Ancient Squid-Like Creature's Last Meal Revealed

Millions of years ago, a squid-like creature called an ammonite died with the remains of its last meal wedged between its teeth. Now, new high-tech images reveal that meal — a mini-snail and three tiny crustaceans — and shed light on the diet of these once-common creatures.

"It gives us an insight because we never knew what these ammonites were eating," study researcher Neil Landman, a curator of paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, told LiveScience. "They were such a big part of the ocean biota… Now, for the first time, we think, 'Oh, we've got them. They're eating plankton in the water.'"

There's nothing in today's world quite like an ammonite. Like squid and octopus, ammonites were cephalopods, a type of mollusk, but that's about as far as the similarities go. They roamed the seas from 407 million to 65 million years ago, when they went extinct. Ammonite fossils are common, especially in South Dakota where Landman and his colleagues found their specimens.

Unlike today's squid and octopus, ammonites had external shells. Some species' shells were spirals, much like that of their closest-living look-alike, the nautilus. Other species had shells shaped like unicorn horns. It was one of these long-shelled groups, the baculites, that Landman and his colleagues examined.

Delicate specimens

Because baculite jaws are small and delicate, it's difficult to examine them without destroying the fossil specimen. Even if you were willing to slice up a specimen for examination, the process is likely to destroy the very structures you're trying to study, Landman said.

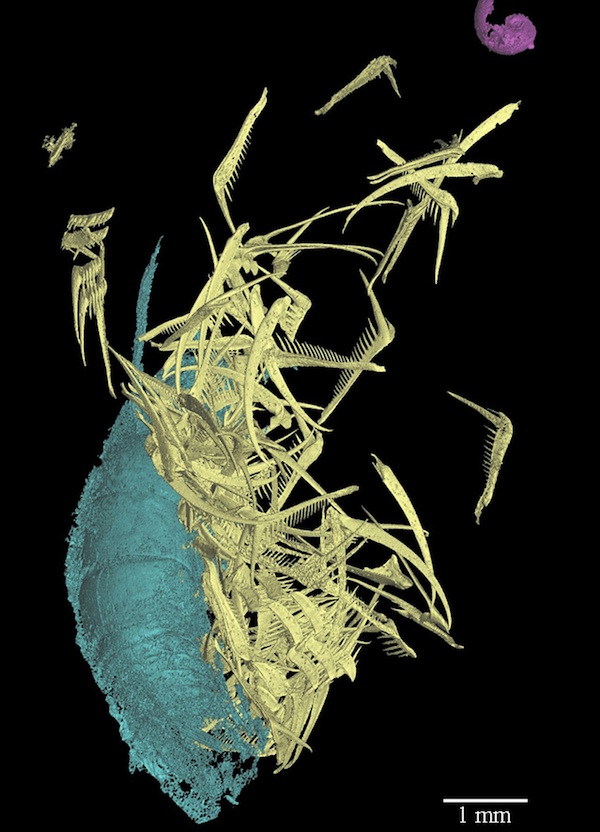

So the research team turned to a new technology, synchrotron X-ray microtomography. The technology is much like a very detailed CT scan. X-rays create virtual slices of the specimen, which are then stitched together into a three-dimensional image by computer software.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"You rely on all of this sophisticated software that puts all of these slices together and, my god, you're just astonished at what you see," Landman said.

In this case, the researchers saw a large lower jaw with thin teeth. Like many mollusks today, baculites had radula, or tongue-like structures covered with teeth like a comb. These structures stretch out like a conveyer belt to shepherd food to the esophagus, Landman said.

For ancient prey, the effect would have looked like something out of "20,000 Leagues Under the Sea," Landman said.

"If you were the size of a crustacean swimming in the water and you would see what looked to be a giant ammonite coming at you with a giant, beak-like jaw, you'd worry, I think," he said. "If you had the capacity for worry."

The last supper

One of the most amazing images revealed by the scans shows fragments of planktonic, or floating, crustacean stuck between the teeth of one of the ammonite fossils. The ammonite died with its last meal still in its mouth: Three crustacean pieces just a few millimeters in length and a tiny larval snail. [See a photo of an unfortunate crustacean]

That's fairly strong evidence that baculites were swimming in the water column snacking on plankton, said David Jacobs, a paleobiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. The find makes sense considering that the baculites' environment likely wouldn't have had much oxygen to support plant life on the bottom, Jacobs told LiveScience. It's also hard to imagine a 2-foot-long shelled animal shaped like an ice-cream cone chasing down large prey, he said.

"It really is a nice confirmation of what people might have thought but didn't have a lot of supporting evidence for," said Jacobs, who was not involved in the study.

The find also helps researchers better understand how ammonites fit into their ancient ecosystem. The question of what baculites ate has been a "hot debate," said Peter Harries, a paleontologist at the University of South Florida who was not involved in the study. The findings may not apply to other species of ammonites, he said, but they're important for understanding the ancient food web.

"It tells us a lot about the baculites, which during that time were extremely dominant," Harries told LiveScience. "So I think there it really has helped nail down their life habits."

Landman already has some theories about baculites' role in the circle of life. Baculites in the water column may have excreted fecal pellets (i.e., poop) that then fell to the ocean floor and provided snacks for bottom-feeders, he said. And the animals' habit of feeding on plankton may have spelled out their downfall during the catastrophe that killed off the non-avian dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

"Lots and lots of plankton became extinct at the time and, curiously, so did the ammonites," Landman said. "This is one of those 'aha' moments. Maybe the ammonites were relying on plankton as a food source, and when the plankton suffered … maybe this had a direct consequence on the ammonites."

The researchers detailed their findings Jan. 6 in the journal Science.

- 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts

- Mass Extinction Wiped Out Dinosaur Competitors

- Image Gallery: Drawing Dinosaurs

You can follow LiveScience Senior Writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus