Human-Size Blob Drifts by Divers. And It's Packed with Hundreds of Thousands of Baby Squid.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

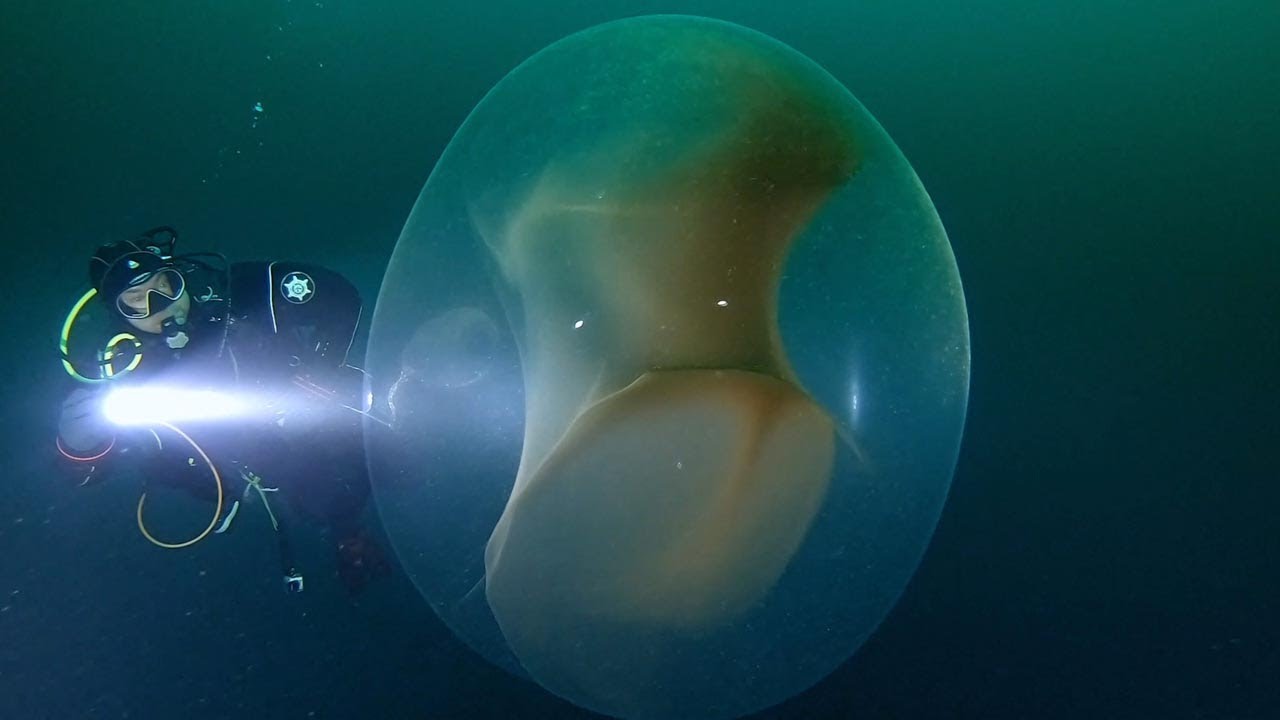

A trio of divers off the western coast of Norway had a close encounter with a drifting gelatinous blob — a squid's egg sac as big as an adult human.

A video captured and shared on YouTube on Oct. 6 by Ronald Raasch, a diver with the Norwegian research vessel REV Ocean, shows a diver slowly circling a spherical blob surrounded by a transparent membrane, with a dark mass suspended inside.

As the diver swam around the blob, his flashlight lit up its interior. Inside were numerous tiny spheres — eggs holding baby squid, estimated to number in the hundreds of thousands, according to the video description.

Related: Watch Rare Footage of Whales Blowing 'Bubble Nets' to Capture Prey in a Vortex of Doom

The REV Ocean divers spotted the egg mass during a visit to a submerged World War II shipwreck in Ørstafjorden, Norway, located about 650 feet (200 meters) from the coast. They were swimming back to shore at a depth of 55 feet (17 m) when they saw the blob drifting by, according to the YouTube description.

Raasch described the blob as a "blekksprutgeleball" — "squid gel ball" in Norwegian — when he posted the video. And this was far from the first account of such an unusual object. Dozens of similar blobs have been sighted in waters near Norway, Spain, France and Italy, with reports dating back 30 years, said Halldis Ringvold, a researcher with Sea Snack Norway and the project leader for "Huge Spheres," an investigation of the spherical sacs.

Scientists were previously perplexed by the blobs, which are so delicate that they are difficult to approach closely and sample for testing, Live Science previously reported. Divers had reported seeing spheres along the Mediterranean and Norwegian coasts in 2017, and DNA analysis of samples from four spheres recently confirmed that they were egg sacs belonging to the southern shortfin squid (Illex coindetii), a 10-armed cephalopod found on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, Ringvold told Live Science in an email.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The newfound sphere is similar to previously documented egg sacs in its appearance, size and location, "and I assume this is also made by Illex coindetii," Ringvold said. While the blob in the video appears to be about the same size as the diver swimming around it, these spheres typically measure about 3 feet (1 m) in diameter on average, Ringvold said in a statement.

"The dark mass is probably ink from the female squid, who injected it while making the sphere," he said. "At the very end of the video, it is possible to see the actual squid eggs. They are very small, round and transparent."

A shortfin squid egg measures about 0.07 inches (0.2 centimeters) in diameter when the embryo is ready to hatch, and females produce between 50,000 and 200,000 eggs, according to SeaLifeBase, an internationally managed database of marine life. Embryonic development typically takes 10 to 14 days when the water temperature is 59 degrees Fahrenheit (15 degrees Celsius), SeaLifeBase says.

The shortfin squid is part of the group Oegopsida, which is known to produce large, spherical egg sacs, Ringvold told Live Science. But for some species in this group, evidence of their egg masses is yet to be found. Researchers with the Huge Spheres project are therefore collecting photos and videos of sphere sightings, as well as tissue samples, to learn more about these elusive animals, Ringvold said in the email.

- Underwater Photos: Elusive Octopus Squid 'Smiles' for the Camera

- In Photos: Spooky Deep-Sea Creatures

- Gallery: Jaw-Dropping Images of Life Under the Sea

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus