Human-Caused Climate Change Made 2016 Way Too Hot

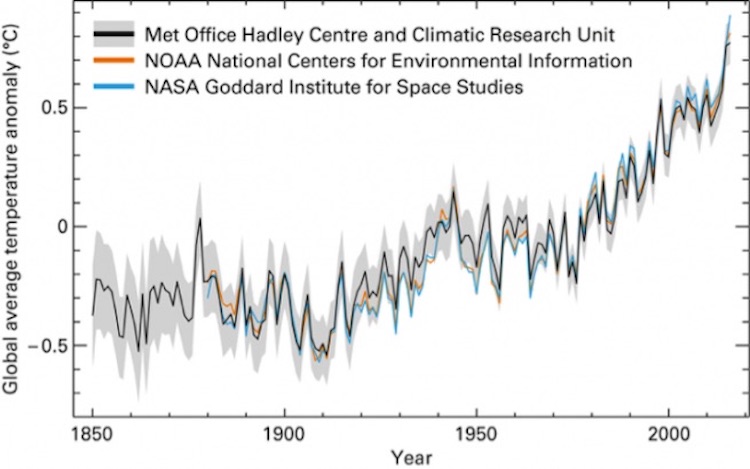

The year 2016 was one for the record books, at least when it comes to the weather. Last year had the highest global temperature in modern history and extremely high levels of carbon dioxide and sea level rise, as well as exceptionally low levels of Arctic sea ice, according to the United Nation's World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

These alarming weather events and trends are continuing into 2017, the WMO said in a report released Tuesday (March 21).

The report — part of the WMO's annual State of the Global Climate — pulled data from multiple international datasets that are independently maintained. In addition, for the first time in its more than 20-year history of issuing these statements, the WMO partnered with other United Nations branches to include data on social and economic impacts of climate change. [The Year in Climate Change: 2016's Most Depressing Stories]

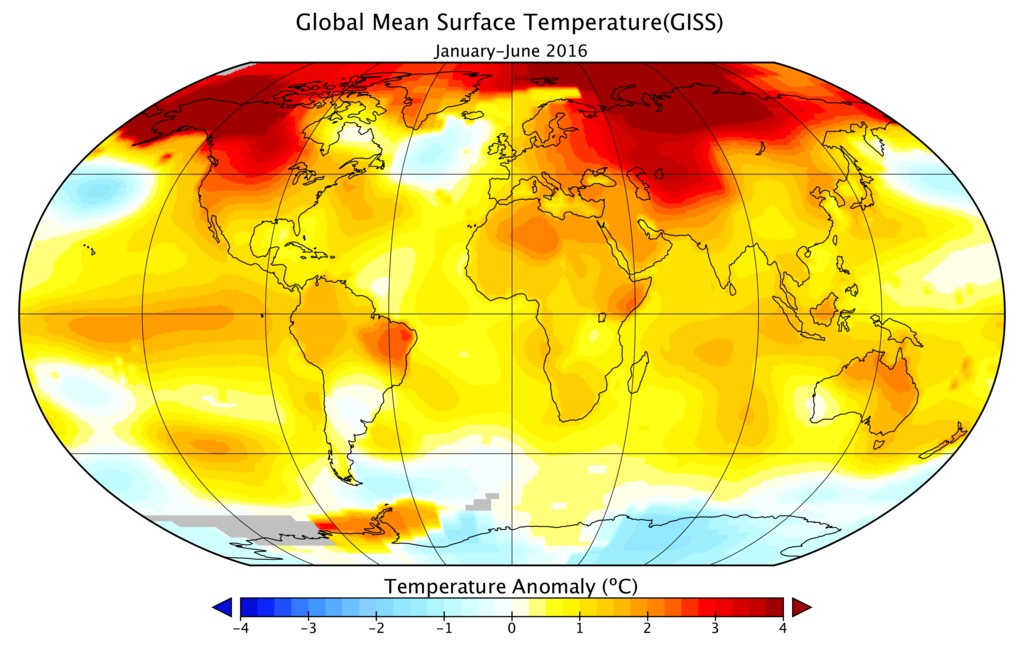

"This report confirms that the year 2016 was the warmest on record — a remarkable 1.1 degrees Celsius [1.98 degrees Fahrenheit] above the pre-industrial period, which is 0.06 C [0.1 F] above the previous record set in 2015," Petteri Taalas, the WMO secretary-general, said in a statement. "This increase in global temperature is consistent with other changes occurring in the climate system."

For instance, globally averaged sea-surface temperatures also experienced record-breaking highs, Taalas said.

"With levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere consistently breaking new records, the influence of human activities on the climate system has become more and more evident," Taalas said. Scientists are able to connect these high temperatures and some extreme weather events to man-made climate change by using long-term climate data and high-powered computing tools, he added.

Some of 2016's extreme weather events include severe droughts that caused food insecurity among millions of people in southern and eastern Africa and Central America; Hurricane Matthew, which carved a destructive trail through Haiti in October 2016 and was the first Category 4 storm to make landfall there since 1963; and heavy rains and floods in eastern and southern Asia, according to the WMO.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mercury rising

Each of the 16 years since 2001 has been at least 0.72 F (0.4 C) warmer than the long-term average for the 1961-1990 base period, the WMO said. Every decade, temperatures have warmed 0.18 F to 0.36 F (0.1 to 0.2 C), the organization added.

The El Niño of 2015 and 2016 explains, in part, why 2016 was so hot. On top of warming long-term climate change temperatures, the weather is usually warmer during strong El Niño years, including 1973, 1983 and 1998 — years that had temperatures between 0.18 F and 0.36 F warmer than background levels.

During El Niño periods, warm water in the western tropical Pacific Ocean flows eastward toward South America, and heats surface waters off the coast of northwestern South America. These warm waters evaporate easily, and can fuel Pacific hurricanes and other unusual weather events. The temperatures of 2016 were consistent with this pattern, the WMO said.

Sea levels worldwide also rose so much during the recent El Niño event that early 2016 levels broke record highs. Meanwhile, global sea ice cover recededmore than 1.5 million square miles (4 million square kilometers) below average in November.

Higher ocean temperatures have contributed to coral bleaching and mortality, even in tropical waters. When coral die, the entire marine food chain is harmed, the WMO said.

In addition, atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) levels reached 400 parts per million (ppm) in 2015, the WMO said. That figure means there were 400 molecules of carbon dioxide in the air per every million air molecules. The 400 ppm threshold is high in contrast with the past 800,000 years, when CO2 levels fluctuated between about 170 ppm and 280 ppm, Michael Sandstrom, a doctoral student in paleoclimate at Columbia University in New York City, previously told Live Science.

The Paris Agreement, a U.N. climate treaty, addresses how to countries can decrease their emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. The agreement is vital as it encourages the world to tackle "climate change by curbing greenhouse gases, fostering climate resilience and mainstreaming climate adaptation into national development policies," Taalas said. [Earth in the Balance: 7 Crucial Tipping Points]

2017 trends

Not everything made it into the 2016 report. New studies show that the ocean heat content may have increased more than previously thought, and early data suggests that there is no easing in the rate of increase for atmospheric CO2 concentrations, the WMO said.

"Even without a strong El Niño in 2017, we are seeing other remarkable changes across the planet that are challenging the limits of our understanding of the climate system," David Carlson, the World Climate Research program director, said in the statement. "We are now in truly uncharted territory."

For instance, the Arctic has had three "polar heat waves" this winter, Carlson said. These heat waves are alarming because sea ice, which usually refreezes during Arctic winters, is already at record lows compared with the past few years, he said.

What's more, changes in the Arctic and melting sea ice are causing a shift in wider oceanic and atmospheric circulation patterns, the WMO said. These changes are affecting the jet stream, the fast-moving band of air that regulates worldwide temperatures, and are already influencing weather patterns around the planet, the WMO said.

For example, parts of Canada and the United States were unusually balmy this year, while other regions, including the Arabian Peninsula and northern Africa, were unseasonably cold in early 2017.

In South Africa, the city of Pretoria sizzled at 108.8 F (42.7 C) and Johannesburg reached 102 F (38.9 C) on Jan. 7 — temperatures that were at least 5.4 F (3 C) higher than previous all-time records for those sites, the WMO said.

In February, the United States broke or tied more than 11,700 warm temperature records, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said. Down Under, where the seasons are flipped, parts of Australia had prolonged and extreme heat in January and February, and broke many new temperature records, the WMO said.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus