Rough Sea-Slug Sex May Have Benefits

The bizarre mating behavior of hermaphroditic sea slugs — which involves stabbing penile appendages and hook-like penis spines — may have hidden benefits despite its wear on the body, new research finds.

Sea slugs that mate more than the absolute minimum necessary to retain female fertility are more fecund than slugs that mate less often, according to the study detailed today (Aug. 22) in the open-access journal PLoS ONE. The findings suggest that there are benefits to mating more than strictly necessary, even when the mating comes at a cost.

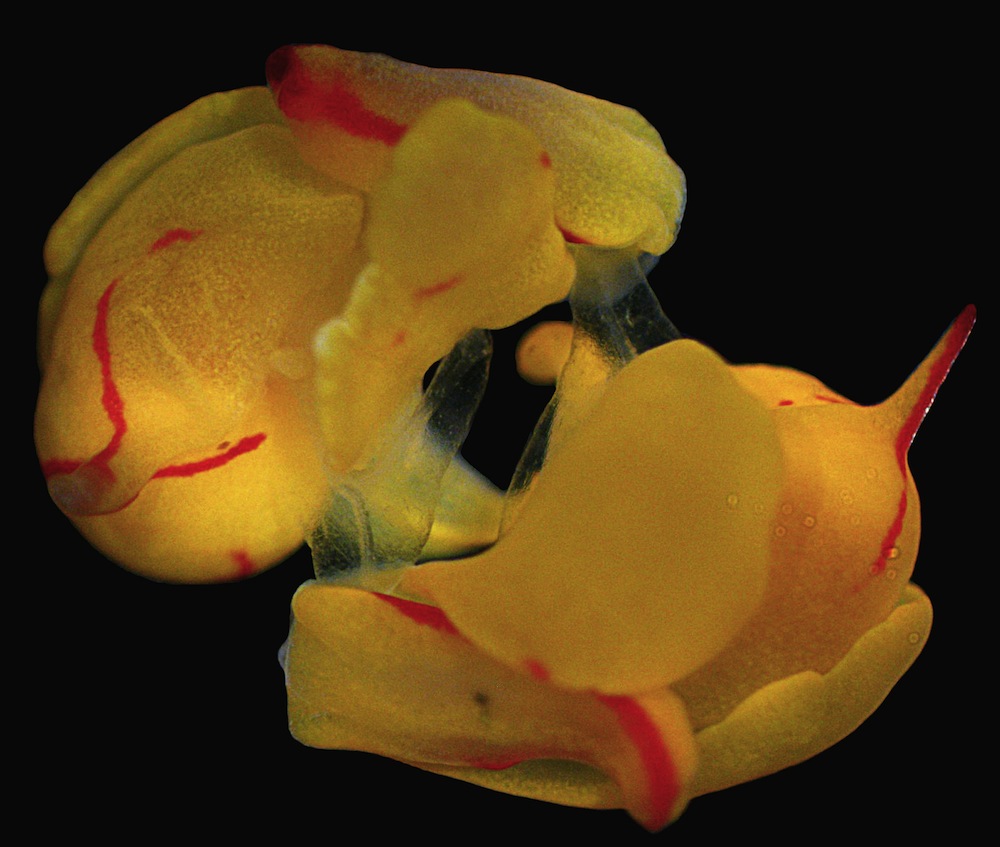

The brightly-colored sea slug Siphopteron quadrispinosum is hermaphroditic, meaning that individuals have both female and male genitalia. When mating, the slug playing the role of the "male" will stab its partner with a syringelike penile appendage and inject prostate fluids into the body. The sea slug penis also comes equipped with four to five large hooks on its base and 20 to 30 tiny spines on its tip, which anchor it into the female reproductive system.

Given all these pointy bits, sea slug sex can do a number on the receptive partner (in about half of matings, one slug takes the male and one the female role; in the other half, both simultaneously fertilize one another). But these slugs take on the female sexual role once or twice a day, researchers from the University of Tuebingen in Germany noticed, far more than necessary to keep the female system in working order. [Marine Marvels: Spectacular Photos of Sea Creatures]

To find out why, the researchers collected S. quadrispinosum from Lizard Island off of Queensland, Australia, and divided them into groups of four. Some of these groups were put together and given the opportunity to mate once every three days, less frequently than they mate in the wild. Another group was given one mating opportunity per day, about their natural rate. Finally, the third batch of slugs were given three mating opportunities a day.

The researchers then counted the resulting slug eggs. They found that the moderate-mating group was the most fecund of all three. Mating less decreased egg count by 23 percent. Mating more often decreased egg count by 10 percent.

It's possible that the once-every-three-days group just didn't have enough stimulation or sperm to reach their reproductive potential, the researchers wrote. On the other hand, the slugs that mated three times a day may have been overwhelmed by their sex-related injuries and thus had fewer resources to produce offspring. Or perhaps sea slugs given lots of chances to mate redirected their resources to producing sperm, rather than eggs.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The fact that moderate maters did best suggests that sea slugs try to balance the costs of their rough sex lives with whatever benefits come from mating more frequently. Multiple doses of sperm could allow the receiving partner to be choosy about which sperm fertilize the eggs, for example. Or sea slugs receiving sperm from multiple partners might be able to fertilize multiple-daddy batches of eggs, making it more likely that some offspring will survive no matter the conditions.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.