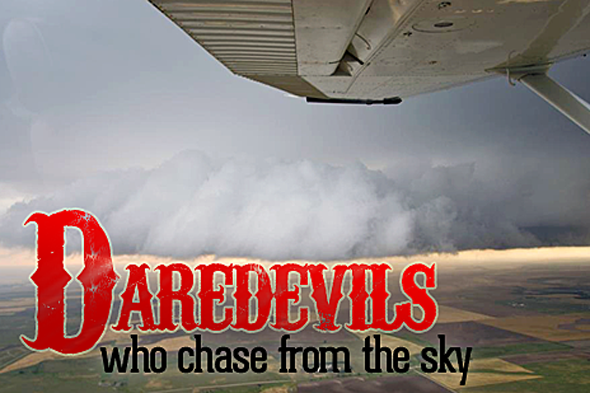

Daredevils Chase from the Sky

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This article was provided by AccuWeather.com.

Two pilots took storm chasing to a new extreme last week by chasing supercells from the sky. Caleb Elliott flew Skip Talbot and videographer Phil Bates around severe storms in North Dakota, Nebraska and Kansas.

Chasing from the air is "completely different" than chasing on the ground, Talbot said. In a car "you are limited by the road, the terrain, trees" but "you can get a lot closer... You can really feel the storm when you're on the ground. You can drive up to the tornado. You can get into the hail core. You can smell it. You can feel the wind, the rain."

In comparison, chasers in the closed environment in a plane don't feel the storm [photos].

"All the senses that you get on the ground, you don't get in the airplane..." Though the team didn't capture video of any tornadoes, Talbot said "we saw amazing supercell striation, amazing wall clouds. The views of those things were spectacular and stuff I've never really seen before from that vantage point."

To no surprise for more lily-livered ground-dwellers, Talbot, a 28-year-old computer programmer in Chicago, said that the team's first experiences with aerial storm chasing were more demanding than he thought they would be.

"When we hit turbulence, it was the kind that made you sick," Talbot said. "I got so green I was almost useless, but other than that, it was an awesome experience with fantastic views."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Elliott, a professional pilot out of Kansas City, Mo., agreed. "It's a very rare opportunity to see nature in full force, and be right up there with it, but there is a lot of tension due to the fact of how close to [the storms] you are. You are within a mile of a massive supercell thunderstorm. It can get very dangerous and deadly in a matter of seconds."

Just how dangerous is this? The obvious question for Elliott and Talbot is, "Are you crazy?" People already criticize the storm chasing community for the number of risks they take and the example they are setting for non-chasers.

"Flying near or around storms on purpose for chasing is in my opinion rather absurd," a Facebook fan of Elliott's commented on his page. "Its [sic] better to be safe on the ground than in the air in trouble wishing you were on the ground."

Talbot disagreed.

"Whenever you try something new and push the envelope, its going to be absurd and dangerous to others," Talbot replied. "Think of the risks the first pilots took, and what we wouldn't have today if it weren't for them. Plenty of good pilots died along the way, but they knew the risks going in and they followed their dreams."

"STORM CHASING IS DANGEROUS NO MATTER WHERE YOU ARE," Elliott responded to the poster.

By phone, Elliott expanded on that statement. "It's very dangerous," Elliott said. "I don't condone any of this. I know what my experience is and I'm comfortable with it. It is dangerous and nobody needs to be doing it."

Not many people are qualified to do what Elliott and Talbot do either.

"Ninety percent of pilots know nothing about severe weather," Elliott estimated. "Ninety percent of storm chasers know nothing about flying an airplane."

Both men are trained storm spotters for the National Weather Service. Both are pilots. Both have long resumes of storms chased.

Elliott is a commercial pilot and is a certified flight instructor, among a long list of other certifications. He got his pilot's license at age 12. ("Part of the reason I got my pilot's license is so I could be up closer to the weather," Elliott said. "Aerial storm chasing is the direction I've always wanted to go.") He flies cargo planes full time and understands how many ways a thunderstorm can bring a plane down.

A horrible experience piloting a plane through a line of thunderstorms back in 2008 steeled Elliott's resolve to learn how to handle the atmosphere's violence.

"It was one of the most terrifying experiences of my life," the pilot said. "I didn't think I was coming out of the other side."

Though the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) recommends pilots fly no closer than 20 miles to a severe thunderstorm, a fellow "freight dog" taught Elliott how to deal with flying near unexpected severe weather.

"A thunderstorm packs just about every weather hazard known to aviation into one vicious bundle," a document from the FAA reads. "Almost any thunderstorm can spell disaster for the wrong combination of aircraft and pilot."

Elliott and Talbot have flown as close as one mile to a supercell. The recommendation is "greater than 20 years old," Elliott countered. "We know so much more about thunderstorms [now] that it is no longer really applicable... Part of the reason I want to do aerial storm chasing is to increase aeronautical knowledge of severe thunderstorms and tornadoes."

From a meteorologist's perspective, there is some value to aerial storm chasing flights.

"Looking at their footage, I realize there's a lot about storms that we can't see from the ground," AccuWeather meteorologist Jesse Ferrell said. "I think aerial storm research will be important for the future of meteorology -- if we can do it safely."

© AccuWeather.com. All rights reserved. More from AccuWeather.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus