Turkey's Deadly Earthquake Explained

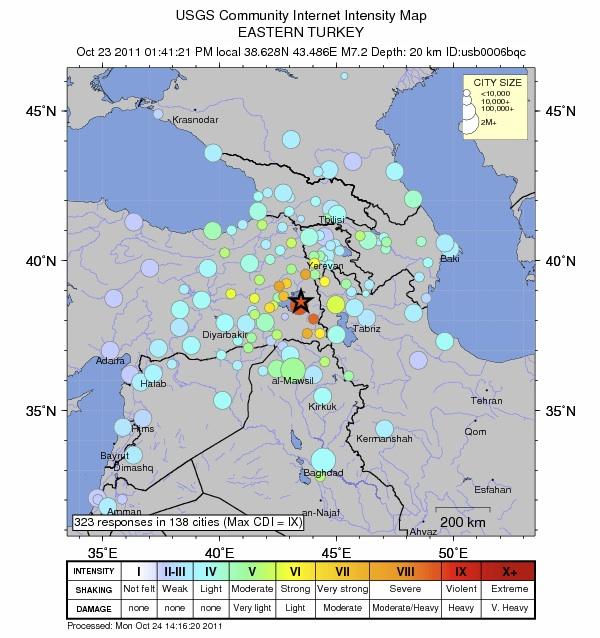

The magnitude 7.2 earthquake that rattled eastern Turkey on Sunday (Oct. 23) was a rare, powerful temblor for the area, but not entirely a surprise given the web of active faults in the region, earthquake scientists say.

Turkey rumbles often and has seen many destructive earthquakes throughout recorded history. The last major quake to strike the country was the Izmit earthquake of 1999, a magnitude 7.6 to the west of the Oct. 23 quake, which killed 17,000 people, injured 50,000 and left 500,000 homeless.

Magnitude 7 earthquakes don't happen very often in the area, but that doesn't mean it's surprising to see one there.

"We pretty much expect this sort of thing," said Don Blakeman, a geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Golden, Colo.

The Oct. 23 quake struck in the afternoon, about 9 miles (16 kilometers) north-northeast of the city of Van. The quake ruptured 12.4 miles (20 km) underground.

In Eastern Turkey, the Arabian Plate — a huge slab of the Earth's crust — is slowly smashing into the Eurasian Plate at a speed of less than 1 inch per year (24 millimeters per year). In Western and Central Turkey the movement is different, and the evidence of the country's complex tectonics is seen in the east-west running mountain range of western Turkey and the north-south mountains to the east, Blakeman said. What geophysicists call the Anatolian block is being squeezed by the converging Arabian and Eurasian plates.

"It's in a complicated area for sure," Blakeman told OurAmazingPlanet.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the area of Lake Van and further east, tectonics are dominated by the Bitlis Suture Zone (in eastern Turkey) and Zagros fold and thrust belt (toward Iran), according to the USGS.

The Oct. 23 earthquake struck somewhere outside the eastern edge of the Anatolian block, where strike-slip faulting — a mechanism where fault systems slide side-to-side when two tectonic plates butt heads — is most common. The quake appears similar to those that occur on mapped faults east of the Anatolian block that have oblique-thrust faulting, a combination of side-to-side and up-and-down slipping.

Regardless of the exact mechanism, the quake is just the latest to hit the country. On Nov. 11, 1976, a magnitude 7.3 earthquake destroyed several villages near the Turkey and Iran border and killed thousands of people. A magnitude 7.8 earthquake struck Erzincan in 1939, killing an estimated 33,000 people.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow OurAmazingPlanet staff writer Brett Israel on Twitter: @btisrael. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus