Remains of Mini 'Komodo Dragon' Found in Greece

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A long-lost relative of today's Komodo dragons lived in Europe as recently as 800,000 years ago.

These reptilians were much smaller than the predatory Komodo dragons that live today in Indonesia. But the discovery of their fossils at a site in Greece was a surprise, because monitor lizards were thought to have vanished in Europe around 2.5 million years ago as climate conditions gradually changed.

"It's a survivor, let's say," said Georgios Georgalis, a doctoral candidate in paleontology at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland and the University of Torino in Italy. [In Photos: Rare Birth of 'Baby Dragons' at Slovenia Cave]

Persistant lizard

Monitor lizards are a big group. Scientifically, they're known as "varanids," and at least 70 species live today in Africa, Australia and Asia. The most famous species, the Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis), can grow to nearly 10 feet (3 meters) long.

Monitor lizards used to roam Europe, too, but they seem to vanish from the fossil record by the time of the Pliocene (5 million to 2.6 million years ago), when the climate took a turn for the cool and dry. The new specimen from near Athens is much more recent than that, dating back less than a million years.

"We [now] know that varanids survived at least until the middle Pleistocene," Georgalis told Live Science.

The new monitor lizard is known from only a few pieces of skull and jaw. Fortunately, Georgalis said, these specimens are a good basis for identifying varanids, because teeth and jaws vary widely between lizard species.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Miniature monitor

The fossil was found almost 30 years ago at a site called Tourkobounia outside Athens, Georgalis said. He discovered it in a collection on loan to the University of Torino.

"I was very, very surprised, happily surprised, when I saw this material, because it was highly distinctive," Georgalis said.

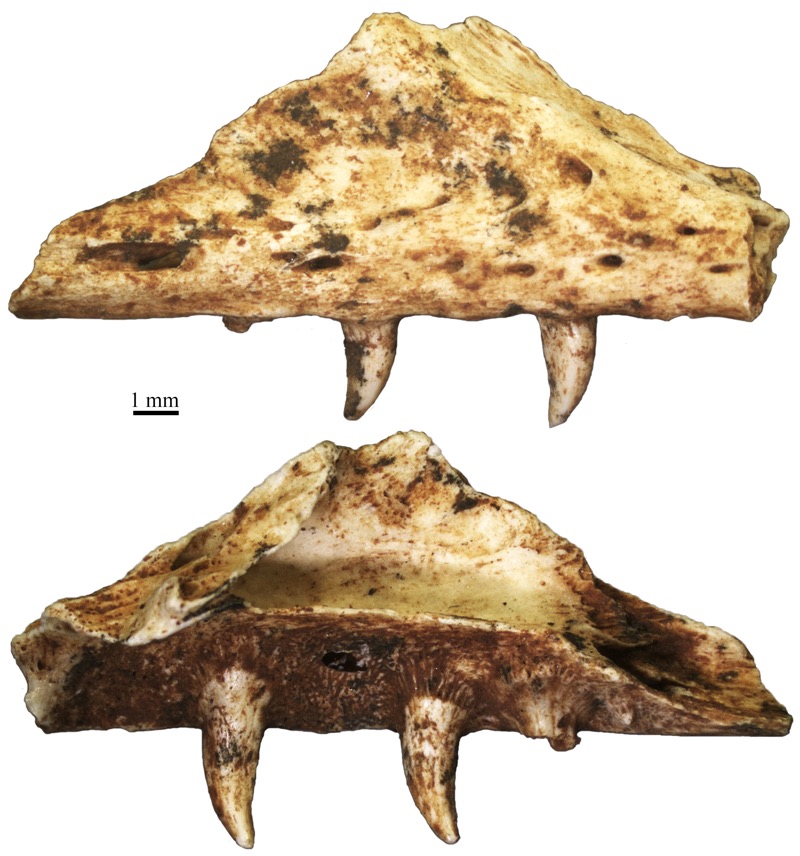

The biggest piece of bone is the right maxilla, or upper jaw, at just 0.7 inches (17 millimeters) long. Attached are two pointy teeth, which are only about 0.15 inches (4 mm) long. The second portion of the fossil is a piece of the lower jaw 0.6 inches (15.7 mm) long. One other tooth was detached from the jawbones.

Based on the anatomy, this monitor lizard was likely related to monitor lizards that had called Europe home in the Miocene, 23 million to 5 million years ago, when varanids were common on the continent. It was probably a relic of those old populations, Georgalis said, confined to the southeastern edge of Europe where the weather was still warm enough to support it.

Perhaps for that reason, the lizard was puny compared with today's Komodo dragons — much smaller than a comparable ancient European monitor lizard that measured 2 feet (60 centimeters) long, not counting its tail, Georgalis and his colleagues wrote May 12 in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. The lizard was also smaller than earlier European monitor lizards, Georgalis said, and the size reduction may have been an adaptation for surviving in a cooler climate. Alternatively, the fossil may simply have been a baby.

Georgalis and his team are now hoping to find other varanids from Pleistocene Greece.

"We're trying to understand when is their extinction date, and why they became extinct from Europe," he said.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus