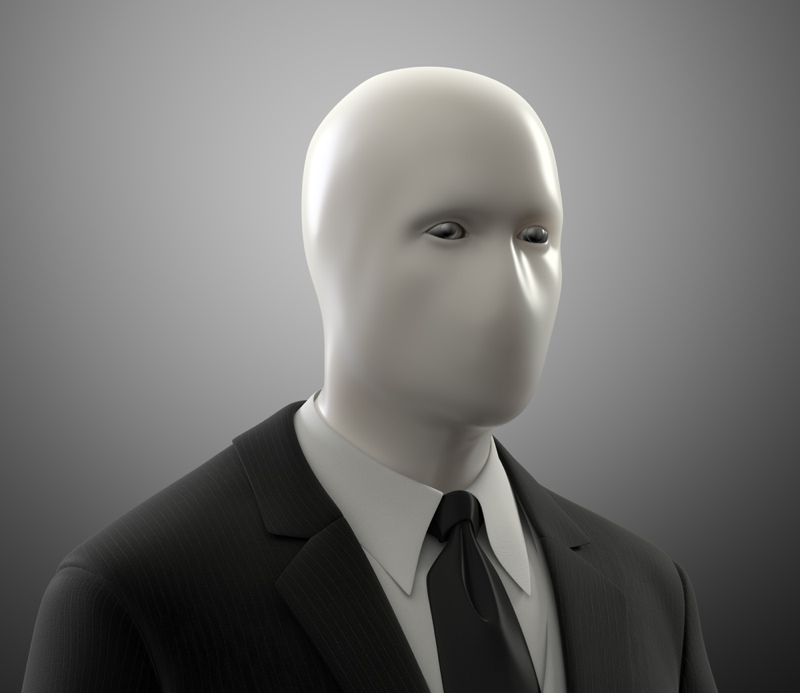

The fictional villain Slenderman was created in 2009 in an online forum and is depicted as a tall, thin, faceless evil entity dressed in a black-and-white suit. He is mute and sometimes shown as having tentacles for arms. He apparently exists solely to frighten people, especially children. Though this shady boogeyman was not created with the intent of having devotees kill in his name, he has gone through several online transformations over his virtual existence, CNN reports. [The 10 Scariest Monsters Revealed]

When most people think of legends, and particularly urban legends, they may think of scary tales told around a campfire about hook-handed escaped killers lurking in the woods. People have told that sort of tale for millennia, but the emergence of the Internet provided a whole new forum for the spread of similar legends. No longer locked in time and fixed in printed fiction, stories and legends spread around the world with a few keystrokes. Legendary figures such as Slenderman are essentially crowdsourced characters; fans write horror fiction blogs about him, create faked photos featuring him and interact with him in online alternate reality games.

For most people, of course, it's harmless fun, and they take it no further. Some people, however, engage in what folklorists call "ostension" or legend tripping, which is a form of legend transmission in which two or more people actually cast themselves in the story or legend, and play a role in it to some degree. Folklorist Jan Harold Brunvand, in his "Encyclopedia of Urban Legends" (ABC-CLIO, 2012), notes, "The concept of ostension applied to the study of urban legends recognizes that sometimes people actually enact the content of legends instead of merely narrating them as stories."

Proof of faith in legend tripping

Ostension is often harmless and occurs, for example, when ghost hunters seek out spirits in a reputedly haunted location, or when teen girls perform the Bloody Mary ritual, calling out the name in a test of nerves. In many urban legends there's an element of what's sometimes referred to as proof: demonstrating you have the nerve to do something daring.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the case of Bloody Mary legends, for example, it's usually girls proving to themselves and their friends that they have the courage to call Bloody Mary's name three (or seven, or 13) times while standing in front of a mirror in a bathroom. If you do it right, or if you have enough faith, she is said to materialize in the mirror. [Spooky Tales: The 10 Most Famous Ghosts]

According to police and news reports, the Wisconsin girls committed the stabbing for a very similar reason: In this case, the girls were allegedly trying to prove (to Slenderman and to each other) that they had the courage to stab the victim and kill her. Once the act was done, the girls believed, Slenderman would appear in front of them and lead them to his mansion, rumored to be hidden in the nearby woods. It's a classic example of ostension, albeit with much more severe consequences than most instances.

Pointing the finger

There's nothing unusual or inherently pathological about most forms of acting out fictional stories and legends; it's similar to the cosplay ("costumed play") found among fans of science fiction and fantasy, in which people dress up and act out scenes from films and TV series such as "Star Wars," "Star Trek," "Harry Potter," "Firefly" and so on. Of course, with tens (in some cases hundreds) of thousands of fans, a small percentage of them may, because of mental illness, the influence of drugs or for some other reason, take this fantasy world too far and have difficulty separating fact from fiction.

In the wake of the stabbing, some have called for one of the websites the girls allegedly used for inspiration, Creepypasta, to be taken down. But blaming Slenderman for the violent act makes no more sense than blaming Lex Luthor or any fictional villain. Still, there's a tendency to assign responsibility to media, and especially the Internet, for acts of violence such as these. In the 1980s, a concern emerged over the influence of role-playing games such as "Dungeons and Dragons" and that players who adopt the roles of wizards, assassins and thieves might somehow come to believe they actually were those characters. That concern gradually faded as games became more computer based; in the past decade, the concern has been replaced by fears over violent video games, especially the "first-person shooter" games such as "Doom" and "Call of Duty."

Whether you blame the villain or not, Slenderman has captured people's attention. Why is Slenderman so compelling? The image of a thin, menacing and silent figure in a prim suit is iconic. Variations have appeared in the popular "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" series (as the menacing "Gentlemen"), in legends and films such as "The Tall Man," and even, one could argue, in UFO folklore such as the "Men in Black."

Slenderman — like many popular horror film villains such as Leatherface in "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre," Jason Voorhees in "Friday the Thirteenth" and Michael Myers in the "Halloween" series — also has no facial features and therefore no identity. This anonymity adds to the scariness of the character, and serves another purpose, making him versatile and adaptable to many different types of media (photos, games, stories and so on).

Strange as it sounds, the two Wisconsin girls are not alone in believing that Slenderman exists — or might exist. Amid the obviously fictional horror stories of Slenderman, online forums and blogs also contain dozens of first-person accounts of people who (apparently) sincerely and genuinely believe that they have encountered the boogeyman. Hopefully, this case will serve as a caution against taking such stories too seriously.

Benjamin Radford, M.Ed., is a member of the American Folklore Society, deputy editor of "Skeptical Inquirer" science magazin, and author of seven books including "The Martians Have Landed! A History of Media Panics and Hoaxes." His Web site is www.BenjaminRadford.com.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus