Scientist Liked 'Story' Problems in Math as Kid

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Editor's Note: ScienceLives is an occasional series that puts scientists under the microscope to find out what makes them tick. The series is a cooperation between the National Science Foundation and LiveScience.

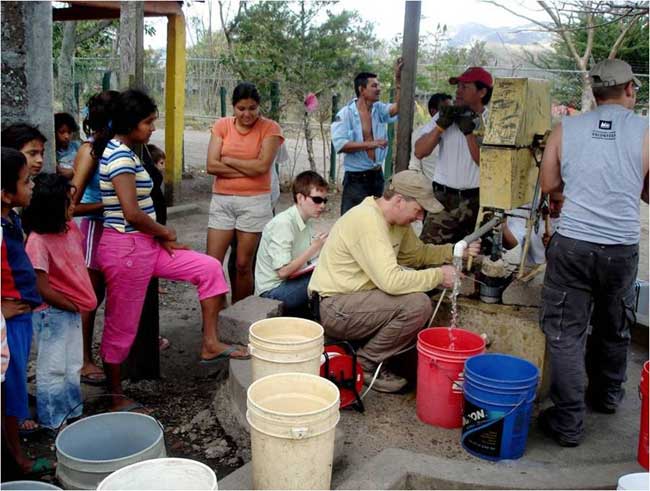

Profile Name: John Gierke Age: 46 Institution: Michigan Technological University Field of Study: Geological & Environmental Engineering Volcanic ground is a challenging place to drill water wells. In central Nicaragua, situated on volcanic bedrock, only three of every 10 wells drilled produce sufficient water for even one household because groundwater in volcanic rock flows primarily through fracture zones that can’t be seen from the surface. Locating those underground fractures can improve the well-drilling success rate dramatically. John Gierke of Michigan Technological University leads a National Science Foundation-funded research effort called Remote Sensing for Hazards Mitigation and Resource Protection in Latin America that helps address such needs such and develops remote sensing tools and validation methods for hazard mitigation and resource protection in Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Ecuador, Panama, and soon, Costa Rica. An upcoming Behind the Scenes story will feature the work, and Gierke’s former graduate student Jill Bruning, but as a prelude, Gierke answers the ScienceLives 10 questions below. What inspired you to choose this field of study? Early on in my junior high school education, I started to realize that I was skilled at solving mathematical problems, especially the dreaded "story" problems. These budding skills led me to prepare to study engineering. My concern for the natural environment led me to focus my undergraduate studies in environmental aspects of civil engineering. While I was undergraduate research assistant in the lab in my senior year of college, I assisted in studies of how pollutants move in groundwater, which led me to study subsurface problems thereafter. What is the best piece of advice you ever received? I cannot really say that this advice came from any one person, but a maxim derived from mentors over the years that I follow in research, teaching, and even diagnosing/fixing problems around my farm is: Break complex problems into parts that are small enough to be solved. What was your first scientific experiment as a child? I did pretty lame stuff, mostly trying to see how different household products killed weeds, which almost any chemical I used did. I did not realize at the time that weeds were not the real problem, but the chemicals we used to kill weeds were, or else I would have conducted different experiments. What is your favorite thing about being a scientist or researcher? I really enjoy figuring out how things work, especially in nature. What is the most important characteristic a scientist must demonstrate in order to be an effective scientist? Scientists must be objective. Although we may hypothesize a certain result, we must remain objective, and if the results suggest so, we must willingly accept that we initially guessed wrong. What are the societal benefits of your research? The majority of my work is related to water in the subsurface (aquifers), including ways to find it, produce it, clean it up when it is polluted, and prevent it from becoming polluted. I also like to think that in the conduct of research I have a positive influence on the development of new scientists and practicing engineers who provide benefits to society. Who has had the most influence on your thinking as a researcher? I can never be grateful enough to my graduate advisor, Neil Hutzler, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Michigan Tech, for giving me the opportunity to do research, starting as an undergraduate student and continuing through my Ph.D. I do not think that I would have pursued this path had it not been for him. Since then, practically all of my graduate students, especially those in doctoral studies, have continued to shape my research interests. What about your field or being a scientist do you think would surprise people the most? I know that I was surprised to learn how similar the approaches for studying problems, either experimentally or mathematically, are among many fields of science and engineering. For example, equations that describe heat and electrical conduction, chemical diffusion, and groundwater flow are identical in form, only the symbols used for the variables are different. This is really a tremendous benefit because it allows scientists in different fields to work together more easily and study complex, interdisciplinary problems. If you could only rescue one thing from your burning office or lab, what would it be? Everything in my office is either backed up, replaceable, or not worth replacing, so at the moment, I would probably grab an experiment that one of my students has going in the lab because it has taken her months to get the plants to grow and fabricate the sampling system, and she wants to finish soon. What music do you play most often in your lab or car? When I am not listening to NPR news or talk radio, which is rarely, I like to listen to Americana, like Slaid Cleaves.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus