The 6 Craziest Animal Experiments

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Intro

Researchers in South Korea recently inserted a gene into the DNA of a beagle that made the dog glow green under ultraviolet light. Rather than being useful in itself, the experiment was simply an exercise in gene manipulation quite literally, a flashy stunt that could lead the way to more practical gene therapies. This is but the latest example in a long history of wacky, and sometimes ethically controversial, animal experiments, some of which have led to invaluable medical applications for humans. Here are a few of our favorite feats in the history of Frankenstein-esque science.

Multi-dog

In the 1950s, a Soviet scientist named Vladimir Demikhov pioneered the field of organ transplantation using dogs. In one infamous experiment, he fashioned a "multi-dog" surely one of the most mind-boggling creatures ever created by man.

According to a 1955 article in Time Magazine, Demikhov "removed most of the body of a small puppy and grafted the head and forelegs to the neck of an adult dog. The big dog's heart ... pumped blood enough for both heads. When the multiple dog regained consciousness after the operation, the puppy's head woke up and yawned. The big head gave it a puzzled look and tried at first to shake it off."

Remarkably, both dogs kept their own personalities, post-surgery. "Though handicapped by having almost no body of its own, [the puppy] was as playful as any other puppy. It growled and snarled with mock fierceness or licked the hand that caressed it. The host-dog was bored by all this, but soon became reconciled to the unaccountable puppy that had sprouted out of its neck. When it got thirsty, the puppy got thirsty and lapped milk eagerly. When the laboratory grew hot, both host-dog and puppy put out their tongues and panted to cool off." [Read: How Did Dogs Get to Be Dogs? ]

Unfortunately, the experiment wasn't a total success: "After six days of life together, both heads and the common body died."

Earmouse

In a slideshow of freakish animals, who could forget little earmouse. The "ear" emerging from this lab rodent's back heard nothing: It was actually just an ear-shaped tissue structure grown by seeding human cartilage cells into a biodegradable mold. The Vacanti mouse, as it's more formally known, was endowed with its ear by Dr. Charles Vacanti, a transplant surgeon, and his colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital. They performed the stunt in 1995 to demonstrate a potential method of cartilage transplantation into human patients. [Read: Why Do Medical Researchers Use Mice? ]

Huge hybrids

Not all strange animal experiments result in hideous monstrosities. Take ligers, for example the magnificent offspring of male lions and female tigers that take an inter-species shine to one another when their paths cross in captivity. At more than 900 pounds and 12 feet long, ligers are the largest cats on Earth, weighing almost 100 times more than house cats and almost twice as much as either Panthera tigris or Panthera leo. [Read: Why Don't Tigers Live In Africa? ]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Aside from spurring inexplicably gargantuan growth, "hybrid vigor" also makes these beasts healthier and sometimes longer-living than their parents. Adding to the genetic mystery of why ligers grow so large, tigons hybrids born to male tigers and female lions exhibit no such anomaly; they're just tiger-sized.

Robot monkey

{youtube wxIgdOlT2cY}

In 2010, neurobiologists at the University of Pittsburgh taught a monkey to control an advanced robotic arm with its mind. They gave the monkey two brain implants, one each in the hand and arm areas of its motor cortex. These monitored the firing of motor neurons and sent the information to a computer, which translated the patterns into commands for the robotic arm. As a result, the monkey was able to manipulate the arm, which had no less than seven degrees of freedom, with its thoughts alone. It learned to use it to reach for food pellets, press buttons and twist knobs. [Read: What's It Like to Be a Monkey? ]

The scientists weren't just monkeying around: Their work could lead to brain-machine interfaces that will allow paralyzed people to operate advanced prosthetics with their minds just as the rest of us move our fleshier limbs.

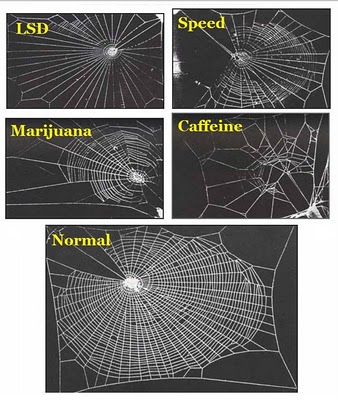

Druggy spiders

In 1995, NASA scientists studied the effects of various common drugs on the weaving abilities of spiders.They thought it might be possible to analyze the periodic structure (or lack thereof) of the drug-spun spiderwebs as a means of determining the relative toxicity levels of the drugs. Nothing much came of the effort, though perhaps owing to the difficulty of extrapolating a given chemical's toxicity to humans from its toxicity to arachnids.

That said, there did seem to be similarities between the drugs' effects on the two species. According to the researchers, the spider that was high on marijuana did a fair job weaving, but then got bored or distracted and didn't finish. The one on speed went really fast, but without much awareness of the overall picture: It left large gaps. The acid-tripping spider wove a psychedelic, symmetrical web that was very pretty but not great at catching bugs.

That brings us to caffeine. Looking at the picture, clearly the caffeinated spider did horribly, and this might point to the gulf that exists between humans and arachnids. If I were a web-weaving spider, that picture would definitely correspond to pre-coffee weaving, not post. [Read: How Do Spiders Make Silk? ]

Turkey love

When it comes to affinities for particular female body parts, turkeys are face men.

In the 1960s, turkey biologists at Pennsylvania State University found that, when placed in a room with a lifelike model of a female turkey, males mated with it as eagerly as they would a living one. Intrigued by this, the researchers then removed parts of the model, one piece at a time, to determine the minimum stimulus it would take to excite the birds before they would lose interest. Missing tails, wings, feet the amorous males couldn't care less. Even the absence of the body itself, they didn't mind: When all that remained of the model female was a head on a stick, the males still tried to mate with it.

The researchers speculated that male turkeys' head fixation relates to their mating style. When they mount a female, they cover her completely, except for her head. Because it's all they can see, the head thus becomes the focus of their erotic desires.

A strange experiment. Even stranger results. [Read: 5 Fascinating Turkey Truths ]

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus