Stem Cell Breakthrough Could Stifle Research

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Last week independent teams of scientists announced a major advance in stem cell research with their discovery of how to turn human skin cells into an "embryonic" state, enabling these cells to grow into nerve, heart or other types of human cells.

The method does not require the destruction of discarded human embryos from fertility clinics, currently the only source of embryonic stem cells. Thus, this would bypass the ethical concern that prompted the Bush White House to sharply limit funding on stem cell research.

Great news, maybe. Never has such a breakthrough been so worrisome to scientists. The discovery, albeit promising, might stifle stem cell research or send it down a dead-end path, for it is now harder than ever to secure funding to study the best source of embryonic stem cells—that is, embryos.

Turning back the clock

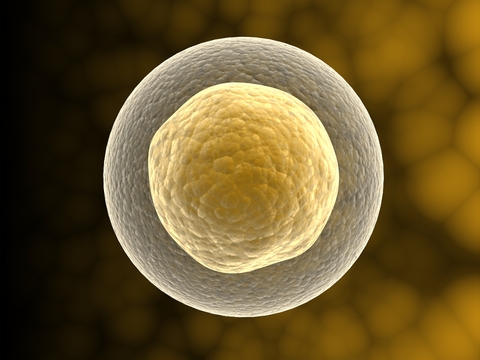

Embryonic stem cells come from an early-stage embryos called blastocytes. A blastocyte is a hollow ball of about 50 to 150 cells that forms a few days after fertilization in humans. These cells are pluripotent, meaning they can develop into any of the more than 200 types of human cells.

Soon after the blastocyte stage, the embryo attaches to the uterus and these cells divide and differentiate into specific cell types, such as those for the nervous system or immune system. Scientists are interested in embryonic stem cells because they could be used, in theory, to replace adult nerve or heart cells and cure spinal injuries or diseases.

Once a cell becomes specialized, it cannot return to the pluripotent stage... or so was the thinking a week ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Two teams—one led by Shinya Yamanaka of Kyoto University in Japan, the other by James Thomson of the University of Wisconsin—tricked skin cells into thinking they were embryonic. They did this by inserting into these cells four genes that are, apparently, part of the mechanism for making cells differentiate in the first place.

Mission accomplished?

The White House quickly took credit for inspiring this work with its strategy of not funding embryonic stem cell research for the past seven years. Some news media followed suit with headlines along the lines of "Stem Cell Debate Over."

This perception of one method trumping another is problematic, according to an op-ed in Cell, the journal that published Yamanaka's paper. "A big mistake now would be to consider human embryonic stem cells obsolete," wrote Holm Zaehres and Hans Scholer of Germany's Max Planck Institute for Molecular Biomedicine. "Embryonic stem cell research is more important than ever" because it has enabled Yamanaka's and Thomson's research.

The two teams weren't motivated by ethical reasons to look for an alternative method to produce pluripotent cells. Thomson, after all, is a pioneer of using human embryos and helped launch the research field in 1998. Rather, these scientists wanted a simpler approach, for human embryos are expensive and difficult to manipulate.

As a result of their discovery, lifting the ban on federal funding for embryonic stem cell research will be more challenging than ever, because politicians and the public who supports them are under the false belief that something better has come along. And it hasn't.

Cure causes cancer

The new method is preliminary and fraught with problems. Yamanaka first performed this technique on mice in 2006, and most of the mice developed cancer. This is because the special genes are carried into the cell by a virus, which can spread to other parts of the body and initiate rapid cell growth elsewhere.

Also, the faux-embryonic stem cells don't work as well at growing and expressing proteins as the real things. Maybe scientists will overcome these limitations. Without continued research on real embryonic stem cells, however, progress on the new method will be impossible.

The current federal funding freeze has already hurt U.S. research. Japan is basking in glory, and Yamanaka might win a Nobel Prize if the new technique works. America's Thomson essentially borrowed Yamanaka's technique, and his work has been supported largely with private funding.

A brave presidential candidate will see the new results in Cell and Science, connect that to a breakthrough announced two weeks ago in Nature on monkey embryonic stem cells, and then promise to increase funding for all kinds of embryonic stem cells to usher in an era of regenerative medicine.

- What is a Stem Cell?

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About You

- Medical Literacy: Read This or Die

Christopher Wanjek is the author of the books “Bad Medicine” and “Food At Work.” Got a question about Bad Medicine? Email Wanjek. If it’s really bad, he just might answer it in a future column. Bad Medicine appears each Tuesday on LiveScience.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus