Kilimanjaro Ice Fields Set to Disappear

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

After holding firm for thousands of years, shrinking ice fields atop Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania are dramatically depleted compared to just 100 years ago, a new study finds.

The ice fields could be completely gone within two decades and perhaps even sooner, researchers said.

The findings, by paleoclimatologist Lonnie Thompson at Ohio State University and co-authors, indicate that a major cause of this ice loss is likely to be the rise in global temperatures.

Separate research in 2007 suggested the meltoff at Kilimanjaro was not primarily due to global warming. But Thompson and colleagues say that their new, comprehensive research indicates that although changes in cloudiness and precipitation may also play a role, they appear less important than global warming, particularly in recent decades.

"The loss of Mount Kilimanjaro's ice cover has attracted worldwide attention because of its impact on regional water resources," said David Verardo, director of NSF's Paleoclimate Program, which funded the research along with Ohio State University's Climate, Water and Carbon Program. "The remaining ice fields are melting from all sides," said Verardo. "Like many glaciers in mid-to-low latitudes, Kilimanjaro's may only be with us for a short time longer."

This first calculation of ice volume loss indicates that from 2000 to 2007, the loss by thinning is now roughly equal to that by shrinking, according to a statement from the researchers.

Among the findings published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences:

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

- 85 percent of the ice that covered the mountain in 1912 had been lost by 2007, and 26 percent of the ice there in 2000 is now gone.

- A radioactive signal marking the 1951-52 "Ivy" atomic tests that was detected in 2000 some 1.6 meters (5.25 feet) below the surface of the Kilimanjaro ice is now lost, with an estimated 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) missing from the tops of the current ice fields.

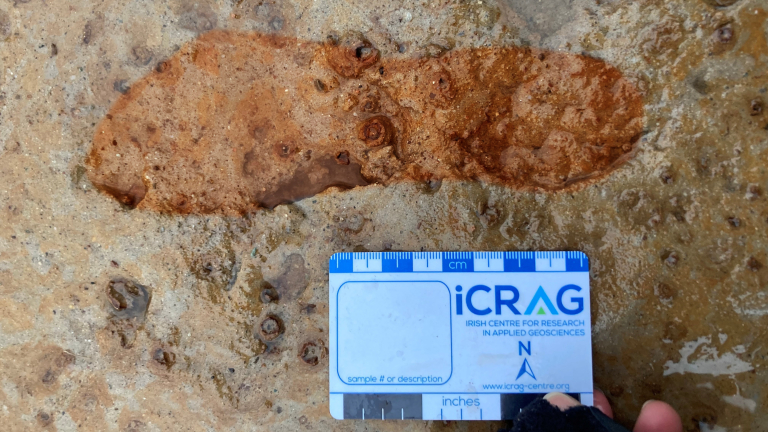

- The presence of elongated bubbles trapped in the frozen ice at the top of one of the cores shows that surface ice has melted and refrozen. There is no evidence of sustained melting anywhere in the rest of the core material which dates back 11,700 years.

- Even 4,200 years ago, a drought in this part of Africa that lasted about 300 years and left a thick (about 1-inch) dust layer, was not accompanied by any evidence of melting.

These observations confirm that the current climate conditions at Mount Kilimanjaro are unique over the last 11 millennia.

"This is the first time researchers have calculated the volume of ice lost from the mountain's ice fields," said Thompson, a scientist at Ohio State's Byrd Polar Research Center. "If you look at the percentage of volume lost since 2000 versus the percentage of area lost as the ice fields shrink, the numbers are very close."

While the loss of mountain glaciers is most apparent from the retreat of their margins, Thompson said an equally troubling effect is the thinning of the ice fields from the surface.

The summits of both the Northern and Southern Ice Fields atop Kilimanjaro have thinned by 6.2 feet (1.9 meters) and 16.7 feet (5.1 meters), respectively. The smaller Furtwangler Glacier, which was melting and water-saturated in 2000 when it was drilled for samples, has thinned as much as 50 percent between 2000 and 2009.

"It has lost half of its thickness," Thompson said. "In the future, there will be a year when Furtwängler is present and by the next year, it will have disappeared."

Thompson said the changes occurring on Mount Kilimanjaro mirror those on Mount Kenya and the Rwenzori Mountains in Africa, as well as tropical glaciers high in the South American Andes and in the Himalayas.

"The fact that so many glaciers throughout the tropics and subtropics are showing similar responses suggests an underlying common cause," he said.

"The increase of Earth's near-surface temperatures, coupled with even greater such increases in the mid- to upper-tropical troposphere, as documented in recent decades, would at least partially explain the observed widespread similarity in glacier behavior."

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus