Slabs of North American Continent Are Layered Like Cake

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The continent of North America is not a single, thick, rigid slab, but is instead more similar to a layer cake, with a section of 3-billion-year-old rock sitting atop much newer material, a new study that probes the depth of the continent finds.

The finding helps explain how the Earth's continents formed, researchers said.

"This is exciting because it is still a mystery how continents grow," said study researcher Barbara Romanowicz, director of the UC Berkeley Seismological Laboratory.

"We think that most of the North American continent was constructed in the Archean (eon) in several episodes, perhaps as long ago as 3 billion years, though now, with the present regime of plate tectonics, not much new continent is being formed," Romanowicz said.

How cratons form

The Earth's original continents started forming some 3 billion years ago when the planet was much hotter and convection in the mantle more vigorous, Romanowicz said. The continental rocks rose to the surface and eventually formed the lithosphere, Earth's hard outer layer that includes the planet's crust and a portion of the upper mantle.

These old floating pieces of the lithosphere, called cratons, apparently stopped growing about 2 billion years ago as the Earth cooled, though within the last 500 million years, and perhaps for as long as 1 billion years, the modern era of plate tectonics has added new margins to the original cratons, slowly expanding the continents.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One of those original continents is the North American craton, located mostly in the Canadian part of North America.

The history of the Earth's oldest continental plates is vague, because details of their interiors are hidden from geologists. The deep interior of the North American craton is known only from so-called xenoliths rock inclusions in igneous rock (formed from molten magma) or xenocrysts such as diamonds that have been delivered to the surface from deep below by volcanoes.

Seismologists, however, have the ability to probe the Earth's interior thanks to seismic waves from earthquakes around the globe, which can be used much like sound waves are used to probe the interior of the human body.

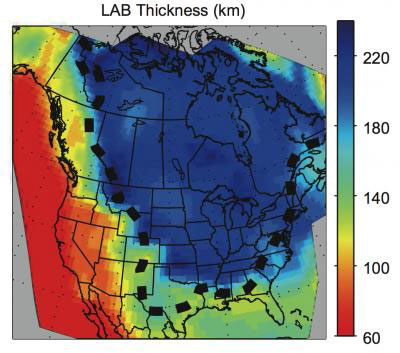

Such seismic tomography has established that the bottom of the North American craton is about 155 miles (250 kilometers) deep at its thickest, thinning out toward the margins where new chunks have been added to the continental lithosphere.

The new study suggests that any continental lithosphere that has been added since the original North American craton formed came from material scraped off of the ocean floor as the craton plunged beneath the continent and not deposited from below by plumes of hot material welling up through the mantle, as happens at volcanoes and mid-ocean ridges on the seafloor.

Layered continental cake

Romanowicz and UC Berkeley postdoctoral fellow Huaiyu Yuan found the boundary between the old craton and the younger material while using a new seismic technique to locate the boundary between the lithosphere and asthenosphere, the softer material below the lithosphere on which the continental and oceanic plates ride .

Instead, they found a sharp boundary 93 miles (150 km) below the surface, far too shallow to be the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary. The scientists think the sharp boundary is between two types of lithosphere: the old craton and the younger material that should match the chemical composition of the sea floor. Their interpretation fits with studies of xenoliths and xenocrysts, which indicate that there are two chemically distinct layers within the Archean crust.

Another study conducted three years ago that also used seismic waves to probe the Earth's deep layers found a sharp boundary at a depth of about 75 miles (120 km).

"We think they are seeing the same layering we are seeing, a sharp boundary within the lithosphere," Romanowicz said.

Romanowicz thinks their study will help scientists further tease apart the formation of the continents.

"I think our paper will stimulate people to look more carefully at distinguishing the ages of the lithosphere as a function of depth," she said. "Any information we can provide that constrains models of continental formation is really useful to the geodynamicists."

The study is detailed in the Aug. 26 issue of the journal Nature.

- 101 Amazing Earth Facts

- Canadian Rocks Stake a Claim as Earth's Oldest

- Have There Always Been Continents?

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus