Solar Power Technology Claims Misleading

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

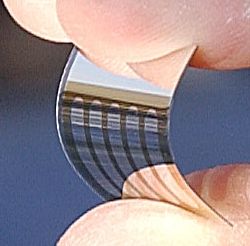

A new type of solar cell has recently gained attention as a possible cost-effective way to turn sunlight into electricity. Made from organic materials, the cells are cheaper and more flexible than currently used silicon-based solar cells.

But new information suggests organic solar cells may not work as well as advertised.

"There is a lot of press about breakthroughs that are basically unsubstantiated," said Keith Emery of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden, Colo.

In the November issue of Materials Today, an international review magazine, Emery and 20 other experts have signed a letter asking for more restraint in organic solar cell publicity. They think claims of "world record" performance must be independently verified.

Such independent evaluation is customary practice for all other solar cells, said Emery, who has done this sort of testing for 27 years.

"I have no interest in one solar cell technology over another," he told LiveScience. "But there needs to be a level playing field."

Organic market

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Organic solar cells are the new kids on the block. Because they are essentially plastic, they can be cheaply manufactured and even painted onto a surface.

Sunlight striking one of these cells creates separate positive and negative charges that can move through the material. The trouble that organics run into is that these charges often recombine before they can be corralled into a wire to generate a current.

Because of this, typical organic solar cells are only able to convert 3 percent of incoming sunlight into electricity. In comparison, most silicon-based solar cells have so-called efficiencies of around 12 percent.

But manufacturing silicon is not cheap. The current cost of electricity from silicon-based solar panels for houses or businesses is 25 cents to 40 cents per kilowatt-hour, roughly triple what most people pay their utility company.

Record breaking

Many researchers have, therefore, raced more recently to make more efficient organic solar cells with new materials or new combinations of materials. In the past few years, world record efficiencies as high as 6 percent have been publicized.

"They claim 6 percent, but we think it's 3 percent," Emery said.

He has looked through some of the reported data and found that it violates known physical laws. If reviewers aren't careful, he said, these exaggerated values could influence how funding is doled out.

"The trouble is that people think 6 percent is a good number for the state of the art, and it's not," Emery said.

Unreliable results can also set back researchers who may start working on new designs that seem promising but perhaps aren't.

Emery doesn't think this bad data is necessarily produced by willful researchers. In his experience there are a lot of pitfalls that can give faulty readings, especially on very small prototype cells. This is why he and others are asking that independent experts make the measurements.

Realistic goals

All the hype around organic solar cells gives the impression that the technology is more mature than it really is.

"The promise may be there," Emery said, "but it is still very much an emerging field."

It's often said that organic solar cells must reach 10 percent efficiencies to be viable. But Emery thinks there are possible applications at lower efficiencies.

Still, he sees organics making "slow incremental progress," probably staying below 1 percent of the solar cell market for the next 5 years. For further market penetration, organics will have to be better than existing products.

"The trouble is that silicon is a moving target; it keeps getting better and better," he said.

- Great Inventions: Quiz Yourself

- Top 10 Emerging Environmental Technologies

- Power of the Future: Top 10 Ways to Run the 21st Century

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus