Stunning Photo of New Solar System Captured by Amateur Astronomer

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

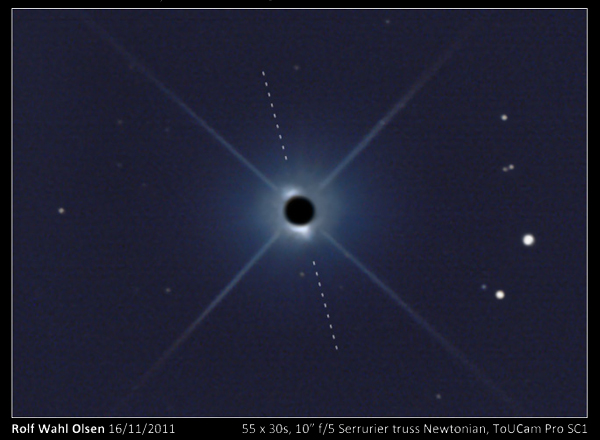

A New Zealand man has become the first amateur astronomer to take a direct photograph of a solar system in the first stages of development. Rolf Olsen's stunning image shows Beta Pictoris, a bright young star in the southern hemisphere, surrounded by a "circumstellar disk" a huge, flat cloud of swirling debris kicked up by a flurry of comet, asteroid and minor body collisions near the new star.

Olsen captured the image of the Beta Pictoris solar system, located 63 light-years away, using a 10-inch (25-centimeter) homemade telescope. After posting the photo to his blog and the Australian Amateur Astronomy forum IceInSpace, it quickly shot around the Web and into the field of view of professional astronomers, who are calling Olsen's achievement "amazing," "bold" and "impressive."

"I'm not aware of any other amateur photograph of the disk of another solar system," said Bryce Croll, an astronomer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Alain Lecavelier of the Institute of Astrophysics in Paris concurred: "This is the first image of a planetary disk made by amateur astronomer which I am aware of."

In fact, professional astronomers only managed to capture an image of a disk that of Beta Pictoris for the first time in 1984. "That an amateur can achieve this with a 10-inch telescope (even 25 years later) is nonetheless impressive," Croll told Life's Little Mysteries.

Astronomers have studied the Beta Pictoris system extensively, because it "appears to be an interesting system to inform us about the first stages of planet formation," Croll wrote in an email. The 12-million-year-old star is undergoing the same process by which our solar system formed 4.5 billion years ago. In this young and active solar system, collisions between comets, asteroids and minor planetary bodies have kicked up the disk-shape cloud of dust seen glowing in the image. [How the Solar System Formed ]

Photographing circumstellar disks is difficult, however, because light from the central star normally swamps the faint glow of the material around it. Powerful telescopes and new data filtering techniques have allowed astronomers to subtract the flood of distant starlight, revealing light from the objects near it, but most amateurs don't attempt such procedures. Olsen achieved the feat by carefully following steps outlined in an academic article about Beta Pictoris, he said.

That paper, written by Lecavelier and his colleagues, described a method of imaging the Beta Pictoris system by taking a photo of a similar reference star under the same conditions, and then subtracting an equal amount of light, pixel for pixel, from his Beta Pictoris image. "For this purpose, I used Alpha Pictoris," Olsen said. "This star is of nearly the same spectral type ... and is also close enough to Beta in the sky so that the slight change in telescope orientation should not affect the diffraction pattern." (Diffraction caused the crosshairs seen in the photo.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Olsen adjusted the exposure time of his photos of the stars to equalize their brightness. He then used simple software to subtract the image of Alpha from his image of Beta, producing a magnificent picture of the Beta Pictoris solar system with a shadowy spot in place of its central star, and the circumstellar disk radiating out from it.

"I was very excited when I saw that I had a faint signal from the disk itself. I lined up my image and checked it against the professional images, and I was happy to see that the orientation of what looked like the dust disk in my image coincided perfectly with what I could see in the professional images. It feels great to have captured this image," Olsen wrote in an email.

Croll and Lecavelier said astronomers can learn from amateur work like Olsen's.

"The techniques that Olsen applied, and similar techniques that astronomers have used for other sort of work, can be applied to a great many other stars in the sky," Croll wrote. "There certainly could be a lot of interesting things that professional astronomers have missed, that amateur astronomers could clue us in on." [Top 10 Star Mysteries]

Lecavelier added that, in particular, amateurs can help scientists by surveying the transits of exoplanets around nearby stars.

Olsen has offered a bit of advice for fellow space enthusiasts: "I'd like to encourage other amateurs to go off the beaten path every now and then and try to photograph some of the more unusual things," he wrote. "There are so many exotic targets like quasars , gravitational lenses, distant galaxy clusters, etc., which are imaged a lot less often than the more traditional nebulae and bright Messier objects. And these often have a very interesting story to tell."

- 'Infinity Symbol' Found at Center of Milky Way

- Did an Amateur Astronomer Spot a Secret Mars Base?

- A Field Guide to Alien Planets

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus