Scientists Create World's Thinnest Balloon

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

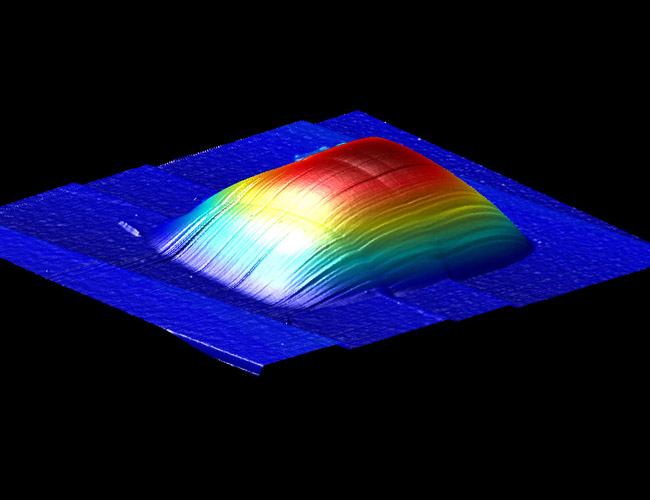

Scientists have created the world's thinnest balloon, made of a single layer of carbon just one atom thick.

The fabric that the balloon is made of is leakproof to even the tiniest airborne molecules. It could find use in "aquariums" smaller than a red blood cell, through which scientists could peer at molecules, researchers suggested.

The balloon is made of graphite, as found in pencils, which is made of atom-thin sheets of carbon stacked on top of each other known. The sheets are known as graphene.

Graphene is highly electrically conductive, and scientists are feverishly researching whether it could find use in advanced circuitry and other devices.

"We were studying little graphene trampolines, and by complete accident, we made a graphene sheet over a hole. Then we started studying it, and saw that it was trapping gas inside," said researcher Paul McEuen, a physicist at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y.

By experimenting further with bubbles made of graphene, McEuen and his colleagues found the membranes were impermeable to even the smallest gas molecules, including helium.

"It's amazing that something only an atom thick can be an impenetrable barrier. You can have gas on one side and vacuum or liquid on the other, and with a wall only one atom thick, nothing would go through it," McEuen told LiveScience.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In terms of applications, McEuen suggested one possibility which he called miniature aquariums for molecules. "You could have instruments on one side of the membrane, in vacuum or air, and on the other side you would have DNA or proteins suspended in liquid," he explained. "And then you could get right up close to image the molecules, within a few angstroms," or widths of an atom.

Other potential applications include hyper-fine sensors and ultra-pure filters.

"Once you have a membrane that won't let anything past, the most interesting thing is to then poke a hole in it. Then you can detect what leaks through that hole with high sensitivity, or make sure only what you want leaks through that hole," McEuen said.

The only way gas leaked out from inside the balloons was through the glass that the bubbles were anchored on, McEuen explained.

"We need to build a better base that's more impenetrable, such as single crystal silicon. I'm confident we can make a leakproof version," McEuen said.

The scientists will detail their findings in the Aug. 13 issue of the journal Nano Letters.

- TechShop: Where Inventors' Dreams Are Made

- Forget Crystal Balls: Let the Power of Math Inform Your Future

- Innovations: Ideas and Technologies of the Future

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus