Mysterious, Massive Black Holes Grew Fast by Gas-Guzzling

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The universe's first supermassive black holes grew so fast by gobbling up a steady stream of cold gas, a new study suggests.

Researchers have long wondered what fueled the rapid growth of these huge black holes, which were already monsters shortly after the first galaxies came together. The new study, based on supercomputer simulations, may provide an answer — thin strands of cold gas flowing straight into the black holes' maws at breakneck speed.

"We didn't know they were going to show up," study co-author Rupert Croft, of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, said in a Dec. 12 statement. "It was amazing to measure their masses and go 'Wow! These are the exact right size and show up exactly at the right point in time.' It's a success story for the modern theory of cosmology."

Big black holes in the universe's youth Supermassive black holes are thought to sit at the center of most, if not all, galaxies, including our own Milky Way. They are mind-bogglingly gigantic; scientists recently discovered two that each hold about as much mass as 10 billion suns.

Supermassive black holes have existed since the universe's very early days, just 700 million years after the Big Bang, scientists say. (The universe is about 13.7 billion years old). That's surprisingly early, the researchers added, since the first stars and galaxies had just formed a few hundred million years before.

"The Sloan Digital Sky Survey found supermassive black holes at less than 1 billion years. They were the same size as today's most massive black holes, which are 13.6 billion years old," said lead author Tiziana Di Matteo, also of Carnegie Mellon. "It was a puzzle. Why do some black holes form so early when it takes the whole age of the universe for others to reach the same mass?" [Photos: Black Holes of the Universe]

Solving the puzzle

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

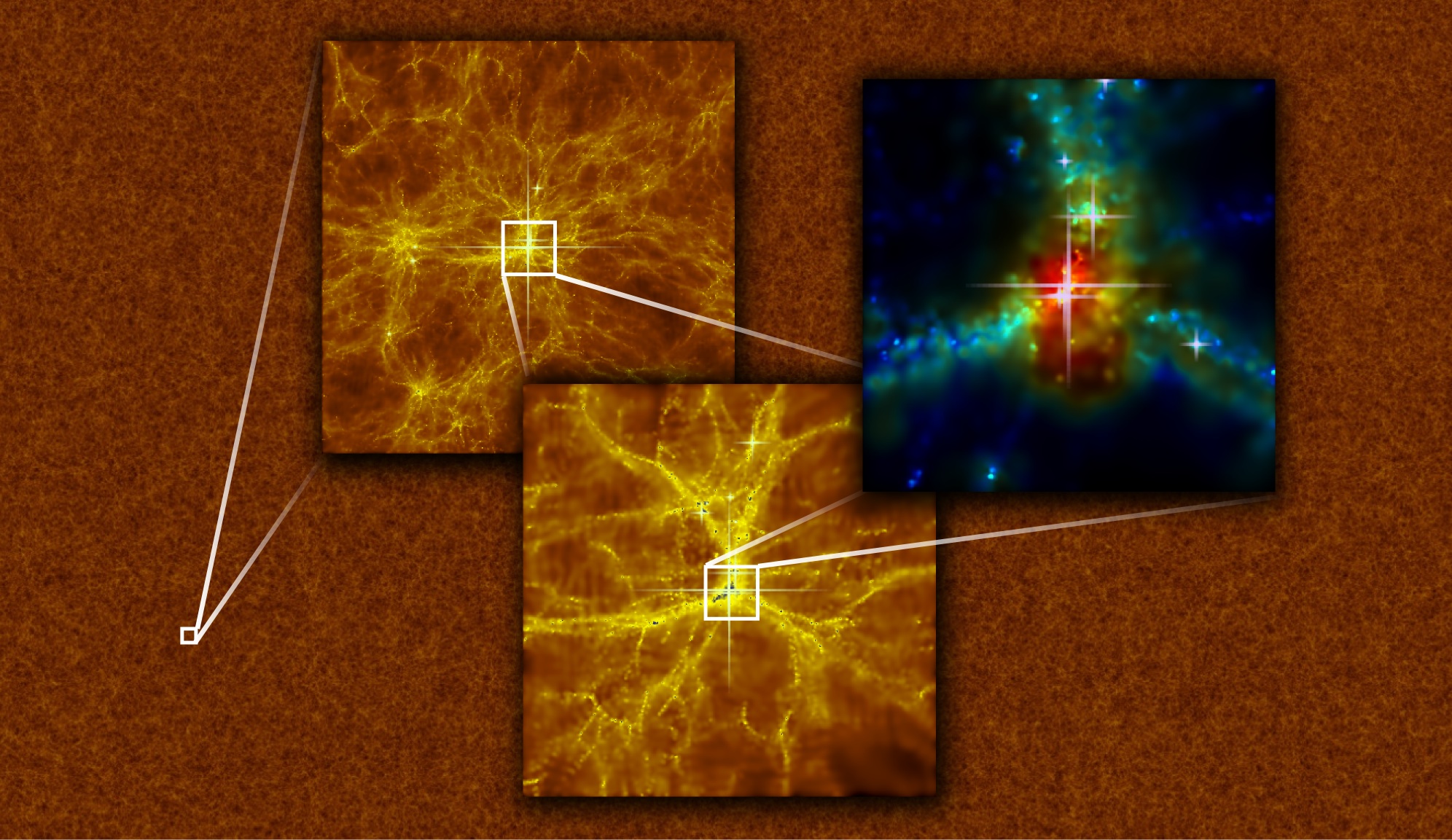

Di Matteo and her colleagues wanted to solve this puzzle. So they used supercomputers to perform a large-scale cosmological simulation that re-created the first billion years after the Big Bang.

"This simulation is truly gigantic. It's the largest in terms of the level of physics and the actual volume," Di Matteo said. "We did that because we were interested in looking at rare things in the universe, like the first black holes. Because they are so rare, you need to search over a large volume of space."

Normally, when cold gas flows toward a black hole, it collides with other gas in the surrounding galaxy, causing it to heat up before entering the black hole. This process, caused shock heating, puts the brakes on black hole growth somewhat.

But the team's simulations suggested that early supermassive black holes encountered no such check on their growth. Rather, streams of cold gas were likely channeled straight into their gullets along the filaments that give structure to the universe, causing the black holes to grow faster than anything in the early universe, researchers said.

The findings will be published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus