Turkey's Deadly Aftershock Explained

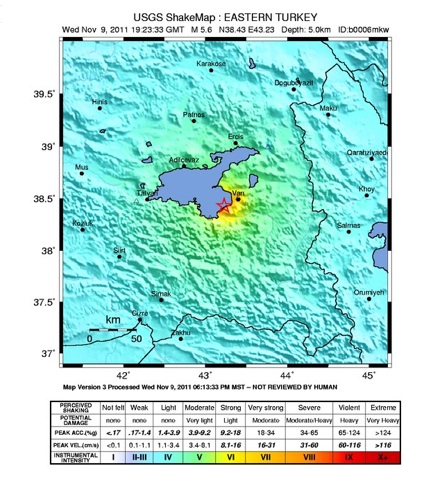

The magnitude 5.6 earthquake that struck Turkey yesterday (Nov. 9), killing eight people, was just the latest of the more than 1,000 of aftershocks to hit the region crippled by a powerful earthquake in late October, seismologists said.

Yesterday's quake was an aftershock of the magnitude 7.1 quake on Oct. 23 that killed hundreds in the eastern city of Van. Such a large aftershock is typical for such a strong earthquake, said seismologist Don Blakeman of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Golden, Colo.

"If we get something like magnitude 7, then we probably expect there will be at least one 6" aftershock, Blakeman told OurAmazingPlanet.

Destructive aftershock

Yesterday's quake ruptured 9 miles (14.5 kilometers) south of Van, collapsing a prominent hotel and burying an unknown number of people.

"There was dust everywhere and the hotel was flattened," Ozgur Gunes, a cameraman, told Sky Turk television.

Angry residents have begun protesting that many damaged buildings should have been shut down after the Oct. 23 quake, which destroyed about 2,000 buildings and weakened many others.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It doesn't take a lot more to bring them down," Blakeman said.

Turkey has seen about 1,400 aftershocks since the Oct. 23 quake, most of them small. The rule of thumb for aftershock strength is that the biggest aftershock will be about one magnitude smaller than the mainshock.

"The reason why that aftershock was so destructive is that its initial depth was very shallow and its epicenter was much closer to the city of Van," said Ross Stein of the USGS in Menlo Park, Calif., who has done work in the region.

Tectonically active area

Turkey is a tectonically complicated area, crisscrossed by fault lines and sandwiched between the Eurasian and Arabian tectonic plates.

"This Arabian plate is crashing into Turkey and causing the crust to stack up on itself," Stein said.

In the area of Lake Van and further east, tectonics are dominated by the Bitlis Suture Zone (in eastern Turkey) and Zagros fold and thrust belt (toward Iran), according to the USGS.

The Oct. 23 earthquake struck somewhere outside the eastern edge of the Anatolian block, where strike-slip faulting — a mechanism where fault systems slide side-to-side when two tectonic plates butt heads — is most common. That quake appears similar to those that occur on mapped faults east of the Anatolian block that have oblique-thrust faulting, a combination of side-to-side and up-and-down slipping. Yesterday's aftershock is of the thrust-faulting variety, Stein said, on an "off-fault" near the main rupture.

Turkey has seen several large quakes through the years. On Nov. 11, 1976, a magnitude 7.3 earthquake destroyed several villages near the Turkey and Iran border and killed thousands of people. A magnitude 7.8 earthquake struck Erzincan in 1939, killing an estimated 33,000 people.

As deadly as the Oct. 23 quake and its aftershocks have been, if the epicenter had been 6 to 12 miles (10 to 20 km) to the south, the quake would have more directly hit Van, and the damage would have been catastrophically worse, Stein said. [10 Deadliest Natural Disasters in History]

"By anybody's standards, it's a near-miss, Stein said. "This could easily have been a 10-to-50,000-death earthquake."

- 7 Most Dangerous Places on Earth

- Image Gallery: This Millennium's Destructive Earthquakes

- The 10 Biggest Earthquakes in History

You can follow OurAmazingPlanet staff writer Brett Israel on Twitter: @btisrael. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus