Tasmanian Tiger Was Genetically Doomed

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Even if humans hadn't hunted the Tasmanian tiger to extinction, its low genetic diversity may have naturally doomed the curious marsupial, researchers have found.

"We found that the thylacine had even less genetic diversity than the Tasmanian devil," study researcher Andrew Pask, of the University of Connecticut, said in a statement. "If they were still be around today, they'd be at a severe risk, just like the devil."

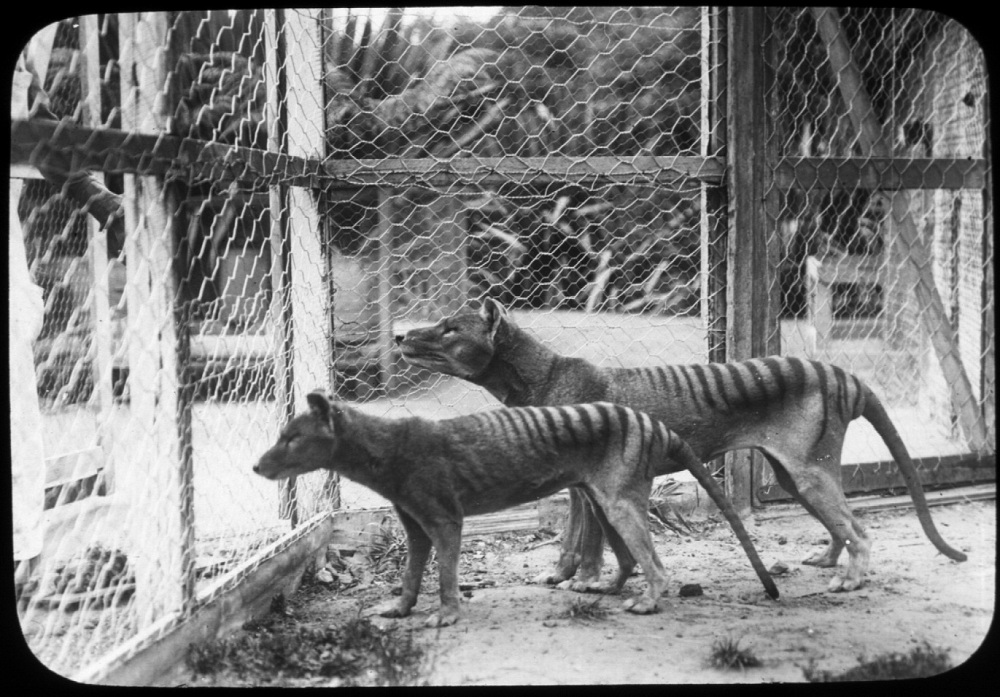

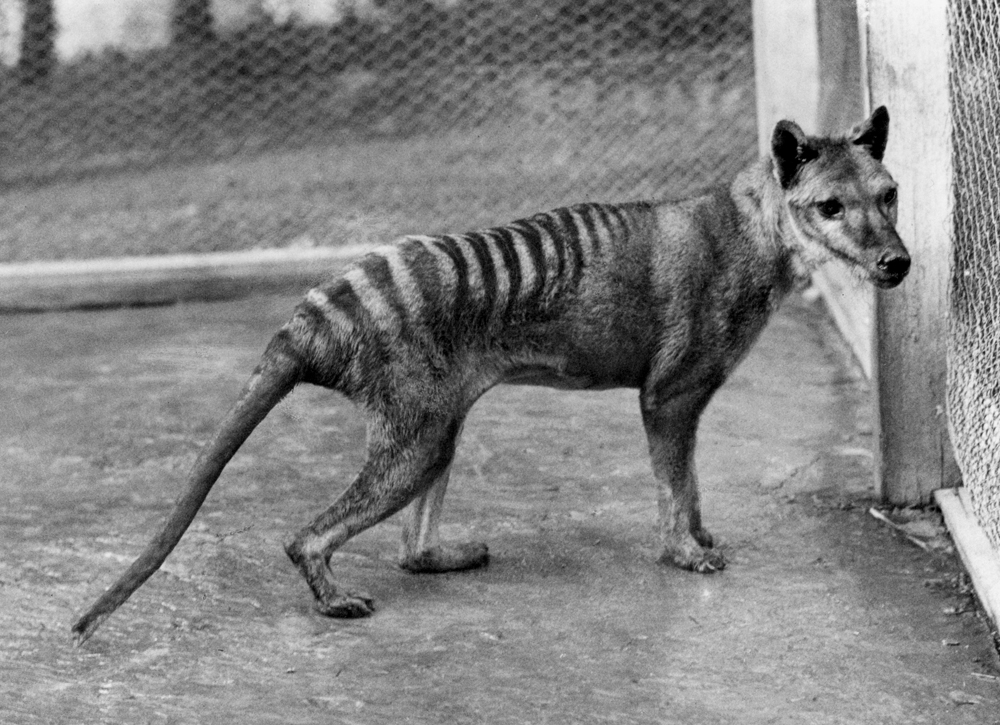

The Tasmanian tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus), also known as the thylacine, was hunted to extinction in the early 1900s; the last one died in a Tasmanian zoo in 1936. Named for its telltale stripes, the Tasmanian tiger stood as tall as a medium-size dog and once roamed across both mainland Australia and Tasmania. [Marsupial Gallery: A Pouchful of Cute]

The new research captured some genetic fragments from the Tasmanian tiger, from 14 samples including pelts, bones and preserved specimens more than 100 years old. The scientists found the individuals to be 99.5 percent similar over a portion of the genome that normally has lots of differences.

"If we compare this same section of DNA, the Tasmanian Tiger only averages one DNA difference between individuals, whereas the dog, for example has about five to six differences between individuals," study researcher Brandon Menzies, also of the University of Connecticut, said in a statement.

Genetic variability is basically the difference in the gene sequence between any two individuals. Analysis of the recovered genome indicates that the animal would have had too little genetic variability to survive. When this gets low, it spells doom for a species, because the species has more difficulty adapting to threats if it doesn't have a greater pool of genes to pull from.

Low genetic diversity can arise from many different situations: when a species consisting of many small isolated populations sees a precipitous drop in numbers or goes through a lot of inbreeding. In the case of the Tasmanian devil and the Tasmanian tiger, their low genetic diversity probably came from small groups that remained isolated from the main population in mainland Australia.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The tiger's extant cousin, the Tasmanian devil, is currently being decimated by a contagious cancer. The researchers say the devil's low genetic diversity allowed this disease to spread all the easier. The Tasmanian tiger, if around today, would also be exceptionally susceptible to diseases, the researchers said.

Knowing more about the Tasmanian tiger can help researchers fight for the still-living native species, like the Tasmanian devil. "From a conservation standpoint, we need to know these things about animals' genomes," Pask said. "There are a lot of fragile animals in Australia and Tasmania."

The study was published today (April 18) in the journal PLoS ONE.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter, on Google+ or on Facebook. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus