North America's 'broken heart': The billion-year-old scar from when the continent nearly ripped apart

The Midcontinent Rift is a giant tear that formed in what is now the U.S. Midwest 1.1 billion years ago. Nicknamed North America's "broken heart," it is filled with solidified magma and lava.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Name: The Midcontinent Rift

Location: U.S. Midwest

Why it's incredible: The rift nearly broke North America in half around 1 billion years ago.

North America's "broken heart" is an ancient rift valley in the Midwestern United States. The rifting began roughly 1.1 billion years ago due to tectonic forces pulling what is now the North American continent in opposite directions. Evidence suggests the rifting process stalled about 100,000 years after it began, but scientists aren't sure why.

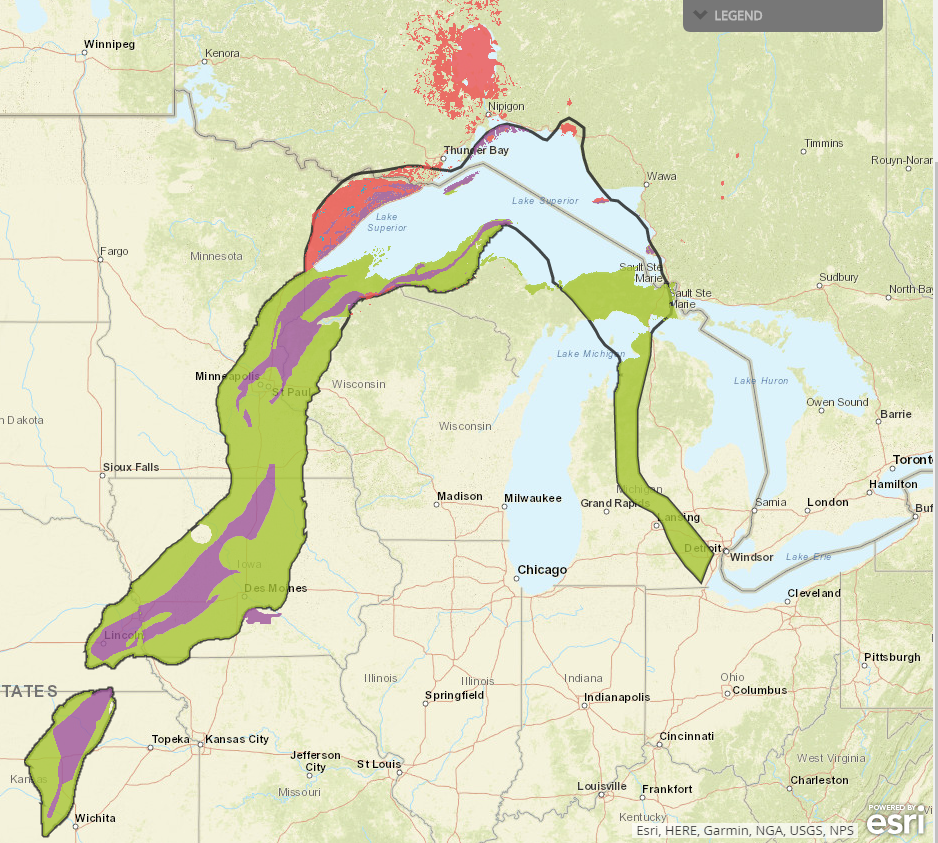

The rift valley is shaped like a horseshoe, stretching from Kansas north to Lake Superior and south again to Michigan, according to maps from a 2013 article in Nature — although some evidence suggests the rift might extend farther south. Geologists estimate that the rift once measured around 1,900 miles (3,000 kilometers) long and created a basin as wide as the Red Sea, but most of the structure is now buried beneath a thick layer of sediment, according to the National Park Service (NPS).

The only parts of the rift that are visible today are near Lake Superior, where huge blocks of basalt and other rift-related rocks are exposed, according to the NPS. Basalt is a dark, fine-grained — and, therefore, dense — rock formed from rapidly cooling lava. As Earth's crust was ripped apart during the rifting process, magma rose to fill the crack, creating a belt of solidified lava and magma in the valley.

The rift likely opened in what is now the Midwest because Earth's crust was already fragile there — a large blob of magma may have weakened the surface and sealed the region's fate, according to the NPS. As the rifting progressed, molten rock rose and triggered volcanic eruptions, depositing huge amounts of dense material, such as basalt, that caused the rift valley to sink into the crust.

A "spectacular failure"

For reasons that scientists debate, rifting and the eruptions stopped, so sediment settled on top of the volcanic material. But the rift valley didn't stop sinking, because the weight of the sediment pushed the structure deeper into the crust.

Related: Upheaval Dome: Utah's 'belly button' that has divided scientists since its discovery

Rifting was followed by a period of compression, in which chunks of crust on each side of the rift valley were squished together. This pushed up the volcanic material and sediment, according to the NPS, exposing sections of the rift valley that were then covered up by sediment.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The cyclical growth and melting of glaciers over the past 2.5 million years removed some of that sediment, which is why parts of the rift are still visible. Near Lake Superior — particularly on northern Michigan's Keweenaw Peninsula — basalt and copper-rich rocks emerged. People have mined this copper for at least 8,000 years — and although the mines closed in the late 20th century, the industry is now seeing a revival.

Why the rifting ended after 100,000 years remains somewhat unclear.

"It's a spectacular failure," G. Randy Keller, a professor emeritus of geophysics at the University of Oklahoma and the director of the Oklahoma Geological Survey, said in the 2013 Nature article. "How that feature could just totally reorganize the crust of the Earth in the Lake Superior region and not manage to break the continent apart is fairly amazing."

Geologists have been exploring this question for more than a decade, with some scientists linking the failure to a mountain-building episode along North America's Atlantic coast. Other researchers reject this theory, proposing instead that the rifting ended when a sea opened between Laurentia and Amazonia — the geologic cores of North and South America.

Meanwhile, sections of the rift valley in Kansas have attracted attention from resource exploration companies. Basalt can react with water to make hydrogen, which is a source of clean energy and an ingredient in key chemicals, Live Science previously reported.

Discover more incredible places, where we highlight the fantastic history and science behind some of the most dramatic landscapes on Earth.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus