What Killed King Tut

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

King Tut may have died in part from malaria and bone abnormalities, new mummy DNA analysis shows.

Tutankhamun, perhaps the most famous of the ancient Egyptian pharaohs, was part of the 18th dynasty of the Egyptian New Kingdom, which lasted from about 1550 to 1295 B.C. The boy king died in the ninth year of his reign, circa 1324 B.C., at the age of 19.

Because King Tut died so young, and left no heirs, there have been numerous speculations regarding diseases that may have occurred in his family, as well as debate regarding the cause of Tutankhamun’s early demise.

A new analysis of mummy DNA sought to find signs of any diseases — genetic or not — that could have contributed to King Tut's death. The DNA tests have also revealed or confirmed the likely identities and relationships of several previously unidentified mummies, including Tut's mother and father.

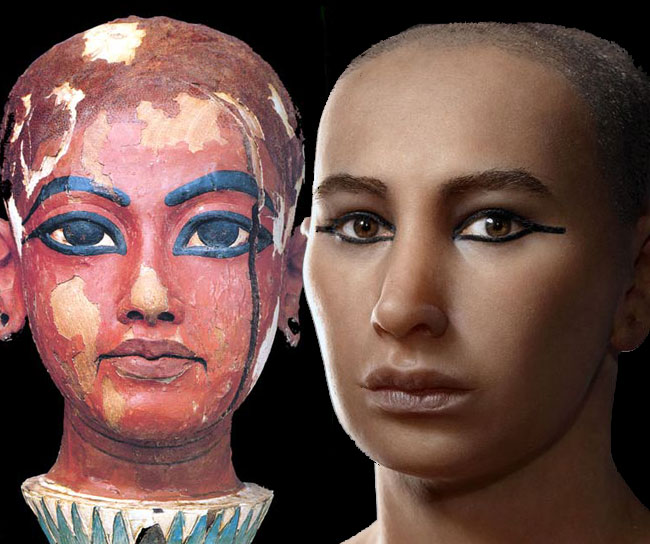

Artifacts have shown the royalty of that era as having a somewhat feminized or androgynous appearance. Diseases that have been suggested to explain this appearance include a form of gynecomastia (excessive development of the breasts in males, usually the result of a hormonal imbalance), Marfan syndrome and others. (People with Marfan syndrome typically have abnormally long limbs and long, thin fingers and can have serious heart abnormalities.)

"However, most of the disease diagnoses are hypotheses derived by observing and interpreting artifacts and not by evaluating the mummified remains of royal individuals apart from these artifacts," the researchers who conducted the analysis noted.

Zahi Hawass, head of the Supreme Council of Antiquities in Cairo, Egypt, and colleagues conducted a study to determine familial relationships among 11 royal mummies of the New Kingdom, and to search for pathological features attributable to inherited disorders, infectious diseases and blood relationship.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They also examined for specific evidence regarding Tutankhamun's death, with some scholars having hypothesized that it was attributable to an injury; septicemia (bloodstream infection) or fat embolism (release of fat into an artery) secondary to a femur fracture; murder by a blow to the back of the head; or poisoning.

From September 2007 to October 2009, royal mummies underwent detailed anthropological, radiological, and genetic studies. DNA was extracted from two to four different biopsies per mummy.

No signs of gynecomastia or Marfan syndrome were found in the mummies that were examined.

"Therefore, the particular artistic presentation of persons in the Amarna period is confirmed as a royally decreed style most probably related to the religious reforms of Akhenaten [suspected to be Tut's father]," the authors said. "It is unlikely that either Tutankhamun or Akhenaten actually displayed a significantly bizarre or feminine physique. It is important to note that ancient Egyptian kings typically had themselves and their families represented in an idealized fashion."

But, the researchers did find an accumulation of malformations in Tutankhamun's family.

"Several pathologies including Kohler disease II [a bone disorder] were diagnosed in Tutankhamun; none alone would have caused death," the authors noted.

Genes that are specific to the parasite that causes malaria were also found in four mummies, including Tut's. The genetic results suggest that a malaria infection in conjunction with a condition in which poor blood supply to the bone leads to weakening or destruction of an area of bone killed the Egyptian king.

"Walking impairment and malarial disease sustained by Tutankhamun is supported by the discovery of canes and an afterlife pharmacy in his tomb," the authors said.

They added that a sudden leg fracture, possibly from a fall, might have resulted in a life-threatening condition when a malaria infection occurred.

The new findings are detailed in the Feb. 17 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

- Heart Disease Found in Ancient Mummies

- Images: Amazing Egyptian Discoveries

- More About Mummies

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus