Incredible Technology: How to Do Brain Surgery

Editor's Note: In this weekly series, LiveScience explores how technology drives scientific exploration and discovery.

Few undertakings are as complex or mired in intrigue as brain surgery.

Operating on the brain has long been the subject of horror films and sci-fi stories. In Ken Kesey's cult classic "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest," the protagonist Randle Patrick McMurphy tragically receives a lobotomy. Lobotomies — surgeries that involve severing most of the connections to and from the brain's prefrontal cortex — were widely performed from the mid-1930s through the mid-1950s. But today, surgeons have many more medically sound techniques for brain surgery.

Neurosurgery is used to prevent, diagnose, treat or rehabilitate people with disorders of the brain and its surrounding structures. Brain surgeons remove tumors, pinch off aneurysms, implant electrodes or drain blood or spinal fluid. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

People have been doing brain surgery since the Stone Age. Evidence suggests Egyptians were engaging in the practice as far back as 3000 B.C., and pre-Incan civilizations were doing it around 2000 B.C. Hippocrates (470 B.C.-360 B.C.), the father of Western medicine, wrote extensively on brain surgery and neurological conditions such as a seizures. Ancient Rome and Asia were home to many brain surgeons as well. Modern neurosurgery was pioneered by the American surgeon Harvey Williams Cushing in the early 20th century.

Many methods of brain surgery exist today. In a craniotomy, a flap of the skull is removed to provide entry to the brain. Craniotomies are commonly used to treat brain lesions or traumatic brain injury, or to implant "deep brain stimulation" electrodes to treat Parkinson's disease and epilepsy, for example. The bone flap is later replaced. In a craniectomy, the flap is not immediately replaced so that the brain can swell and reduce intracranial pressure.

Less invasive brain surgeries can be performed using an endoscope, a device that consists of a long, flexible tube with a light and camera attached that allows the surgeon to see inside the tissue while making only a small incision. Endoscopic surgeries are used to remove pituitary gland tumors, patch up spinal fluid leaks, and drain the blood that has pooled in the brain, known as a hematoma.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

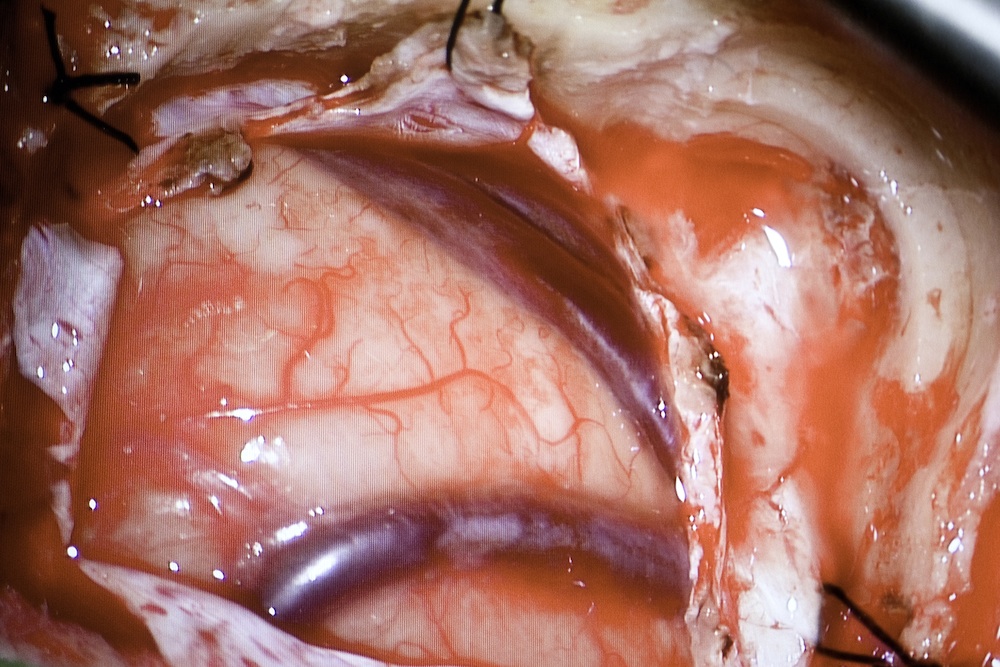

Sometimes brain surgeries are done with an operating microscope, a technique known as microsurgery. To treat an aneurysm (an abnormal bulge in a blood vessel), surgeons use a microscope to position a small metal clip on the aneurysm to block the blood flow.

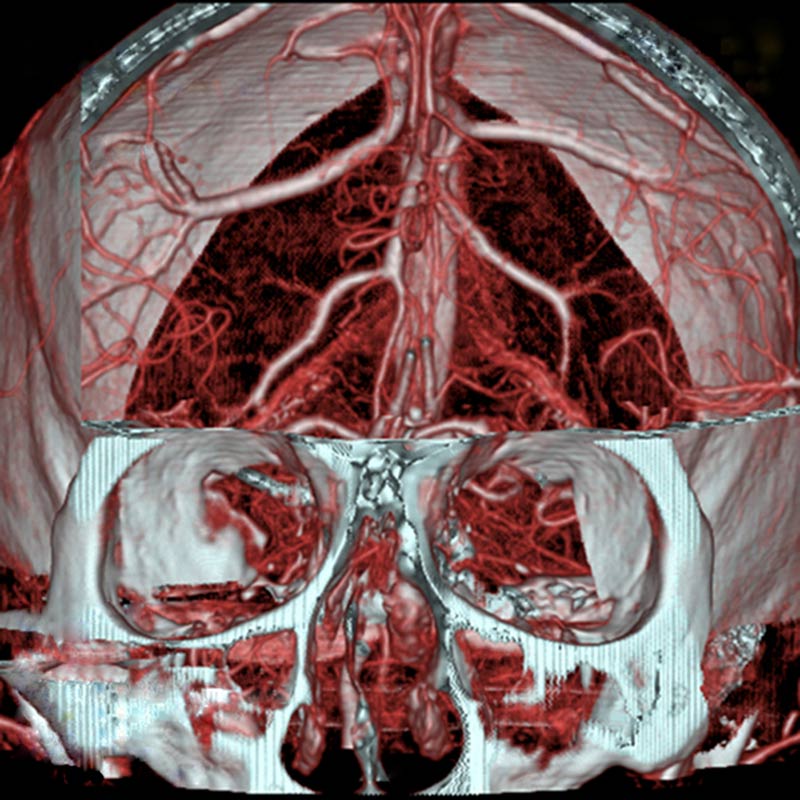

Brain imaging plays a role in many modern neurosurgical procedures. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), for example, are used to guide "stereotactic surgery" — operations that require a 3D coordinate system to target a certain spot in the brain. MRI is sometimes even used during the course of an operation.

In radiosurgery, the surgeon doesn't need to cut into the patient at all. Instead, a high-dose beam of radiation is focused at a tumor or lesion in the brain to destroy it.

Patients often undergo brain surgery under general anesthesia, but sometimes, surgery is performed while a patient is awake. For some brain tumors or forms of epilepsy, the patient must be conscious so the surgeon knows they are treating the correct brain region.

Brain surgery is by no means risk-free, but modern techniques have come a long way from the days of full frontal lobotomies. Today, a brain surgery can correct a serious disorder, or save a person's life.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus