Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

MOFFETT FIELD, Calif. — The new haul of potential alien planets raked in by NASA's Kepler space telescope likely won't be the instrument's last big batch of discoveries, researchers say.

On Monday (Dec. 5), scientists announced that Kepler had detected 1,094 new exoplanet candidates, bringing the telescope's total discovery tally to 2,326 possible alien worlds. And it wouldn't be a shock if Kepler delivered more big numbers before the end of its prime mission in November 2012, researchers said.

"I think that we're going to have at least one more batch that's going to be a marked increase," Natalie Batalha, Kepler deputy science team lead at NASA's Ames Research Center, said here Monday during the Kepler Science Conference at Ames.

Hunting down alien planets

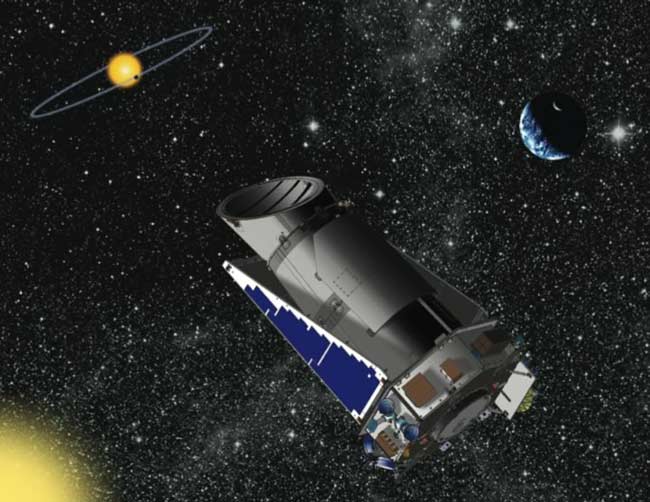

Kepler launched in March 2009 on a mission to find Earth-size planets in their parent stars' habitable zone — that just-right range of distances that could allow liquid water, and perhaps life as we know it, to exist. [Gallery: The Strangest Alien Planets]

The $600 million mission detects planets by what's called the transit method. The telescope watches for the tiny dips in brightness caused when a planet transits, or crosses in front of, its star's face from Kepler's perspective, blocking some of the star's light.

Kepler needs to observe three such transits to flag a potential alien world, which remains a "planet candidate" until follow-up observations — usually performed by large ground-based instruments — can confirm it.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Kepler's 2,326 candidates represent the telescope's discoveries in its first 16 months of observations, from May 2009 to September 2010. So far, about 30 of them have been confirmed, but researchers have estimated that at least 80 percent will end up being the real deal.

The tally should grow

The list of candidates is likely to jump considerably before Kepler's done. The telescope hasn't had enough time to witness three transits of some alien planets likely to be in the instrument's crosshairs, researchers say. It would take three years, after all, for a hypothetical alien Kepler spacecraft to see Earth transit our sun three times.

Also, mission scientists are continually improving their analysis software, and they recently made an upgrade that should increase their ability to spot small planets in the deluge of Kepler data, team members said.

"That's one example," Batalha said. "I think that that's going to give us another big haul this next time."

Kepler's prime mission, along with its funding, is set to end in November 2012. But the team is putting together a proposal to extend the telescope's operations for an additional four years or so. It currently costs about $20 million per year to operate Kepler and analyze its data, scientists have said.

There's no guarantee that NASA will re-up Kepler, especially since budgets are currently tight throughout most federal agencies.

But if Kepler's mission does get extended, the telescope could make many more finds far into the future. More time could allow Kepler to observe the required three transits for worlds that orbit relatively far from their host stars.

Seeing more transits would also increase the signal-to-noise ratio for closer-in planets, likely allowing more of them to be detected, researchers have said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus