Face Shield for Soldiers Could Shield Brain, Too

Editor's Note: This article has been updated to reflect additional comment from researchers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, who disputed the characterization of their study by MIT's researcher.

When a roadside bomb blast hits an unprotected face, the pressure and the shear waves can squeeze the brain out of shape and cause tiny tears that disrupt brain connections built up over a lifetime. MIT's rocket scientists have teamed up with a brain-injury expert in the military to show that a face shield could block much of the blast waves, boosting protection for U.S. soldiers.

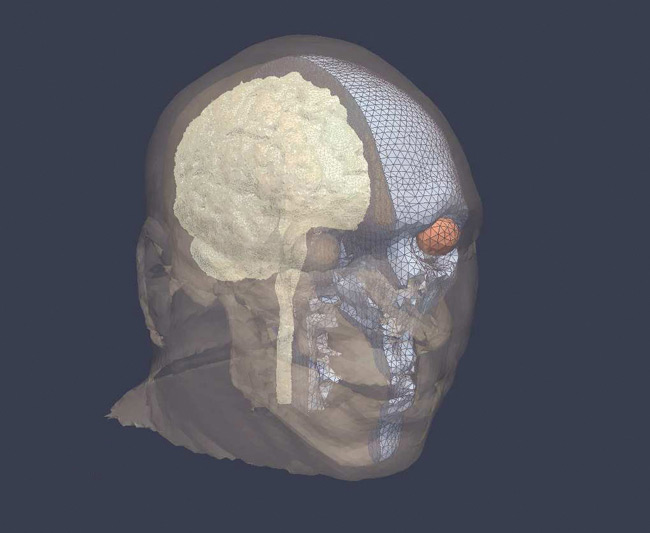

Brain simulations backed by field and lab blast tests showed how blast wave energy can easily reach the brain through the soft tissues of the face – the eyes and sinuses. A simulated face shield blocked that direct path for the blast wave and eliminated some of the stress waves that typically affect the brain.

"There's a passageway through those soft tissues directly into the brain tissue, without having to go through bone or anything hard," said Raul Radovitzky, an aeronautical engineer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Radovitzky and his colleagues also found that while existing Army helmets may not offer much protection against a frontal blast, wearing the helmet does not contribute to harming a soldier's brain in that scenario.

Better brain simulations

The MIT researchers built a sophisticated brain simulation by using a real person's brain scans. They also worked with David Moore, a leading neurologist at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, who studies brain injuries of military veterans.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Teaming up with the physician was very important," Radovitzky told LiveScience. "We're very good at digital reconstruction of geometry of the brain structures, and Dr. Moore helped us define all that."

The MIT simulation included details beyond the skull, such as spinal fluid, sinuses, eyes, gray and white brain matter, and many of the brain's internal structures. The researchers also simulated the Army's Advanced Combat Helmet (which its soldiers now wear) in detail.

The MIT team went a step further by checking its simulation against real-world tests. In an unpublished study, they modeled a pig brain based on an actual animal. They then rigged the model pig body with sensors and subjected it to blast tests in the lab and field

Full results are detailed in today's issue (Nov. 22) of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

A tale of two models

Radovitzky said that the findings challenge a study by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) from earlier this year. That study suggested an unpadded helmet could amplify the blast waves in the space between the skull and helmet – a phenomenon known as "underwash."

"The first key result of [our] paper is that the Livermore paper is wrong," Radovitzky said. "This helmet may not be helping much, at least for some blasts, but it's not true that it hurts."

But the Lawrence Livermore researchers said that Radovitzky missed the point of their study by focusing on the underwash finding in the case of an unpadded helmet. In fact, they had also run simulations that showed how a padded helmet can soak up some of the underwash. (The Army's current helmet has padding.)

"We weren't making a conclusion that a helmet can or can't address injury," said Michael King, a computational engineer at LLNL in California. "The main point is that helmets don't necessarily protect you [from blasts] – there's complex stuff going on whether you have pads or underwash."

The Lawrence Livermore researchers acknowledged that their simulation was simpler than the MIT brain simulation. But that's because they were focused on how the skull can flex in response to a blast wave, rather than on the internal brain.

How to protect the face

The MIT team is confident in its finding about the face shield protection. It tested a helmet with face protection, a regular helmet, and the absence of any helmet protection.

Just what form or shape the face shield should take remains open for discussion, but the MIT researchers have talked with the Army's Natick, Mass., laboratory, which develops equipment and other supplies for soldiers. The Army researchers could help figure out how a face shield affects a soldier's ability to fight and operate without hurting his situational awareness in the field.

"We can get involved in design, but that's out of this article's consideration," Radovitzky said.

Another question is how a helmet-protected head might withstand blast waves from the side or back. Early unpublished results suggest the current Army helmet does offer protection from side blasts, Radovitzky said.

The MIT researchers are comparing their simulation results to the Navy's real-world blast tests involving dummy heads. Such heads replicate all the brain tissue and bone with ballistics gel and plastics; the MIT group modified its simulation to have similar material properties.

Beyond the direct blast

Such comparisons showed that the MIT brain simulation holds up well so far, Radovitzky said. That gives the team added confidence to try to answer more questions about how blasts can affect the brain more indirectly, through other parts of the body.

"One of the possible research directions is to consider indirect transmission pathways, and that means adding more of the human," Radovitzky said. "Not just the head and torso, but maybe more."

Both the MIT and Lawrence Livermore teams agree that much remains uncertain about how explosive blasts relate to traumatic brain injuries. Besides the possibility of indirect transmission of the blast to the brain through other parts of the body, there's the chance that a rotation of the head may be causing injury, rather than the direct force of the blast itself.

"It has not been established by anybody that the primary action of the blast on the skull or head or face is causing TBI," said William Moss, a physicist at LLNL.

Until those questions are answered, it would be dangerous to categorically state that helmets help or hurt in protecting soldiers against the force of a blast, the Lawrence Livermore researchers said.