U.S. Rolls the Dice on Pharmaceutical Drug Innovation

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Pharmaceutical drug innovations have dried up in the U.S. over the past decade despite the government and private industry investing billions of dollars. Now federal officials hope a proposed $1 billion center can translate basic science discoveries into a new generation of drugs and therapies, if it survives the budget cuts in Congress.

Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and former head of the Human Genome Project, emphasized that the new center would not compete with pharmaceutical companies, during a teleconference on Feb. 23. It would reduce the risks and uncertainty for the most promising drug candidates before handing them off to companies.

"This is not an effort to turn NIH into a drug development company," Collins said. "The idea is to work with centers and institutes to move targets just far along for them to be attractive for commercial investment."

Pharmaceutical companies spent about $45.8 billion to "discover and develop new medicines" in 2009, according to the PhRMA industry website. But most of that money goes toward the late-stage human clinical trials, sales and marketing rather than rolling the dice on risky drug candidates, said Lesa Mitchell, vice president of advancing innovations for the Kauffman Foundation in Kansas City, Mo.

"Nobody wants to be in the business of Las Vegas science," Mitchell told InnovationNewsDaily.

Mitchell speaks from experience. She spent 20 years of her career in global executive roles for pharmaceutical companies such as Aventis and Quintiles before joining the Kauffman Foundation on its nonprofit mission to advance entrepreneurship.

The proposed National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) would combine many existing NIH programs that try to bridge the gap over the "Valley of Death" between basic science discoveries and innovations, and would also target funding toward universities or other institutions with a record of spinning off innovations.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

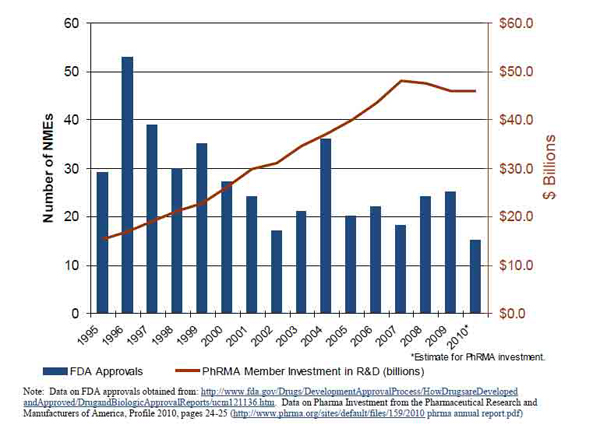

Urgency for such a center comes from the fact that the number of FDA-approved new molecular entities (drugs) have fallen off by close to 50 percent — from an average of 37 per year between 1995 and 1999 to an average of 21 per year between 2000 and 2010.

The innovation problem goes far beyond just spending more money or eliminating delays caused by regulatory red tape in the FDA, Mitchell explained. The falloff in newly approved drugs comes despite pharmaceutical company investments tripling since 1995, as well as NIH funding doubling between 1999 and 2003.

NCATS would aim to shake up the stagnation by looking beyond the new science discoveries that NIH already does well. Collins described its mission as one of "de-risk" that moves such discoveries beyond the lab and triages them to the point where private industry feels confident enough to jump in.

"If we can create incentives in terms of our grant making that is more focused about moving science to the market, people will look at their research and outcomes in a different way," Mitchell said.

This all assumes that the new center can survive the deeper budget cuts threatened by some members of Congress, and that Collins can push the changes through the NIH without running into too much bureaucratic red tape.

Mitchell voiced confidence in Collins, and added that it was crucial to get the new center up and running under President Obama's proposed 2012 budget. The recent economic recession may have curbed government and private industry appetite for simply throwing more money at the problem, but that creates a chance to approach innovation in a smarter way.

"The perfect storm is that we have no more money," Mitchell said. "We have a significant amount of GDP tied to our life science industry. And we're concerned about health care costs."

This article was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site of LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus