Data Fail! How Google Flu Trends Fell Way Short

An attempt to identify flu outbreaks by tracking people's Google searches about the illness hasn't lived up to its initial promise, a new paper argues.

Google Flu Trends, an attempt to track flu outbreaks based on search terms, dramatically overestimated the number of flu cases in the 2012-2013 season, and the latest data does not look promising, say David Lazer, a computer and political scientist at Northeastern University in Boston, and his colleagues in a policy article published Friday (March 14) in the journal Science about the pitfalls of Big Data.

"There's a huge amount of potential there, but there's also a lot of potential to make mistakes," Lazer told Live Science. [6 Superbugs to Watch Out For]

Google's mistakes

It's no surprise that Google Flu Trends doesn't always hit a home run. In February 2013, researchers reported in the journal Nature that the program was estimating about twice the number of flu cases as recorded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which tracks actual reported cases.

"When it went off the rails, it really went of the rails," Lazer said.

Google Flu Trends also struggled in 2009, missing a nonseasonal flu outbreak of H1NI entirely. The mistakes have led the Google team to re-tool their algorithm, but an early look at the latest flu season suggests these changes have not fixed the problem, according to a preliminary analysis by Lazer and colleagues posted today (March 13) to the social science pre-publication website the Social Science Research Network (SSRN).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The problem is not unique to Google flu, Lazer said. All social science Big Data, or the analysis of huge swaths of the population from mobile or social media technology, faces the same challenges the Google Flu team is trying to overcome.

Big Data drawbacks

Figuring out what went wrong with Google Flu Trends is not easy, because the company does not disclose what search terms it uses to track flu.

"They get an F on replication," Lazer said, meaning that scientists don't have enough information about the methods to test and reproduce the findings.

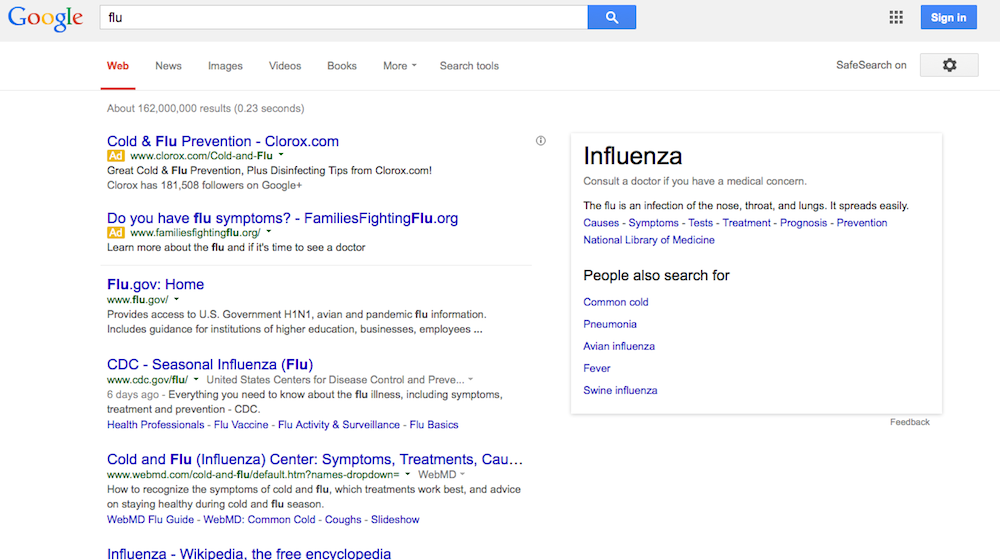

But Lazer and his colleagues have a sense of what went wrong. A major problem, he said, is that Google is a business interested in promoting searches, not a scientific team collecting data. The Google algorithm, then, prompts related searches to users: If someone searches "flu symptoms," they'll likely be prompted to try a search for "flu vaccines," for example. Thus, the number of flu-related searches can snowball even if flu cases don't. [5 Dangerous Vaccination Myths Debunked]

Another problem, Lazer said, is that the Google Flu team had to differentiate between flu-related searches and searches that are correlated with the flu season but not related. To do so, they took more than 50 million search terms and matched them up with about 1,100 data points on flu prevalence from the CDC.

Playing the correlation game with so many terms is bound to return a few weird, nonsensical results, Lazer said, "just like monkeys can type Shakespeare eventually." For example, "high school basketball" peaks as a search term during March, which tends to be the peak of the flu season. Google picked out obviously spurious correlations and removed them, but exactly what terms they removed and the logic of doing so is unclear. Some terms, like "coughs" or "fever" might look flu-related but actually signal other seasonal diseases, Lazer said.

"It was part flu detector, and part winter detector," he said.

Problems and potential

The Google team altered their algorithm after both the 2009 and 2013 misses, but made the most recent changes on the assumption that a spike in media coverage of the 2012-2013 flu season caused the problems, Lazer and his colleagues wrote in their SSRN paper. That assumption discounts the major media coverage of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic and fails to explain errors in the 2011-2012 flu season, the researchers argue.

A Google spokeswoman pointed Live Science to a blog post on the Google Flu updates that calls the efforts to improve "an iterative process."

Lazer was quick to point out that he wasn't picking on Google, calling Google Flu Trends "a great idea." The problems facing Google Flu are echoed in other social media datasets, Lazer said. For example, Twitter lets users know what's trending on the site, which boosts those terms further. [The Top 10 Golden Rules of Facebook]

It's important to be aware of the limits of huge datasets collected online, said Scott Golder, a scientist who works with such data sets at the company Context Relevant. Samples of people who use social media, for example, aren't a cross-section of the population as a whole — they might be younger, richer or more tech-savvy, for example.

"People have to be circumspect in the claims that they make," Golder, who was not involved in Lazer's Google critique, told Live Science.

Keyword choice and a social media platform's algorithms are other concerns, Golder said. A few years ago, he was working on a project studying negativity in social media. The word "ugly" kept spiking in the evenings. It turned out that people weren't having nighttime self-esteem crises. They were chatting about the ABC show "Ugly Betty."

These problems aren't a death knell for Big Data, however — Lazer himself says Big Data possibilities are "mind-boggling." Social scientists deal with problems of unstable data all the time, and Google's flu data is fixable, Lazer said.

"My sense, looking at the data and how it went off, is this is something you could rectify without Google tweaking their own business model," he said. "You just have to know [the problem] is there and think about the implications."

Lazer called for more cooperation between Big Data researchers and traditional social scientists working with small, controlled data sets. Golder agreed that the two approaches can be complementary. Big Data can hint at phenomena that need scrutiny with traditional techniques, he said.

"Sometimes small amounts of data, if it's the right data, can be even more informative," Golder said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.