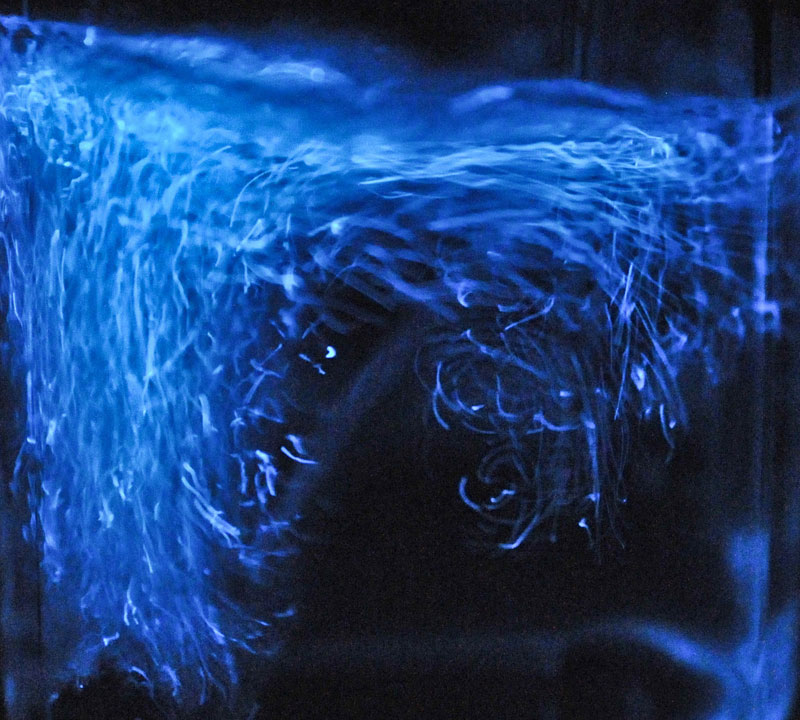

Living Light: How and Why Organisms Glow

NEW YORK — Some living things can light up dark places without help from the sun.

While fireflies are the best-known bioluminescent creatures, other species of insect, fungi, bacteria, jellyfish and bony fish can also glow. They employ a chemical reaction to glow at night, caves or most frequently, the black depths of the ocean.

Bioluminescence is scattered within the tree of life — although no flowering plants and few animals with backbones possess this ability — and researchers believe the ability evolved independently many times. [A Glow in the Dark Gallery]

A new exhibit on bioluminescence at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City officially estimates bioluminescence has evolved at least 50 times, "probably many more," curators there say.

Among bony fishes alone, the ability to produce light, sometimes with help from glowing bacteria, has evolved probably 20 to 30 times among different groups, according to John Sparks, curator in charge of the ichthyology department at the museum.

"Even with fishes, we know that these were all independent events, because there's different chemistries used by different groups. Some just [use] bacteria, some self-luminescent ones do it differently," Sparks told LiveScience.

Glow-in-the-dark organisms use variations on a chemical reaction that involves at least three ingredients: an enzyme called luciferase, which helps oxygen bind to an organic molecule (the third ingredient), called luciferin. The high-energy molecule created by the reaction releases energy in the form of light.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For organisms that do it, bioluminescence has many uses, according to the exhibit materials. Fireflies use flash to attract mates and to warn predators of the toxins they contain. Deep-sea anglerfish use a lighted lure to attract prey. The stomach lights on ponyfish evolved as a sort of camouflage to help them blend in with light filtering down from above. Dinoflagellates — the single-celled protists behind red tides — light up when disturbed, perhaps to startle predators or to attract creatures that eat their predators. Click beetles appear to use light to make themselves seem larger. Fungus gnat larvae glow to attract prey to sticky fishing lines that resemble bead necklaces. Vampire squid squirt out clouds of light to confuse predators.

Most bioluminescent organisms, about 80 percent of species, live in the most vast habitat on the planet — the deep sea. In fact, it is estimated that most species below 2,297 feet (700 meters) can produce their own light.

There's no consensus on why the ability to produce light has evolved so many times, but one theory has gained traction for life in the deep sea, according to Sparks.

"Luciferins, these light-producing molecules, are all good antioxidants, so it is thought that they may have been around as antioxidants, then, over time, they were co-opted for signaling," Sparks said.

As the oxygen content of the oceans increased, animals moved into deeper waters, out of the reach of harmful ultraviolet radiation. In the deep water, where the antioxidants were no longer needed to repair genetic damage caused by UV radiation, luciferins became the basis for a light-producing system, he said.

Not everything that glows is bioluminescent. Some organisms, such as corals, fluoresce, meaning they absorb light at one wavelength, such as UV radiation, and emit it at another wavelength. Since UV light isn't visible to the human eye, these creatures can appear to produce their own light.

The exhibit "Creatures of Light: Nature's Bioluminescence" opens at the American Museum of Natural History on Saturday (March 31) and is scheduled to run until Jan. 6, 2013.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.