The Mind Makes Gunmen Look Larger

With gun in hand, a man of any size appears bigger, an altered notion that probably occurs at a subconscious level, a new study suggests.

The research, funded by the U.S. Air Force, reveals a seemingly simple mechanism that was even in the brains of Neanderthals, and possibly common even to chimpanzees, to measure whether they would win or lose a fight with an aggressor.

"There's nothing about the knowledge that gunpowder makes lead bullets fly through the air at damage-causing speeds that should make you think that a gun-bearer is bigger or stronger, yet you do," lead study author Daniel Fessler, an associate professor of anthropology at UCLA, said in a statement. "Danger really does loom large — in our minds."

Holding hands

Fessler, who is director of UCLA's center for behavior, evolution, and culture, and his colleagues ran several tests in which participants were asked to estimate the height of men based on photos of their hand, which was holding one of various objects, including a handgun. In some of the tests, participants also rated the object holder's overall size and muscularity based on a scale of six photos showing men with progressively more muscular bodies.

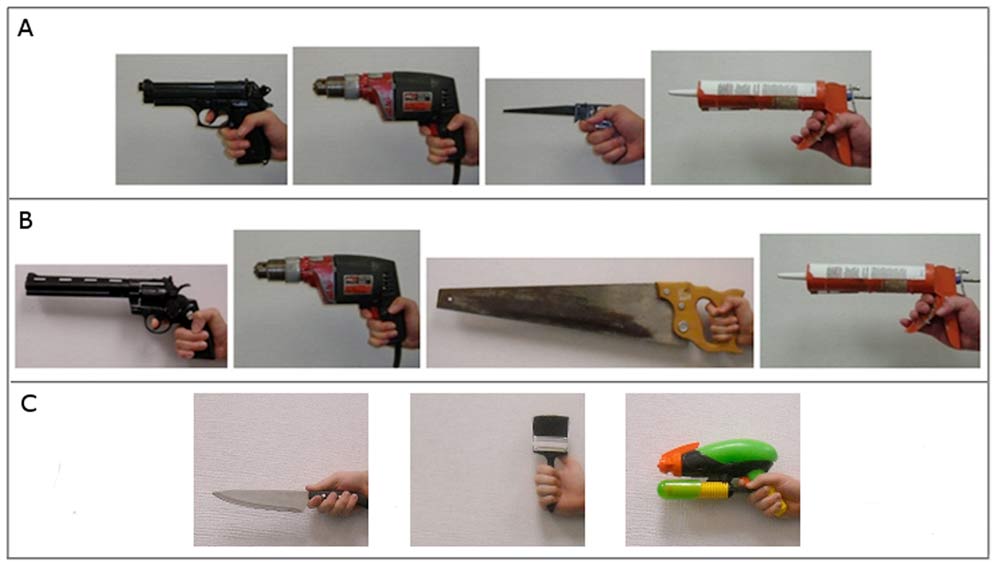

In one test, participants looked at four photos of different hands, each holding one of four objects: a caulking gun, electric drill, large saw, or handgun. [Infographic: US Gun Ownership]

Participants judged the gun-holders, on average, to be 17 percent taller and stronger than those rated as the smallest and weakest men, which in this test ended up being those holding caulking guns. Hand models holding the saw and drill were judged as the second and third, respectively, in terms of size and strength.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

(The test involved 628 participants, 497 of them female, and averaging 34 years old. To get a sense of participants' sizing accuracy, the researchers also had them do the same height estimation for images of progressively taller men as well as a set of images showing progressively more-muscular men.)

Perhaps the phenomenon had to do with the fact that in pop culture guns are usually associated with bulky men (think Rambo or Arnold Schwarzenegger). To find out, the researchers ran the same test but this time showed hands holding a kitchen knife (a stereotypically female object), a paintbrush (a stereotypically male but benign object) or a toy squirt gun.

On average, the 541 participants in this test judged the men holding the most lethal object, the knife, as the biggest and strongest of the bunch, followed by those holding the paintbrush and the squirt gun.

"It's not Dirty Harry's or Rambo's handgun — it's just a kitchen knife, but it's still deadly," study researcher Colin Holbrook, UCLA postdoctoral scholar in anthropology, said in a statement.

Neanderthal mental mechanism

The researchers concluded that the results of the study can be explained neither by such factors as real-world associations between body size and guns — gun owners aren't taller than non-gun owners — nor by cultural associations. Rather, they suggest a mental mechanism in a distant ancestor was modified through the years and still exists today.

"In a species with a complex behavioral repertoire like our own, when two parties come into potential conflict there are many different features that can contribute to the likelihood that one side or another will win," including size of the individual, level of coordination within a coalition, and possession of weapons, among others, Fessler told LiveScience,

Fessler and his colleagues are proposing that one way the human mind might make sense of all of these variables, in a way that would allow a quick decision (to fight, retreat or negotiate), is to have a visual representation of an individual or group's formidability. In the mind, this formidability would be represented by size. [10 Mysteries of the Mind ]

"Every time you have a new piece of information that tells you how dangerous that other party is relative to yourself, you update the picture by either enlarging it to make them seem [more muscular] or shrinking it and making them seem smaller and less muscular in the mind's eye," Fessler said.

The study, detailed online today (April 12) in the open-access journal PLoS ONE, is part of larger project funded by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research to understand how people make decisions in situations of potential aggression.

While this work someday could have practical implications for military strategies, in the near future the research is more about understanding complicated humans. "This is a first step in what we hope will be a number of investigations where the ultimate goal is to understand cognitive processes that underlie decision-making in situations of potential aggression," Fessler said during a phone interview.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.