Tick season: What to know about bites, removing ticks and tick-borne diseases

Knowing how to prevent and safely treat tick bites can help reduce your risk of developing tick-borne infectious diseases, such as Lyme disease and Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

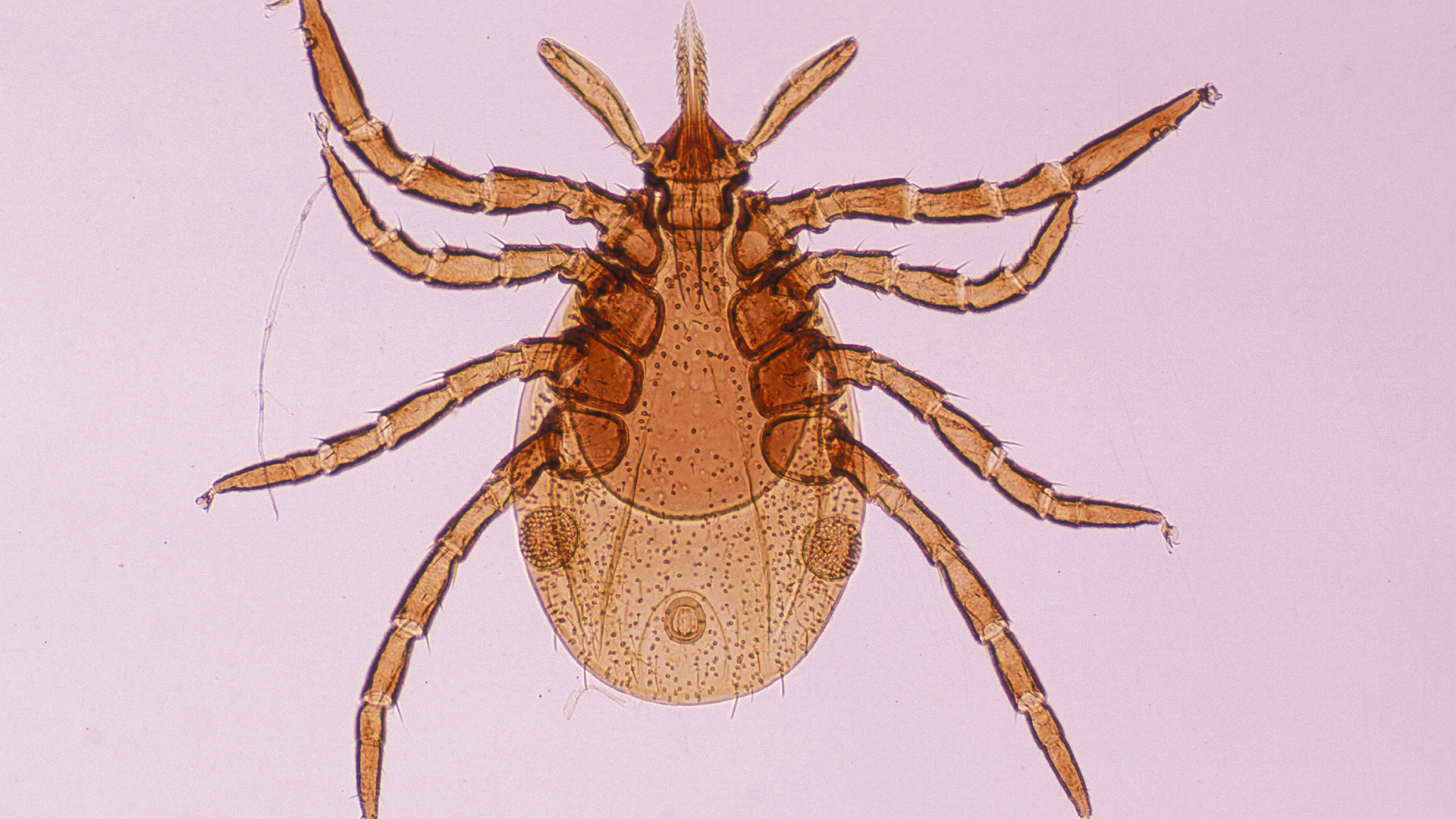

In the U.S., warm weather not only signals the coming of seasonal spring allergies but also an increased risk of tick bites. Tick bites can be harmless. But sometimes, these eight-legged creepy-crawlies can transmit diseases — such as Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) and babesiosis — to humans.

But how do you recognize a tick bite, and what is the safest way to remove a tick? Here's everything you need to know about preventing, recognizing and treating tick bites.

Related: 10 ways to avoid summer tick bites

When is tick season? And where do ticks live?

In the U.S., people can potentially be exposed to ticks any time of year, but the pests are most active between April and September. They live in grassy, brushy or wooded areas, including in people's yards.

The distribution of different tick species, which can spread different illnesses to people, varies throughout the country — for example, the blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis) is widespread in eastern states, while the Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni) lives in western states surrounding the Rocky Mountains. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) maintains a map of where different types of ticks live, although in recent years, some species have seeded new territories.

Do ticks bite humans?

Yes. Adult ticks take a "blood meal," or suck the blood, of larger hosts, including humans and deer, while immature ticks feed on smaller animals, such as mice, Dr. Gary Wormser, chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases and head of the Lyme Disease Diagnostic Center at New York Medical College in Valhalla, New York, told Live Science in an email.

Ticks go through four life stages: egg, larva, nymph and adult, according to the CDC. At every stage of this life cycle, ticks must take a blood meal.

Do ticks jump?

Ticks cannot jump or fly from a blade of grass onto a host. Rather, they hang on to the plant with their rear legs and hold their front legs aloft, waiting for something to brush by so they can grab on. This behavior is called "questing" and is critical to tick survival.

Do tick bites itch?

Tick bites don't tend to hurt or itch, and because of this, people often don't know a tick has latched onto their skin, Wormser told Live Science. That's why checking your skin for ticks is important.

Are ticks dangerous?

Most tick species are harmless to humans. Of nearly 900 tick species worldwide, only about 25 are known to spread diseases to humans. Tick species that commonly cause disease in the U.S. include the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) and the blacklegged tick.

How to prevent tick bites

You should check yourself and your pets for ticks after coming in from outdoors, so you can brush off any that have not yet latched on and use tweezers to remove any that have pierced the skin. (The CDC offers specific guidance on how to check dogs for ticks and help prevent your pet from getting ticks in the first place.)

When you hike in heavily wooded or grassy areas, stick to the center of trails and wear protective clothing, such as long sleeves and long pants, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) recommends. Applying insect repellent on exposed skin and clothing will also help prevent tick bites. Repellents registered with the EPA are best, according to the New York Department of Health.

Many ticks will not bite right after latching onto a host, instead preferring to search for a spot with thin skin. They like warmth and often head for places like the groin, armpit or hair on the head, according to the AAD. Tick checks can catch these critters before they latch on.

How to treat tick bites

It's important to remove an attached tick as soon as you can because it lowers the odds that the tick will transmit a disease. For instance, the pathogens that cause Lyme disease take several hours to transmit.

If you find a tick attached to your skin, use fine-tipped tweezers to grab the arachnid as close to the skin as possible. Pull upward evenly and steadily, without twisting, squeezing or crushing the latched tick. The goal is to remove the whole tick, without its barbed mouthparts breaking off in your skin, according to the AAD.

However, don't panic if the tick's head or mouthparts cannot be removed, Wormser said.

Related: Deadly Rocky Mountain spotted fever seen in travelers to Mexico

"They will remove themselves, like a splinter, on their own," Wormser said. Similarly, the CDC states, "If you cannot remove the mouth easily with tweezers, leave it alone and let the skin heal."

Never use chemicals or try to burn a tick to remove it, Wormser said; these remedies are more likely to make the tick cling tighter.

After you remove the tick, clean the site of the bite with soap and water or with rubbing alcohol to disinfect the wound, and then let it heal, the CDC advises. Wormser also recommends saving the tick in a jar or plastic baggie. You can then bring the tick to a health care professional, who may be able to determine the species of the tick and how long it was attached to your body.

Based on those results, if you are at risk of developing a tick-borne illness caused by bacteria, a doctor may be able to prescribe antibiotics before the onset of symptoms, Wormser said. (Note that some tick-borne illnesses are caused by other organisms, like parasites.)

You should see a doctor if you develop a rash or fever within several weeks of removing a tick, the CDC says.

What diseases do ticks carry?

According to the CDC, at least 16 illnesses can be transmitted through a tick bite in the United States. The most common, Lyme disease, affects at least tens of thousands of people in the U.S. each year and, according to some estimates, up to 476,000 people annually. Other tick-borne diseases — such as RMSF, babesiosis, tularemia and Powassan disease — are much rarer by comparison.

The risk of contracting each tick-borne disease varies by location. For example, Lyme disease is transmitted mostly by the blacklegged tick, a species widely distributed across the eastern U.S., and most cases of Lyme disease are reported in the Northeast and Upper Midwest. The Gulf coast tick (Amblyomma maculatum), on the other hand, spreads a far-less-common disease called rickettsiosis. This species lives mostly in coastal areas along the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico, according to the CDC.

That said, while most ticks live in heavily wooded areas with high levels of humidity and relatively warm temperatures, scientists suggest that climate change may lead to an increased number of ticks in places previously uninhabited by the pests, according to the EPA.

Tick-borne illnesses can be difficult to diagnose without blood tests. Many have similar symptoms, such as rash, fever, chills, aches, pains and fatigue. Various tick-borne pathogens can cause rashes, and the rashes can vary from person to person.

Ticks can also transmit more than one disease at the same time. "In the Northeast, there are at least four tick-borne infections that you can get simultaneously from the same tick," Wormser said.

Examples of tick-borne diseases

Lyme disease

Lyme disease — an infection usually caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi and, rarely, by Borrelia mayonii — can produce a wide range of symptoms that affect different parts of the body. These bacteria can be transmitted by the blacklegged tick and the western blacklegged tick (Ixodes pacificus), a species common along the Pacific coast, according to the CDC.

Common symptoms include a erythema migrans rash, also known as a "bullseye" rash, fever, fatigue and headaches. Without prompt treatment with antibiotics, the infection can spread to the heart, joints and the nervous system. The CDC has a list of questions that a doctor might ask you to see if you should get preventative antibiotics for Lyme disease after a tick bite.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

RMSF is caused by the bacterium Rickettsia rickettsii. The bacteria are spread by the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), the Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni) and the brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus), according to Johns Hopkins Medicine.

People with RMSF may have gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain. Therefore, it can sometimes be misdiagnosed as gastroenteritis, or inflammation of the digestive tract.

Antibiotics can treat RMSF. Untreated RMSF may lead to severe complications, including partial paralysis, hearing loss, nerve damage and, in rare instances, death, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Since RMSF was first recognized in 1896 in the Snake River Valley of Idaho, cases of the disease have been reported in most parts of the country, according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. It may be becoming more common: According to the CDC, the number of people diagnosed with RMSF increased from 495 in 2000 to 6,248 in 2017, although a slightly smaller number of cases were reported in 2018 and 2019.

Babesiosis

Babesiosis is caused by Babesia microti, a species of microscopic parasite that primarily infects red blood cells. Most people with this condition do not show symptoms, but some people with babesiosis can get very sick. Untreated infections can cause red blood cells to become more rigid, sticky and fragmented, which can lead to clogged arteries and respiratory problems, according to the medical resource StatPearls.

This disease can be especially dangerous for people over age of 50 and for people with compromised immune systems, Wormser said.

Babesiosis is rare in the U.S. Most reported infections occur in the Northeast and Upper Midwest, according to the CDC. However, infections with Babesia have been on the rise, increasing from 1,744 cases in 2014 to 2,418 in 2019, the CDC says.

Editor's note: This article was last updated on April 11, 2024.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Anna Gora is a health writer at Live Science, having previously worked across Coach, Fit&Well, T3, TechRadar and Tom's Guide. She is a certified personal trainer, nutritionist and health coach with nearly 10 years of professional experience. Anna holds a Bachelor's degree in Nutrition from the Warsaw University of Life Sciences, a Master’s degree in Nutrition, Physical Activity & Public Health from the University of Bristol, as well as various health coaching certificates. She is passionate about empowering people to live a healthy lifestyle and promoting the benefits of a plant-based diet.

- Nicoletta LaneseChannel Editor, Health

- Elizabeth PetersonLive Science