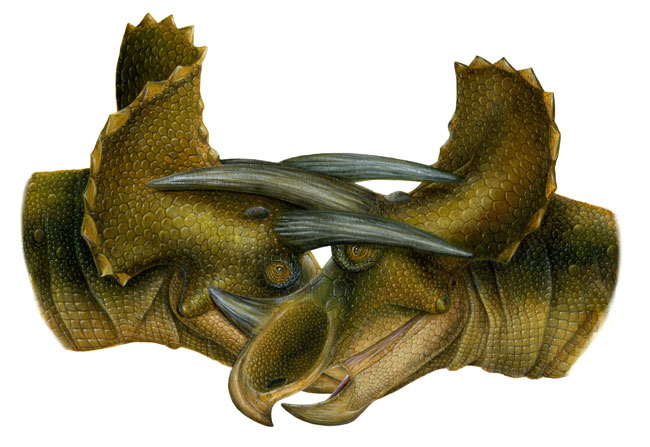

Triceratops Horns Used in Battle

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

About 100 million years ago, Triceratops likely engaged in horn-to-horn battles with its kin, according to a new analysis of the scrapes, bruises and healing fractures preserved on fossils of the dinosaurs' bony headgear.

"Paleontologists have debated the function of the bizarre skulls of horned dinosaurs for years now," said lead study researcher Andrew Farke, curator at the Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology in California. "Some speculated that the horns were for showing off to other dinosaurs, and others thought that the horns had to have been used in combat against other horned dinosaurs. Unfortunately, we can't just go and watch a Triceratops in the wild."

Past research has also suggested Triceratops' horns served as a means of communication and species recognition.

The results from Farke's new study point to combat as one usage.

"We're not suggesting Triceratops was using its horns only for fighting," Farke told LiveScience. "I like to think of the horns on these animals as kind of like the Swiss Army knives of the dinosaur world. They were using their horns for a variety of functions."

Horn patterns

Farke and his colleagues analyzed bone injuries from hundreds of fossils belonging to Triceratops and Centrosaurus.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Both dinosaurs belong to the family Ceratopsidae, but while Triceratops sported two long horns above its brows and a shorter one topping its beak-like snout, Centrosaurus had two smaller brow horns and a longer one on its nose. Both dinosaurs were equipped with a bony frill around their necks.

With such different horn patterns, the researchers assumed that if the dinosaurs were horn-butting with members of their own species the injuries of Triceratops and Centrosaurus should also be different from each other. But if they weren't poking and butting one another with those horns, the injuries should be relatively similar, perhaps due to random nicks from clumsily running into a tree or head butts from predators, Farke said.

Triceratops combat

The team found the so-called squamosal bone on the skull that forms part of the frill was injured 10 times more frequently in Triceratops compared with Centrosaurus. "The most likely culprit for all of the wounds on Triceratops frills was the horns of other Triceratops," Farke said. The combat would have been similar to that among modern antelopes and among deer.

Farke's previous research showed that if Triceratops were engaging in horn-to-horn combat with other Triceratops, the squamosal bone would be an area most frequently injured.

With Centrosaurus showing so few bony injuries, the researchers are unsure if this dinosaur fought with its horns.

"Possibly Centrosaurus wasn't using its horns for fighting, or if it was doing this, it was concentrating its energies on parts away from the skull, like maybe flank-butting or something like that," Farke said.

The study, detailed in the Jan. 28 issue of the online journal PLoS ONE, was funded in part by the National Science Foundation.

- Dino Quiz: Test Your Smarts

- Surprising Twists Found in Triceratops Horns

- A Brief History of Dinosaurs

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus