10 fascinating findings about our human ancestors from 2021

We learned a lot about our ancestors in the last year.

Our human ancestors and relatives lived tens of thousands to millions of years ago, and we still have much to learn about their existence and abilities. In 2021, researchers investigated all kinds of clues, including ancient skulls that shed light on the evolution of Homo brains, bones from previously unknown Homo species and fossilized footprints that revealed just how early humans arrived in North America.

Here are 10 amazing discoveries about our human predecessors that scientists made in 2021.

Related: 10 things we learned about our human ancestors in 2020

1. Early humans had ape-like brains

Humans are pretty smart today, but that wasn't always the case. Early members of the genus Homo had ape-like brains; it wasn't until 1.7 million to 1.5 million years ago that we developed "advanced" brains, an April study in the journal Science found. In other words, it took more than 1 million years for the genus Homo to evolve advanced brains.

Researchers discovered this by analyzing the skull endocasts (the inside of the cranium where the brain sat) of ancient and modern humans, as well as our closest living relatives, the great apes. These analyses revealed that it took time for humans to develop the brain's frontal lobe, which processes complex cognitive tasks.

Read more: First 'Homo' species left Africa with ape-like brains

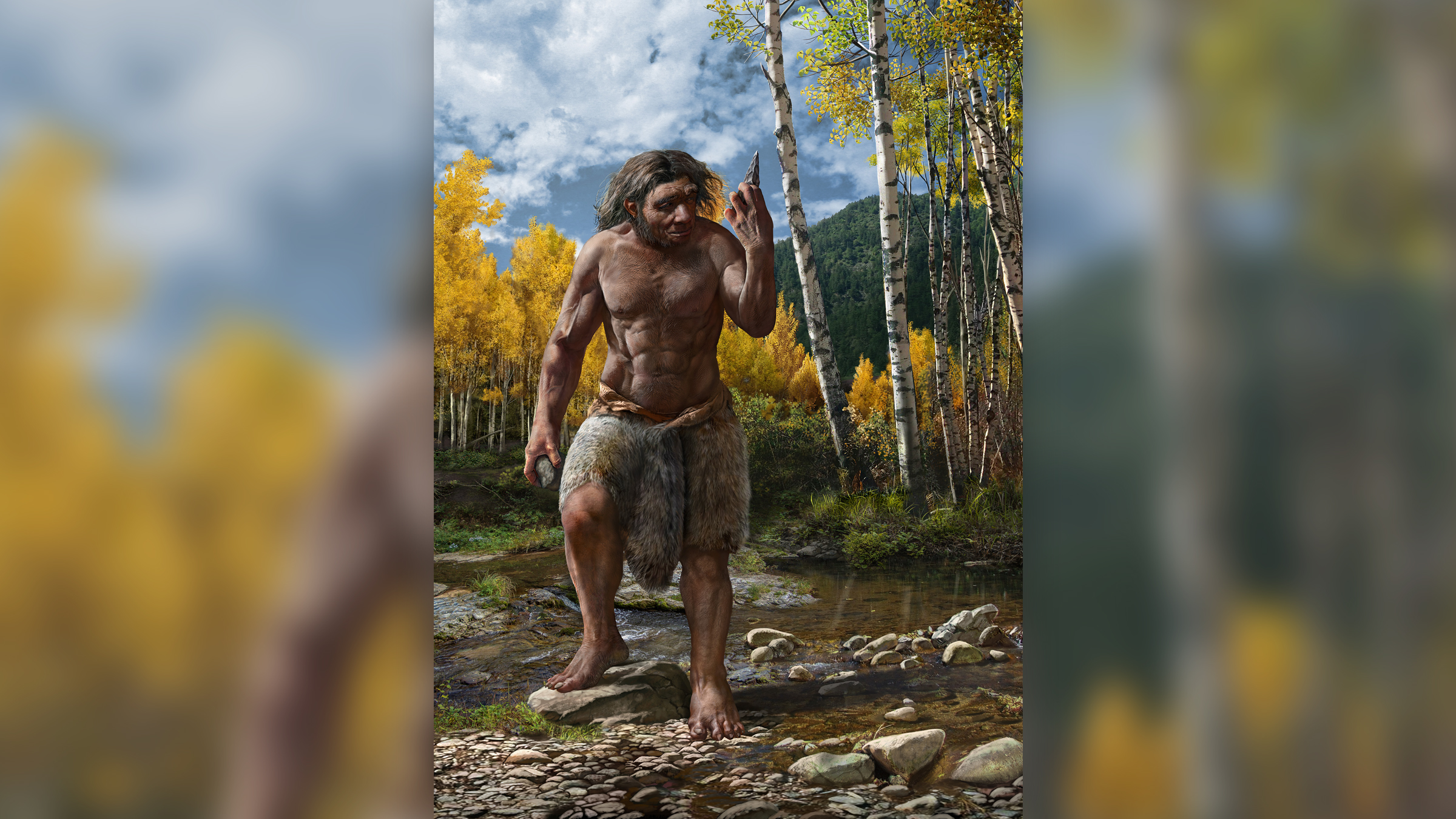

2. 'Dragon man' might be closer to us than Neanderthals

An ancient human skull found in China has led to the naming of a new species: Homo longi, or "Dragon man," according to three studies published in June in the journal The Innovation. This species might be our closest relative, even closer to us than the Neanderthals, who were previously considered to be our closest relatives. The roughly 146,000-year-old skull is the largest Homo skull on record and belongs to a man who died at about age 50.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, the finding is controversial. Three experts in human evolution, who were not involved in the study, all wondered whether Dragon man really belongs to the mysterious Denisovan human lineage.

Read more: New human species 'Dragon man' may be our closest relative

3. Ancient 'Child of Darkness' skull discovered in cave

How did the remains of a young Homo naledi child end up in a deep, narrow passageway in South Africa? Your guess is as good as ours. Scientists found the skull of the young child, whom they're calling "Leti," in the remote part of a cave system in what was possibly an intentional burial.

Leti lived between 335,000 and 241,000 years ago and is one of more than two dozen H. naledi individuals whose remains have been found in the cave system since 2013. These individuals have revealed that H. naledi walked upright, stood about 4 feet, 9 inches (1.44 meters) tall and weighed between 88 and 123 pounds (about 40 and 56 kilograms).

Read more: 240,000-year-old 'Child of Darkness' human ancestor discovered in narrow cave passageway

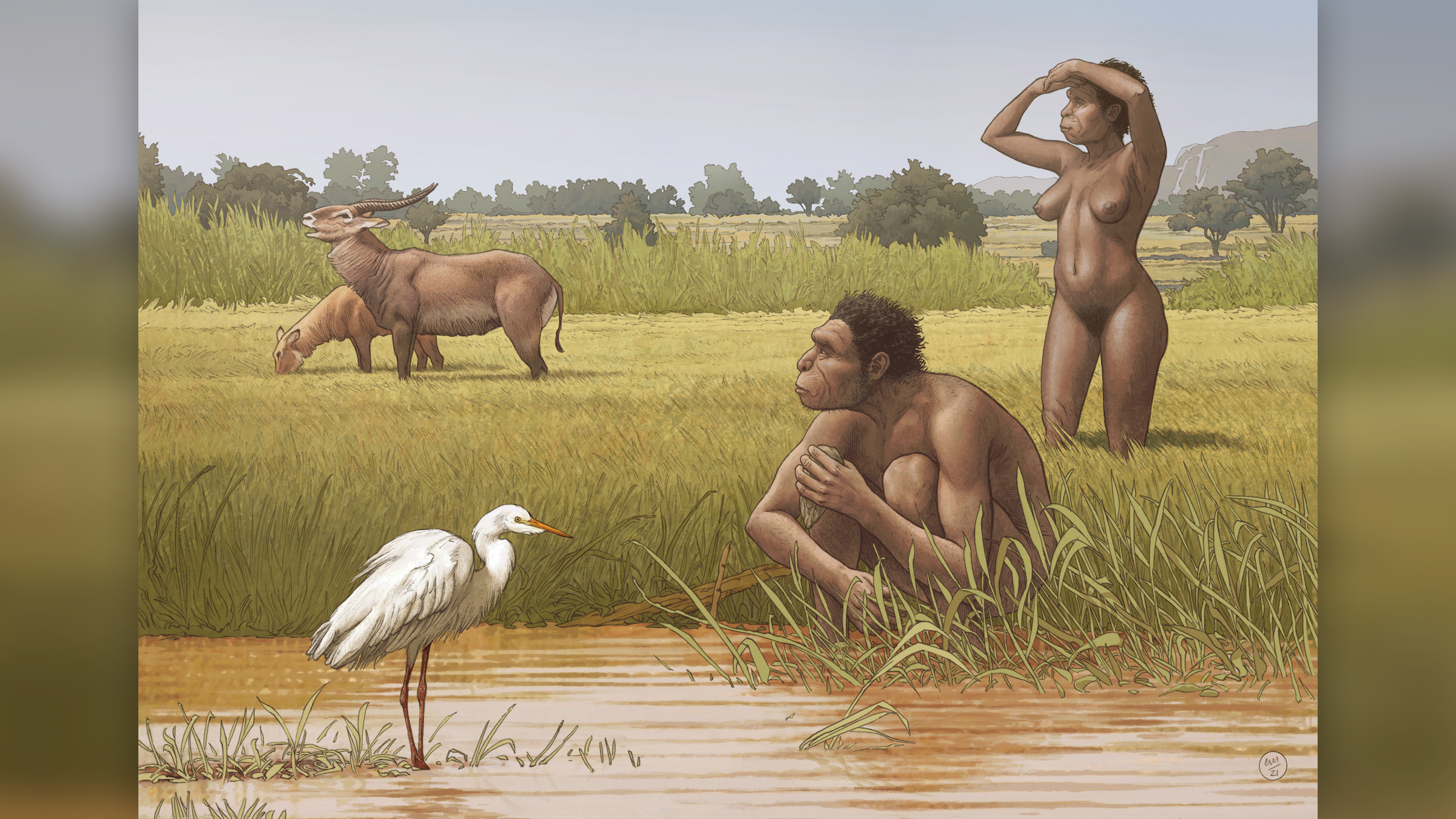

4. Meet a direct human ancestor: Homo bodoensis

A new analysis of a 600,000-year-old skull originally found in 1976 has revealed a new human species: Homo bodoensis, a possible direct ancestor of Homo sapiens. The discovery may help to disentangle how human lineages moved and interacted across the planet.

Researchers didn't simply rediscover the skull, however. Rather, they did a systematic review of human fossils dating from 774,000 to 129,000 years ago. A pile of evidence showed that the previously named species H. heidelbergensis and H. rhodesiensis were problematic. Now, H. heidelbergensis specimens may be reclassified as Neanderthals or H. bodoensis. Further study of Homo individuals from this time period may even reveal previously unknown species, according to the October study in the journal Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues News, and Reviews.

Read more: Newly named human species may be the direct ancestor of modern humans

5. Human burial reveals vanished lineage in Indonesia

Ancient human lineages don't always leave traces. But the discovery of a 7,200-year-old burial in Indonesia revealed a previously unknown human lineage that died out at some point. A genetic analysis of the ancient woman's remains showed that she is a distant relative of the Aboriginal Australians and Melanesians, or the Indigenous people on the islands of New Guinea and the western Pacific.

This woman had a significant proportion of DNA from an archaic human species known as the Denisovans, just like the Aboriginal Australians and New Guineans. So, perhaps Indonesia and the surrounding islands were a meeting point between modern humans and Denisovans, the researchers said in the study, published in August in the journal Nature.

Read more: Ancient remains found in Indonesia belong to a vanished human lineage

6. Oldest deliberate human burial in Africa happened 78,000 years ago

A young child was laid to rest deep in a cave in Kenya about 78,000 years ago, making it the oldest purposeful human burial in Africa on record. The 3-year-old child, nicknamed "Mtoto," which is Swahili for "child," was laid curled on their side, as if they were sleeping. Mtoto's head may have been placed on a cushion, the researchers found.

There are older-known burials of H. sapiens, including those dating to about 120,000 years ago in Europe and the Middle East, but Mtoto's remains are the earliest deliberate human burial known in Africa, according to the study, published in May in the journal Nature.

Read more: Oldest deliberate burial of a human in Africa discovered

7. Massive genome analysis reveals importance of Arabian Peninsula

The largest ever study of Arab genomes to date reveals just how key the Arabian Peninsula was to early humans migrating out of Africa. The study looked at the DNA of 6,218 Middle Eastern adults and compared it with the DNA of ancient and modern people from all over the world.

The analysis revealed that Middle Eastern groups made significant genetic contributions to European, South Asian and even South American communities, likely because as Islam spread across the world over the past 1,400 years, people of Middle Eastern descent interbred with those populations, the researchers said. What's more, the results indicated that the ancestors of the Arabian groups split from early Africans about 90,000 years ago, which is about the same time as the ancestors of Europeans and South Asians split from early Africans, the researchers found in the October study published in the journal Nature Communications. This discovery supports the idea that when early humans left Africa, they did so by traveling through Arabia.

Read more: Arabia was 'cornerstone' in early human migrations out of Africa, study suggests

8. Genes from 1st Americans match those from Australians

When one of the waves of first Americans crossed the Bering Land Bridge and entered North America during the last ice age, they carried something special in their genes: pieces of ancestral Australasian DNA. The Australasians are the Indigenous peoples from Australia, Melanesia, New Guinea and the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean.

These Australasian pieces of DNA are still present today, generations later, in Indigenous peoples in South America. However, not every Indigenous American group has this DNA; it appears that one of the waves of first Americans carried this DNA, while other waves didn't.

It's likely that there were coupling events between the ancestors of the first Americans and the ancestors of the Australasians in Beringia or perhaps even Siberia, according to the April study published in the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Read more: 1st Americans had Indigenous Australian genes

9. Oldest fossilized footprints found in the Americas

Exactly when the first Americans arrived during the last ice age is still a matter of debate. However, 60 footprints found in an ancient lake bed in White Sands National Park, New Mexico, date to between 23,00 to 21,000 years ago, a hint that people were here pretty early — far earlier than the roughly 13,000-year-old Clovis tools found years ago.

These footprints aren't the oldest evidence of humans in the Americas, but they are the first definitive proof that people lived here at the height of the Last Glacial Maximum, which lasted from 26,500 to 19,000 years ago, according to the September study, published in the journal Science.

Read more: Fossilized footprints in New Mexico are earliest 'unequivocal evidence' of people in the Americas

10. Oldest-known Denisovan fossils found

The oldest-known Denisovan fossils are about 200,000 years old, according to newly discovered bones found in a Siberian Cave.

The Denisovan might have once been widespread across continental Asia, according to research on DNA extracted from Denisovan fossils. But their remains are scarce. Until now, there were just six known Denisovan individuals — five from Denisova Cave in Siberia and one from China. With the new finding, researchers now have fossils from an additional three Denisovan individuals from Denisova Cave.

If researchers keep finding Denisovan remains, perhaps this enigmatic species won't be so mysterious to us in the future.

Read more: Oldest-known fossils of mysterious human lineage uncovered in Siberian cave

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.