FLU FEARS: What You Can Do

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

You are probably familiar with the nasty and long-lasting symptoms of the flu: runny nose, dry cough, extreme fatigue, high fever and vomiting.

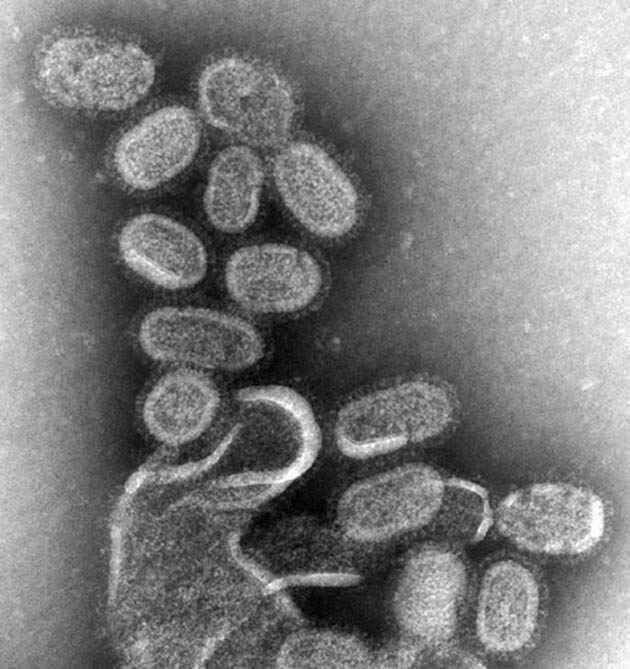

But you might know less about how to prevent infection and treat symptoms if you do become sick. This year, with the world facing the prospect of a pandemic from a bird flu that is spreading around the globe, knowing what to do is more important than ever.

In Part 2 of a three-part series, LiveScience looks at what you can do to protect yourself and those around you.

Do you need a vaccination?

Vaccines contain the virus in an amount or state that will not cause illness but that is enough for the immune system to recognize it as foreign and destroy it.

The immune system also remembers how to destroy it so that if you are ever infected by the real thing your body can quickly set to work neutralizing the virus before it infects cells or destroys infected cells.

Several major diseases – chicken pox, small pox, polio, measles, mumps, and rubella – have effective vaccines that only need to be administered once or twice a lifetime to provide protection.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But influenza is constantly changing, so yearly updates are necessary.

To insure preparedness for high-risk individuals, this year the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggested that prior to Oct. 24 vaccinations be given only to certain groups: people 65 years or older, those with chronic health, heart, or lung conditions, pregnant women, health care providers, and children six to 23 months old.

The CDC suggests that everyone else over age 50 now be vaccinated. The agency does not recommend vaccinations for other healthy individuals but says almost anyone who wants to reduce the chance of contracting the flu can be vaccinated.

However, some people should not be vaccinated, including those with severe allergies to chicken eggs, anyone who have had severe reactions to past vaccinations, and children younger than six months. People with moderate or severe illness with fever should wait until their symptoms lessen to be vaccinated.

The front lines

The first line of defense against the flu is constant surveillance of the various strains of the virus, conducted worldwide by the World Health Organization (WHO) and stateside by the CDC. This system monitors the circulating flu viruses, searching for changes that could lead to new strains.

“If a novel strain emerges, or a laboratory or doctor sees a patient and tests suggest they have a unique strain, then a sample is sent to the one of the WHO collaborating centers for flu surveillance to determine how novel it is,” explains CDC spokesperson Jennifer Morcone.

Each January the Food and Drug Administration's Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) reviews worldwide surveillance data and makes an initial recommendation about at least one of the three strains to be included in the vaccine. By mid-February, WHO officials make additional recommendations. In March the VRBPAC meets to finalize the U.S. vaccine.

(A similar process for the Southern Hemisphere wraps up in September.)

The vaccine viruses are grown inside chicken eggs in labs, so as this process is going on, the four licensed manufacturers in the U.S. begin buying enough eggs to produce 80 million or more doses of the vaccine. Once the vaccine contents have been decided on, the FDA prepares the specific viral material and sends it to each manufacturer to begin production.

Shot or spray

The flu vaccine can be administered as a shot or, for those with a fear of needles, as a nasal spray. The shot contains killed strains of the virus, which doesn't make you sick but still allows the immune system to build a resistance against the surface markers. Anyone six months or older is eligible for the flu shot.

The nasal spray, however, is approved only for use in healthy people ages five to 49. It contains live, but weakened, flu viruses that do not cause illness, sometimes called LAIV for “live attenuated influenza vaccine.”

This year's flu vaccine protects against Type A subtypes H1N1, H3N2, and Type B Shanghai, according to the CDC [more about flu types]. Since the immune system develops recognition of the H1 and N2 surface proteins, this year's vaccine also protects against H1N2, the third Type A subtype commonly circulating in the population.

The avian flu has not yet made the transformation to a version that can spread from human to human, so scientists do not know exactly what type of vaccine should be made to protect against it. If such a strain does emerge, it could take between six months and a year to produce and distribute a vaccine, said the CDC's Morcone, who added that researchers are working to replace the archaic method of egg-based vaccine development with a quicker cell culture-based technique.

Other protection

If you decide not to get a vaccination, there are a few simple things you can do to protect yourself. These preventative measure are also among the best ways to keep from catching a cold.

The virus spreads mainly through airborne liquid droplets produced by coughing and sneezing and gets into your body through any opening or mucous membrane, mainly your mouth, nose, and eyes. If you're healthy, keep your distance from people who are coughing or sneezing. If you have the flu, make sure to cover your mouth to prevent spreading it.

Experts encourage you to wash your hands. Even if you manage to stay away from airborne droplets, you might touch surfaces where those droplets have landed – from countertops to doorknobs -- and you could infect yourself by touching your mouth or rubbing your eyes.

A recent study found that 10 seconds of scrubbing with soap and water is effective at washing away most viruses. Yet in another study, only 83 percent of people leaving public restrooms had washed their hands.

If you get it

There are currently four approved antiviral treatments for influenza A viruses in the U.S., of which the best known is Tamiflu. Also known as oseltamivir, Tamiflu inhibits neuraminidase, one of the key surface proteins on the virus.

Each of these drugs needs to be taken within the first two days of the disease and will generally shorten the length of illness by one or two days.

Hoffman LaRoche, the company that produces Tamiflu, recently announced that it has produced enough of the drug to treat 55 million people this year, and the company expects to have produced enough by 2007 to treat 300 million.

However, Tamiflu may not be useful against the emerging avian H5N1 flu, should the strain transform into a human virus.

A study published in the Oct. 20 online issue of the journal Nature reported that a strain of H5N1 virus in a Vietnamese girl is resistant to Tamiflu.

There is also concern that Tamiflu can cause death or psychological problems in teenagers, following reports of Japanese teens dying or committing suicide after taking the drug. Roche argues that these effects are not the result of Tamiflu, and that high fevers and other flu symptoms could also cause psychiatric symptoms and death. The company's statement is supported by recent reports published by the European Medicines Evaluation Agency and the FDA's Pediatric Advisory Committee.

The CDC recommends that any person experiencing potentially life-threatening influenza-related illnesses, or anyone at high risk for developing complications and in the first two days of illness, be treated with antiviral medications. The agency also recommends that antiviral drugs be administered to healthy people working in an outbreak area such as a hospital to prevent the disease.

If you have the flu, health experts advise you to get plenty of rest, drink lots of liquids, avoid alcohol and tobacco products, and take fever reducers and other medication to relieve your symptoms.

Do not, however, give aspirin to a child or teenager with flu symptoms without consulting a doctor. Doing so could lead to the development of Reye Syndrome – a rare but potentially fatal disease that causes severe damage to the brain, liver and other important organs.

- SPECIAL REPORT Part 1: Flu Basics

- SPECIAL REPORT Part 2: Pandemic Primer

- U.S. Not Prepared for Flu Pandemic

- Bird Flu Pandemic Imminent, Health Official Says

- Avian Flu Could Reach U.S. Next Year

- Trojan Ducks: One More Possible Flu Carrier

- Scientists Recreate 1918 Flu Virus From Scratch

- Huge New Virus Defies Classification

- Americans' Dirty Secret Revealed

SPECIAL REPORT: FLU FEARS

What it is and how it affects us.

Part 2 : Stay Safe

How to prevent and treat the flu.

How flu could become a global killer.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus