George Washington Carver: Biography, Inventions & Quotes

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

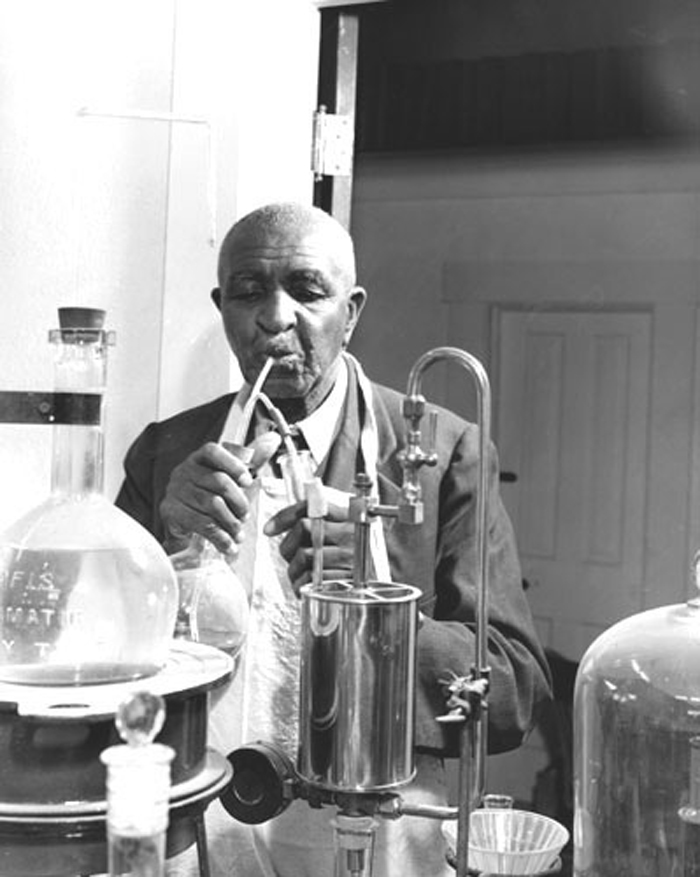

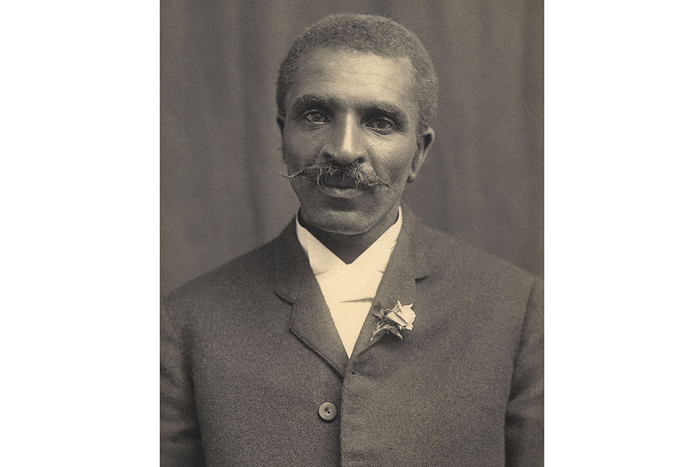

George Washington Carver was a prominent American scientist and inventor in the early 1900s. Carver developed hundreds of products using the peanut, sweet potatoes and soybeans. He also was a champion of crop rotation and agricultural education. Born into slavery, today he is an icon of American ingenuity and the transformative potential of education.

Early life

Carver was likely born in January or June of 1864. His exact birth date is unknown because he was born a slave on the farm of Moses Carver in Diamond, Missouri. Very little is known about George’s father, who may have been a field hand named Giles who was killed in a farming accident before George was born. George’s mother was named Mary; he had several sisters, and a brother named James.

When George was only a few weeks old, Confederate raiders invaded the farm, kidnapping George, his mother and sister. They were sold in Kentucky, and only George was found by an agent of Moses Carver and returned to Missouri. Carver and his wife, Susan, raised George and James and taught them to read.

Article continues belowJames soon gave up the lessons, preferring to work in the fields with his foster father. George was not a strong child and was not able to work in the fields, so Susan taught the boy to help her in the kitchen garden and to make simple herbal medicines. George became fascinated by plants and was soon experimenting with natural pesticides, fungicides and soil conditioners. Local farmers began to call George “the plant doctor,” as he was able to tell them how to improve the health of their garden plants.

At his wife’s insistence, Moses found a school that would accept George as a student. George walked the 10 miles several times a week to attend the School for African American Children in Neosho, Kan. When he was about 13 years old, he left the farm to move to Ft. Scott, Kan., but he later moved to Minneapolis, Kan., to attend high school. He earned much of his tuition by working in the kitchen of a local hotel. He concocted new recipes, which he entered in local baking contests. He graduated from Minneapolis High School in 1880 and set his sights on college.

College years

George first applied to Highland Presbyterian College in Kansas. The college was impressed by George’s application essay and granted him a full scholarship. When he arrived at the school, however, he was turned away — they hadn’t realized he was black. Over the next few years, George worked at a variety of jobs. He homesteaded a farm in Kansas, worked a ranch in New Mexico, and worked for the railroads, always saving money and looking for a college that would accept him.

In 1888, George enrolled as the first black student at Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa. He began studying art and piano, expecting to earn a teaching degree. Carver later said, “The kind of people at Simpson College made me believe I was a human being.” Recognizing the unusual attention to detail in his paintings of plants and flowers his instructor, Etta Budd, encouraged him to apply to Iowa State Agricultural School (now Iowa State University) to study Botany.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

At Iowa State, Carver was the first African American student to earn his Bachelor of Science in 1894. His professors were so impressed by his work on the fungal infections common to soybean plants that he was asked to remain as part of the faculty to work on his master’s degree (awarded in 1896). Working as director of the Iowa State Experimental Station, Carver discovered two types of fungi, which were subsequently named for him. Carver also began experiments in crop rotation, using soy plantings to replace nitrogen in depleted soil. Before long, Carver became well known as a leading agricultural scientist.

Tuskegee Institute

In April 1896, Carver received a letter from Booker T. Washington of Tuskegee Institute, one of the first African American colleges in the United States. “I cannot offer you money, position or fame,” read this letter. “The first two you have. The last from the position you now occupy you will no doubt achieve. These things I now ask you to give up. I offer you in their place: work – hard work, the task of bringing people from degradation, poverty and waste to full manhood. Your department exists only on paper and your laboratory will have to be in your head.” Washington’s offer was $125.00 per month (a substantial cut from Carver’s Iowa State salary) and the luxury of two rooms for living quarters (most Tuskegee faculty members had just one). It was an offer that George Carver accepted immediately and the place where he worked for the remainder of his life.

Carver was determined to use his knowledge to help poor farmers of the rural South. He began by introducing the idea of crop rotation. In the Tuskegee experimental fields, Carver settled on peanuts because it was a simple crop to grow and had excellent nitrogen fixating properties to improve soil depleted by growing cotton. He took his lessons to former slaves turned sharecroppers by inventing the Jessup Wagon, a horse-drawn classroom and laboratory for demonstrating soil chemistry. Farmers were ecstatic with the large cotton crops resulting from the cotton/peanut rotation, but were less enthusiastic about the huge surplus of peanuts that built up and began to rot in local storehouses.

Peanut products

Carver heard the complaints and retired to his laboratory for a solid week, during which he developed several new products that could be produced from peanuts. When he introduced these products to the public in a series of simple brochures, the market for peanuts skyrocketed. Today, Carver is credited with saving the agricultural economy of the rural South.

From his work at Tuskegee, Carver developed approximately 300 products made from peanuts; these included: flour, paste, insulation, paper, wall board, wood stains, soap, shaving cream and skin lotion. He experimented with medicines made from peanuts, which included antiseptics, laxatives and a treatment for goiter.

What about peanut butter?

Contrary to popular belief, while Carver developed a version of peanut butter, he did not invent it. The Incas developed a paste made out of ground peanuts as far back as 950 B.C. In the United States, according to the National Peanut Board, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, of cereal fame, invented a version of peanut butter in 1895.

A St. Louis physician may have developed peanut butter as a protein substitute for people who had poor teeth and couldn't chew meat. Peanut butter was introduced at the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904.

Aiding the war effort

During World War I, Carver was asked to assist Henry Ford in producing a peanut-based replacement for rubber. Also during the war, when dyes from Europe became difficult to obtain, he helped the American textile industry by developing more than 30 colors of dye from Alabama soils.

After the War, George added a "W" to his name to honor Booker T. Washington. Carver continued to experiment with peanut products and became interested in sweet potatoes, another nitrogen-fixing crop. Products he invented using sweet potatoes include: wood fillers, more than 73 dyes, rope, breakfast cereal, synthetic silk, shoe polish and molasses. He wrote several brochures on the nutritional value of sweet potatoes and the protein found in peanuts, including recipes he invented for use of his favorite plants. He even went to India to confer with Mahatma Gandhi on nutrition in developing nations.

In 1920, Carver delivered a speech to the new Peanut Growers Association of America. This organization was advocating that Congress pass a tariff law to protect the new American industry from imported crops. As a result of this speech, he testified before Congress in 1921 and the tariff was passed in 1922. In 1923, Carver was named as Speaker for the United States Commission on Interracial Cooperation, a post he held until 1933. In 1935, he was named head of the Division of Plant Mycology and Disease Survey for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. By 1938, largely due to Carver’s influence, peanuts had grown to be a $200-million-per-year crop in the United States and were the chief agricultural product grown in the state of Alabama.

Carver's legacy

Carver died on Jan. 5, 1943. At his death, he left his life savings, more than $60,000, to found the George Washington Carver Institute for Agriculture at Tuskegee. In 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated funds to erect a monument at Diamond, Missouri, in his honor.

Commemorative postage stamps were issued in 1948 and again in 1998. A George Washington Carver half-dollar coin was minted between 1951 and 1954. There are two U.S. military vessels named in his honor.

There are also numerous scholarships and schools named for him. He was awarded an honorary doctorate from Simpson College. Since his exact birth date is unknown, Congress has designated January 5 as George Washington Carver Recognition Day.

Carver only patented three of his inventions. In his words, “It is not the style of clothes one wears, neither the kind of automobile one drives, nor the amount of money one has in the bank that counts. These mean nothing. It is simply service that measures success.”

Carver quotes

"Ninety-nine percent of the failures come from people who have the habit of making excuses."

"Fear of something is at the root of hate for others, and hate within will eventually destroy the hater."

"Education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom."

"When you do the common things in life in an uncommon way, you will command the attention of the world."

"Where there is no vision, there is no hope."

"Nothing is more beautiful than the loveliness of the woods before sunrise."

"There is no short cut to achievement. Life requires thorough preparation - veneer isn't worth anything."

"Learn to do common things uncommonly well; we must always keep in mind that anything that helps fill the dinner pail is valuable."

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus