Animals Offer Clues to Regeneration

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

With the goal of finding ways to regenerate lost or injured body parts, researchers funded by the National Institutes of Health are exploring the strategies that some organisms use to regrow missing cells, organs and appendages. Here are a few examples.

Re-Forming From Stem Cells

Planarians are tiny freshwater flatworms — about the size of toenail clippings — that can re-form from slivers 1/300th of their original size. To do this, planarians use stem cells, called cNeoblasts, that have the ability to become almost any cell type in the body. Researchers at the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research studied the genes that are active in these stem cells to determine which of them are key players.

The researchers identified 10 “renewal” genes that help the stem cells create more like themselves. In addition, the scientists pinpointed two genes that trigger stem cells to become different types and also have roles in renewal. Because half of planarians’ genes have parallels in people, the scientists aim to use their findings to find regenerative genes in human embryonic stem cells.

Ringers in Regeneration

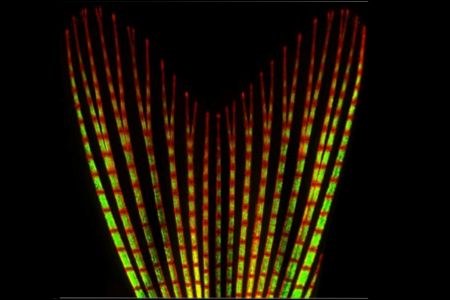

Zebrafish, blue-and-white-striped fish that grow to be about 1.5 inches long, can regrow fins. To study how, scientists at Duke University Medical Center generated zebrafish with depleted levels of cells responsible for creating bone. These cells, called osteoblasts, normally increase in number after a fish loses a fin. The researchers expected that when osteoblast-deficient fish lost fins, they wouldn’t be able to regenerate them as quicklyas those with normal levels of osteoblasts, if they could regenerate their fins at all. Surprisingly, all of the fish in the experiment regrew their fins, with recovery occurring at normal rates. Learning more about this process could aid the development of therapies for bone injury or loss in humans.

Sticking with the Same

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists at Washington University in St. Louis identified another zebrafish regeneration strategy by tracking how individual cells behaved in the stump of an amputated fin. One possibility was that adult nerve, bone and skin cells that make up the fin would revert into stem cells with the potential to become other cell types. However, this study showed that adult cells maintained their identities during regeneration, with skin cells in the stump only giving rise to skin cells in the new fin. This discovery suggests that inducing the cells that are already present to grow again could be an additional approach to replacing lost or injured tissues.

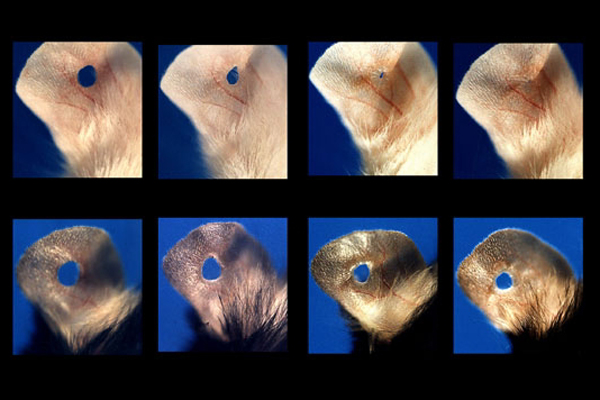

Gene Off, Healing On

Yet another technique for promoting regeneration might be found in turning genes off. Several years ago, researchers at The Wistar Institute discovered that inactivating a single gene allowed holes in mouse ears to close without scarring. The researchers determined that this breed of mice has an inactive version of a gene involved in regulating cell growth and division. The finding offers new insight into regeneration in a mammal and could guide the direction of future research.

While these results hold promise for the development of treatments to replace or repair human tissue, they also illustrate the complexity of regeneration and raise such questions as how organisms know what’s missing and how they prevent replacement tissues from cancerlike overgrowth.

This Inside Life Science article was provided to LiveScience in cooperation with the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, part of the National Institutes of Health.

Learn more:

Cool Video: Re-creating Kidney

Also in this series:

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus