What's Up with Warm February Weather in Most of US?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

It may still be February, but spring-like temperatures in most of the United States are making people shed their winter coats unseasonably soon. So what's behind this warm weather?

Typically, February is the third coldest month of the year, falling behind December and January, but this February may be one for the record books, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI).

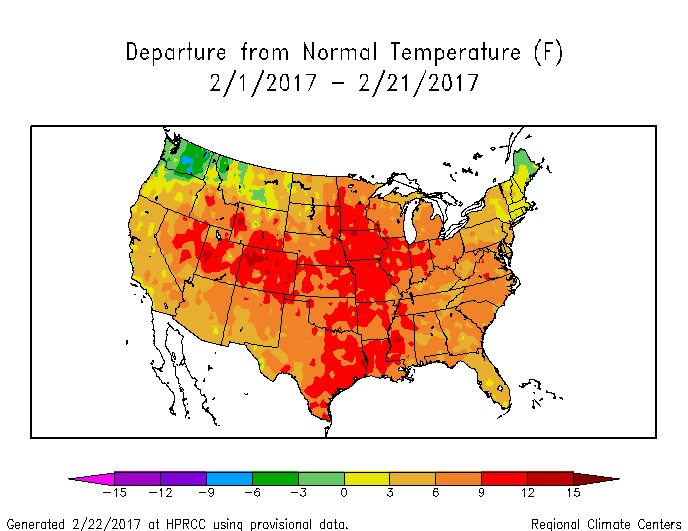

The official average temperature isn't available for February 2017 (since the month isn't over yet), but the first three weeks in most U.S. locations were warmer than average, except for in the Pacific Northwest and northern New England, said Jake Crouch, an NCEI climate scientist in Ashville, North Carolina. [The 7 Harshest Environments on Earth]

It's so unseasonably warm, that 5,294 daily high-temperature records were broken across the country from Feb. 1 through Feb. 20, Crouch said. In contrast, there were just 85 low-temperature records broken during that same period, making it a ratio of 62:1 of high versus low new daily- temperature records, he said.

"For every cold daily-temperature record we've broken in February, we've broken 62 warm daily-temperature records," Crouch told Live Science. "That ratio is very high. In a normal situation, we would expect those to be a 1-to-1 ratio."

That ratio may go even higher as the month draws to an end, according to forecasts from the Climate Prediction Center, Crouch said.

Why it's warm

Climate scientists are still collecting and crunching data, so it's unclear why it's so warm this February, Crouch said. However, the absence of a wandering polar vortex may partly explain the early spring-like weather. In past years the Arctic's polar vortex — a low-pressure system that spins frigid air counterclockwise around the North Pole — has ventured beyond its northerly home into the United States, lowering temperatures.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The mechanism beyond the polar vortex has natural variability, and this year it appears to be leaving the continental United States alone, but affecting northern Russia and northern Europe, which have been "fairly cold this winter season," Crouch said.

Meanwhile, the West Coast has been seeing an onslaught of rainstorms coming in from the Pacific Ocean. As these rain clouds move west, they've been dumping snow on some states west of the Rocky Mountains, which have seen more snow than usual this February, Crouch said.

There has been less snow east of the Rocky Mountains, except for the Northeast, an area that has seen more snow than usual, though it's not yet clear why, he said. [Fishy Rain to Fire Whirlwinds: The World's Weirdest Weather]

Alarming trend

February is growing warmer faster than the other months, according to the NCEI. Based on temperature data from 1895 to 2016, February is warming at a rate of 3.1 degrees Fahrenheit (1.7 degrees Celsius) per century. The runner-up, March, is warming at a rate of 2.5 F (1.3 C) per century, and the month with the slowest warming rate is September, at 0.8 F (0.4 C) per century. None of the months are cooling down over time, the NCEI reported.

"That warming rate doesn't include this February," Crouch said. "This February is going to be really warm, most likely, once we have the data for the entire month. So that rate might also increase once we have the February 2017 data."

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus