Climate Success Story: Saving the Ozone Layer

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

SAN FRANCISCO — When nations agreed in 1987 to stop using chemicals that eat away at the protective ozone layer high in the atmosphere, they averted a great deal of hardship, said a senior NASA scientist.

In 1987, nations adopted the Montreal Protocol and agreed to phase out the production and use of so-called ozone-depleting substances. The benefits of this action are now on the horizon, according to atmospheric chemist Paul Newman, who offered a brief glimpse at a world without this treaty here at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU).

"Ozone-depleting substances are declining as we expected," Newman said. "The Montreal Protocol has led to that decline, and we expect them to continue to decline in the future."

Ozone levels are projected to return to 1980 levels by 2032, he said.

A scary future averted

In a world without the Montreal Protocol, two-thirds of the ozone layer would have been destroyed by 2065, and the UV index, a measure of the strength of the sun's ultraviolet rays, would have tripled, with the tropics seeing a particularly large increase in UV rays reaching Earth's surface.

The ozone layer is important, because it prevents harmful ultraviolet radiation from reaching the surface of the planet. To demonstrate the importance of ozone, Newman and his colleagues exposed a basil plant to the full solar spectrum of radiation, which includes UV rays, for 27 hours. A time-lapse video he showed during his presentation on Tuesday (Dec. 6) showed the plant's leaves turning brown and withering.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Increased UV exposure can lead to more sunburns, skin cancers, eye cancers, and as demonstrated with the basil plant, the loss of crops, as well as other problems. It could have one positive effect for people: increased vitamin D production, he said. (Vitamin D is produced in skin exposed to UV rays.)

So, a world without the Montreal Protocol would have meant more health problems, but that's not the worst of it, Newman said.

"If crop yields go down 10, 20, 30 percent, that would have had an enormous impact across the world in terms of food security," he said.

Ozone status

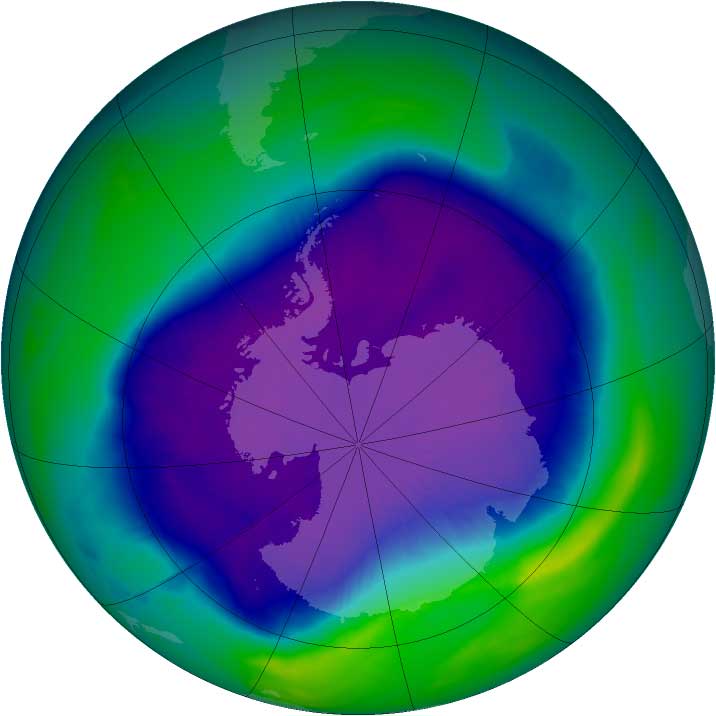

But though there has been progress, there's still a ways to go. The Antarctic ozone hole, a region above the chilly continent where protective ozone thins dramatically to create a "hole," still reappears annually; however, it is expected to recover later this century as the ozone-depleting substances still lingering in the atmosphere disappear. (The hole is not a complete absence of ozone, but rather an area with much smaller concentrations of the molecule.) The global ozone layer, too, is expected to recover around the middle of this century, he told the audience.

Thanks to unusually cold temperatures in the stratosphere and chlorine lingering in the stratosphere, the part of atmosphere where the ozone layer is located, the Arctic saw its first official ozone hole this spring. Although unprecedented in the Arctic, this phenomenon fit into the scientific understanding of ozone depletion, according to Newman, who worked on the most recent scientific assessment, done in 2010, for the Montreal Protocol.

Ozone-depleting substances are emitted by human activity at the planet's surface and eventually travel to the stratosphere, where there the chlorine atoms and certain other constituent parts break apart the three oxygen atoms that make up an ozone molecule. A single chlorine atom can destroy thousands of ozone molecules. [Earth's Atmosphere: Top to Bottom]

Thanks to the Montreal Protocol, the total chlorine released by ozone-depleting substances is declining in both the stratosphere and the lower atmosphere. Bromine, another ozone-destroying atom, is declining in the lower atmosphere and has stabilized higher up, according to the assessment.

Compounds consisting of hydrogen, chlorine, fluorine and carbon (HCFCs) have a lower potential to destroy ozone, but they are being used to temporarily replace CFCs and other ozone-depleting substances whose uses included aerosol propellants, refrigerants, foam-blowing agents and solvents.

HCFCs will eventually be replaced by substances called hydrofluorocarbons or HFCs, which do not destroy ozone at all.

Ozone depletion and climate change

There is a complex relationship between ozone loss and climate change. Ozone-depleting substances are also greenhouse gases, so the Montreal Protocol contributed significantly to international attempts to fighting global warming. However, since HFCs are also greenhouse gases, it's possible their increasing use could erase the benefit of phasing out ozone-depleting substances.

In addition, greenhouse gases can affect ozone cover, by affecting temperature in the stratosphere and by altering atmospheric circulation patterns in a way that changes the distribution of ozone over the planet, moving it away from the tropics.

As ozone-depleting substances disappear from the atmosphere, other greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide and methane, will become the most important factors determining ozone levels, Newman said.

You can follow LiveSciencesenior writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus