Stem Cells May Be Secret to Regenerating Fingers and Toes

Mammals can regenerate the very tips of their fingers and toes after amputation, and now new research shows how stem cells in the nail play a role in that process.

A study in mice, detailed online today (June 12) in the journal Nature, reveals the chemical signal that triggers stem cells to develop into new nail tissue, and also attracts nerves that promote nail and bone regeneration.

The findings suggest nail stem cells could be used to develop new treatments for amputees, the researchers said. [Inside Life Science: Once Upon a Stem Cell]

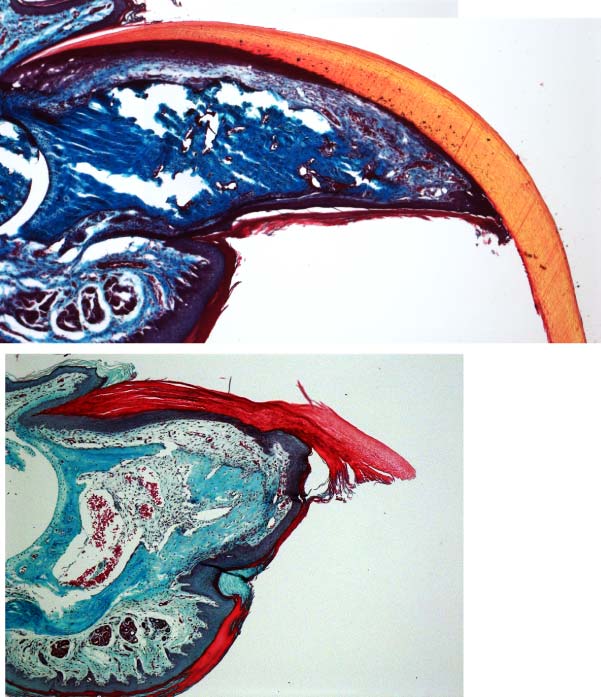

In mice and people, regenerating an amputated finger or toe involves regrowing the nail. But whether the amputated portion of the digit can regrow depends on exactly where the amputation occurs: If the stem cells beneath the nail are amputated along with the digit, no regrowth occurs, but if the stem cells remain, regrowth is possible.

To understand why these stem cells are crucial to regeneration, researchers turned to mice. The scientists conducted toe amputations in two groups of mice: one group of normal mice, and one group that was treated with a drug that made them unable to make the signals for new nail cells to develop.

They found that the signals that guided the stem cells' development into nail cells were vital to regenerating amputated digits. By five weeks after amputation, the normal mice had regenerated their toe and toenail. But the mice that lacked the nail signal failed to regrow either their nails or the toe bone itself, because the stem cells lacked the signals that promote nail-cell development. When the researchers replenished these signals, the toes regenerated successfully.

In another experiment, the researchers surgically removed nerves from the mice toes before amputating them. This significantly impaired nail-cell regeneration, similar to what happened to the mice that lacked the signals to produce new nails. Moreover, the nerve removal decreased the levels of certain proteins that promote tissue growth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Together, the results show that nail stem cells are critical for regrowing a lost digit in mice. If the same turns out to be true in humans, the findings could lead to better treatments for amputees.

Other animals, including amphibians, can also regenerate lost limbs. For example, aquatic salamanders can regrow complete limbs or even parts of their heart — a process that involves cells in their immune system. By studying these phenomena in other animals, it may be possible to enhance regenerative potential in people, the researchers said.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus