Oldest deliberate burial of a human in Africa discovered

The tiny grave held the remains of a 3-year-old child.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

About 78,000 years ago, deep inside a cave near the coast of what is now Kenya, the body of a small child was carefully laid to rest in a tiny grave. Now, an international group of researchers has used advanced scientific techniques to peer into the past, revealing for the first time details of the ancient interment — finding that it is the oldest deliberate burial of a Homo sapiens individual in Africa.

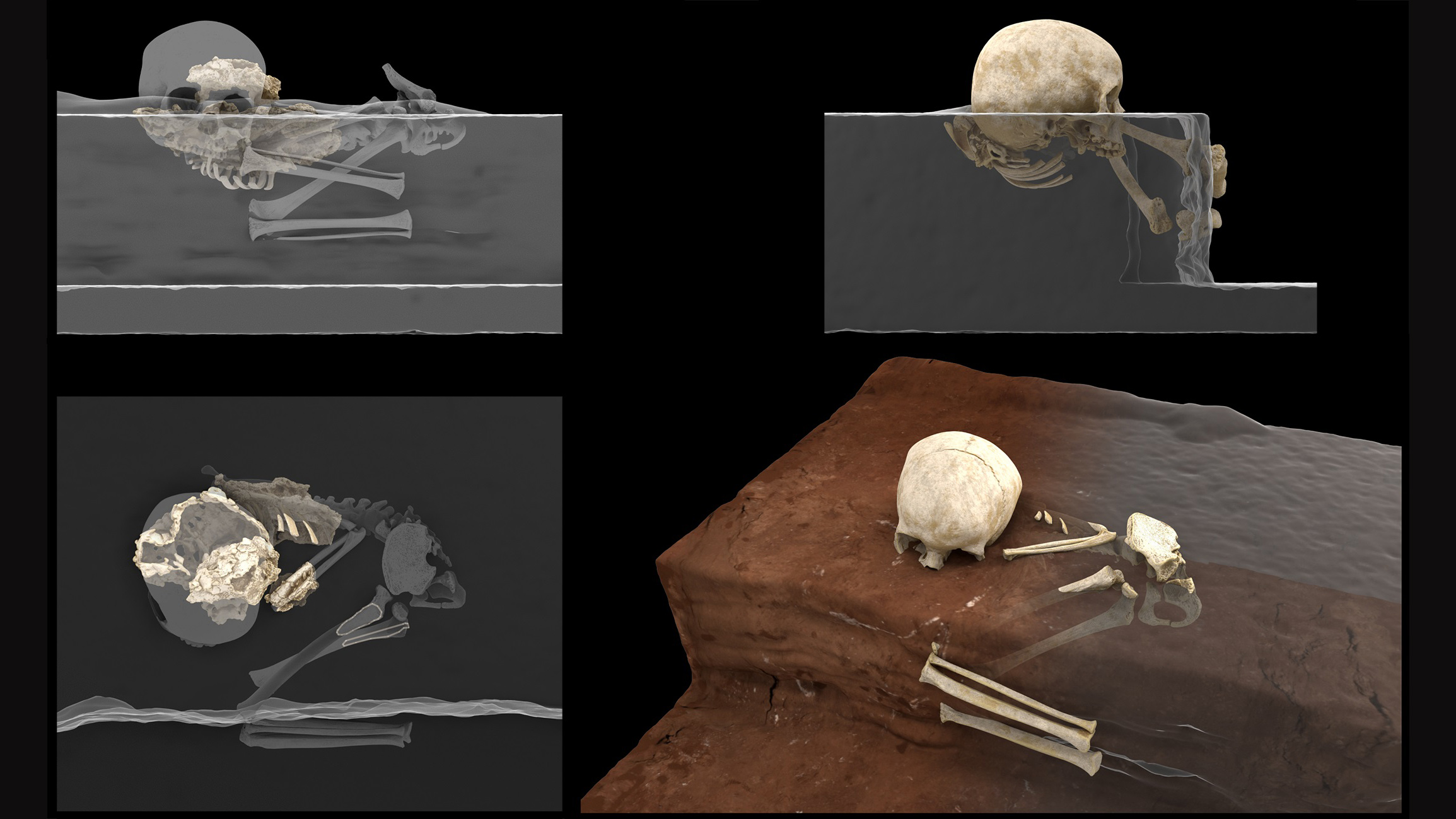

The child was only about 3 years old when they died. Their body was curled up on their side, as if to sleep or to keep warm, and the child's head seems to have been delicately placed on a rest or cushion. The scientists have named the remains "Mtoto," which is Swahili for "child."

Related: See photos of our closest human ancestor

"Only humans treat the dead with this respect, this care, this tenderness," said paleoanthropologist Maria Martinón-Torres, who led the team that first discovered the ancient burial. "This is some of the earliest evidence that we have in Africa about humans living in the physical and also in the symbolic world."

Martinón-Torres is the director of the National Center for Research on Human Evolution (CENIAH) in Burgos in Spain.

In 2017, after the grave was excavated from the Panga ya Saidi cave north of Mombasa, archaeologist Emmanuel Ndiema of the National Museums of Kenya carried it inside a block of sediment on a flight from Nairobi to Jena in Germany. From there, Martinón-Torres took it with her during a flight to Burgos.

The scientists knew the sediment block contained ancient bones of some sort, although it was very small. Months of intricate investigations by the CENIAH team, which included using micro-computed tomography (Micro-CT) to examine it with X-rays and create a detailed 3D model of its contents, revealed the skull and bones of a small Homo sapiens child.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ancient grave

Older Homo sapiens burials have been found in Europe and the Middle East, some dating to about 120,000 years ago.

But the remains of Mtoto, from about 78,000 years ago, are the oldest evidence of a deliberate burial found in Africa to date, said anthropologist Michael Petraglia of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena.

Petraglia helped excavate the sediment block from the Panga ya Saidi cave and is one of the authors of a study about the find, published Wednesday (May 5) in the journal Nature.

Petraglia said that the 40,000-year gap between the oldest-known Homo sapiens burials and Mtoto's burial probably reflected the fact that paleolithic archaeology was relatively recent in Africa compared to Europe and Asia, although Africa is the original home of our species and could have burials that are even older.

Some features of the Mtoto burial are similar to earlier burials by both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis), which were named after the Neander Valley in Germany where their fossils were first found.

Related: Photos: Squashed skull of 70,000-year-old Neanderthal discovered in cave

Ancient stone flakes and other evidence show that Panga ya Saidi cave was also used as a temporary residence by groups of Homo sapiens hunter-gatherers, and Neanderthal and Homo sapiens graves have also been found at similar "residential" sites in Eurasia, he said.

The researchers also found that a pit surrounding the child's body had been dug deliberately, showing that it was a true burial and not mere "funerary caching" of a dead body in an available niche, which is seen at some other ancient sites, Petraglia said.

Tender burial

Mtoto appeared to have been laid to rest with much care.

The body was shrouded in some perishable material and the child's head was distinctively tilted, which suggests that it was placed on a head rest of some sort that had since rotted away.

Mtoto was buried lying on their side, in a "flexed" position that was common in many ancient human societies, and which may have been seen as a natural way to place the dead, Martinón-Torres said during an online presentation this week.

Nicole Boivin, the director of archaeology at the Max Planck Institute in Jena, has worked at the Panga ya Saidi cave for about 10 years.

"It's an absolutely beautiful place — it's this cave system where parts of the roofs of the caves have collapsed, and this lets in sunshine … vines are falling in, and there are a lot of plants and flowers and wildlife," Boivin told Live Science.

Although the archaeologists had initially set out to look for traces of ancient burials and artifacts from the later period of early Indian Ocean trade (dating from up to 2,300 years ago), it soon became apparent that the cave had been an important place for much longer than that, Boivin said.

"We have representation of archaeology across an extraordinary time span," she said. "We have an extraordinary cultural record with beautiful stone tools, lots of material culture, symbolic artifacts [and] a lot of beautifully preserved bone."

Archaeologist Ndiema said that the Panga ya Saidi cave was considered a sacred place by some Kenyans today, as it probably was during the Stone Age.

"It still has a very strong cultural and spiritual connection with the local people. … They still use this place for rituals of worship and to seek healing," he said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Editor's note: This article was updated to delete a reference to "woven cloth," which wasn't invented until around 8,000 years ago.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus