Why Dead Authors Can Thrill Modern Readers

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

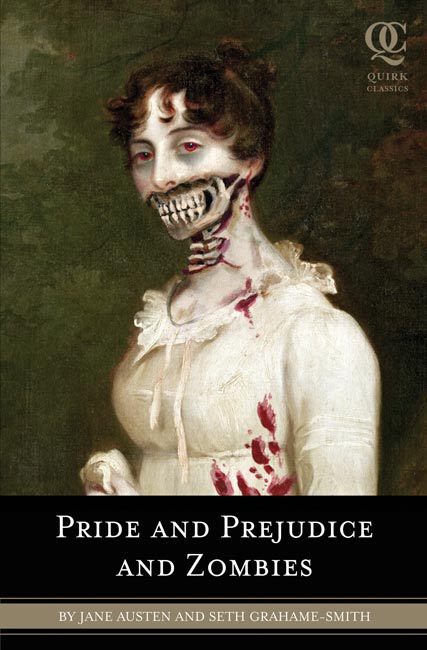

Classic stories still retain their storytelling power centuries later, and smart remakes do well to retain much of the original plot. That's the case in a new literary mash-up, "Pride and Prejudice and Zombies," where Elizabeth Bennett and Darcy take time away from courtship to hone their martial arts skills on the walking dead – a twist welcomed by both critics and "Janeite" fans of British author Jane Austen.

Such fascination with stories has compelled a small group of researchers to mine theories in evolutionary biology and psychology, in hopes of finding a connection between storytelling and the evolved human mind. Most agree that stories represent products of humanity's highly social existence, but debate rages over whether stories themselves may have evolved as an adaptation or social byproduct.

Their early findings could help explain why the best stories endure, and why remakes can find success despite seemingly retreading old ground. After all, Austen and other beloved storytellers may have found the sweet spot in tickling the social sensibilities of a modern mind not far removed from early Homo sapiens, let alone 19th-century British society.

Heroes and villains

Most people can easily identify the good guys and bad guys, or protagonists and antagonists, in well-known stories such as "Pride and Prejudice" or their spinoffs. But some researchers wanted evidence that the identification pattern holds true across many different stories.

"People use the terms protagonist and antagonist, but I'm not able to identify any essay or theoretical work that specifically focuses on protagonist and antagonist, major and minor characters," said Joseph Carroll, an English professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis.

Carroll helped found a movement known as Literary Darwinism, which looks at how stories reveal common evolutionary behaviors shared by all humans. His work has strong championing from evolutionary biologists such as E.O. Wilson at Harvard University.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In this case, Carroll hypothesized that modern readers would gravitate toward protagonists who displayed pro-social tendencies or promoted group cooperation — similar to how ancestral human hunter-gatherers valued such behavior.

He joined forces with another Literary Darwinist, Jonathan Gottschall, as well as two evolutionary psychologists on the study. Their online survey asked respondents to identify characters from classic 19th century British novels as protagonists, antagonists, or minor characters, and to rate character traits and emotional responses based on a psychological model of personality.

As predicted, people rated protagonists as displaying cooperative behavior that produced feel-good, positive responses from readers. They rated antagonists as being motivated by desire for social dominance, which drew negative emotional responses.

The study also found strong agreement among respondents rating character traits, even if just two people responded regarding a certain character. "Pride and Prejudice" had no lack of responses — 81 people showed a familiarity with heroine Elizabeth Bennett that might have made the Austen protagonist blush.

However, certain characters seemed to blur the line between protagonist and antagonist. Readers found plenty to dislike about characters such as Becky Sharp in "Vanity Fair" or Catherine and Heathcliff in "Wuthering Heights," but also empathized with the plight of those characters. "Such exceptions are extremely interesting but do not subvert the larger pattern," the study authors wrote.

Elizabeth's eventual love interest also stood out as a character that readers found interesting but also disagreeable. "He's sort of rude," Carroll said, describing Darcy as the kind of guy who walks into a room and immediately draws all eyes and gossip.

Darcy demonstrates this in his first "Pride and Prejudice and Zombies" appearance, when a ballroom crowd notices his haughty demeanor. He caps off his cold behavior by insulting Elizabeth within her hearing range, and she immediately decides to slit his throat with her ankle knife — before being interrupted by party-crashing zombies.

Pride and punishment

Another researcher says such exceptions show that the protagonist-antagonist setup is too simple to explain how Becky Sharp changes for the better, or how Heathcliff changes for the worse.

"They think that characters are either protagonists or antagonists pure and simple, and they don't see that the whole point about a Victorian novel, for example, is the extent to which characters change," said William Flesch, an English professor at the Brandeis University.

Flesch also draws on ideas from evolutionary biology, but disagrees with Literary Darwinist ideas in his book "Comeuppance: Costly Signaling, Altruistic Punishment, and Other Biological Components of Fiction." Instead of suggesting that readers like reading about fictional love and violence because of inherent interest in evolutionary dramas, Flesch said that stories play into our interest in socially monitoring other people — even unknown or imaginary people — to make sure that they are behaving pro-socially.

Social monitoring helps group survival by promoting social harmony and cooperation, Flesch suggested. That means seeing whether people are altruistically helping others through acts of justice and mercy, or cheating on their spouses, friends and society. Social monitoring also keeps track of whether people express the appropriate approval or disapproval of certain actions.

Studies have shown that some people may even go out of their way to punish the cheaters or defectors in a group, and earning the approval of others. These "altruistic punishers" pay a personal cost to punish but earn the social respect of others because that cost payment represents an altruistic signal.

Altruistic punishment doesn't just mean destroying the cheaters, though — it's a lesson to both the cheater and observers that such behavior cannot be tolerated. Ultimately, altruistic punishment means to change or convert the cheater's behavior.

"The reason we want conversion is because we can see that a lot of seemingly anti-social actions and attitudes are pro-social activities that aren't working right," Flesch told LiveScience. "We have a sense that they could work right, if they are rightly corrected or punished or changed."

Readers may delight in the complexity of "Pride and Prejudice" because wrong signals and social misunderstandings keep the potential lovers apart. Elizabeth wrongly punishes Darcy at one point by rejecting his marriage proposal (accompanied by a kick to the face in the mash-up), and yet he demonstrates his worthiness and evolutionary fitness by bearing the cost of her accusation that he is 'ungentlemanlike' with great patience.

"Now her punishment is misguided, based on false assumptions, it turns out, which is what makes it possible for Darcy to admire it without in the end being destroyed by it," Flesch pointed out. "And his altruism consists in his doing the right thing instead of demanding compensation for the ways he's been wronged."

Storytelling as adaptation

Given the complex social scenarios which good stories can deploy to tickle our brains, the Literary Darwinists and Flesch generally agree that storytelling itself encourages pro-social behavior.

"It's also probably true that — at least I hope it is — that there's something good about the kinds of practicing in empathy that we get out of stories, especially when they're subtle," Flesch noted. Tentative evidence exists in a 2006 study by Raymond Mar and other researchers at the University of Toronto, which found higher empathy scores in bookworms.

Carroll and other Literary Darwinists even suggest that storytelling could represent an evolutionary adaptation that promoted more social cohesion within early human groups.

"As far as we can tell, humans are the only species that create and occupy imaginative worlds, use it to regulate their behavior, activate their decision-making," Carroll said. "It has coevolved with human capacity for greater cognitive flexibility and for forming social groups."

That idea has powerful attraction for some evolutionary psychologists and humanities scholars, although others such as Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker have expressed skepticism. Flesch also remains dubious.

"I don't think [stories are] an adaptation: I think they're more a reflection of our intense pro-social disposition and they appeal to that disposition, which makes them particularly appropriate for social interaction," Flesch said.

Flesch added that the pro-social tendency could have evolved through more basic adaptations, such as costly signaling through altruistic punishment — or costly signaling through rewarding altruistic punishment.

That might explain why readers of "Pride and Prejudice and Zombies" can feel an ancient thrill upon reading of Elizabeth and Darcy bonding over their mutual warrior prowess, despite a tongue-in-cheek joke that ensues when Elizabeth gives back some ammunition with the query, "Your balls, Mr. Darcy?"

"They belong to you, Miss Bennett," Darcy replies.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus